Property rights are a universal right enshrined in the US Constitution and the United Nations Charter. Indeed, it is in search of just such rights that many of the world’s poor are motivated to cross borders into countries like the US.

For those living in the richest parts of the world, it is easy to take clear property rights for granted. But the reality is that only 2.3 billion people have the documents to protect and leverage their rights – including approximately one billion people living in Japan, Singapore, and the democratic West, and another billion in certain developing countries and former Soviet states.

Documentation is not just a bureaucratic stamp on a piece of paper. It is crucial to economic progress and inclusion. The reason the undocumented have an interest in being properly documented – whether they know it or not – is that clear property rights provide their owners and the things they own with a lot of additional value.

In the US or Europe, for example, a house not only serves as a shelter; it is also an address that can identify people for commercial, judicial, or civic purposes, and a reliable terminal for services, such as energy, water, sewage, or telephone lines. Documentation also allows assets to be used as financial instruments, providing their owners with access to credit and capital. If you want to take out a loan – whether you are a mining company in Colorado or a Greek shoemaker in New York – you must first pledge documented property in one form or another as a guarantee.

As I have shown elsewhere, the poor of the world are in possession of some $18 trillion of undocumented assets in real estate alone. But those assets will never attain their full value if they are not documented. As it stands, they cannot be used to raise capital. Nor can they be joined with other assets to create more complex and valuable holdings.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Quote of the day: Property Rights Provide Their Owners And The Things They Own With a Lot of Additional Value

Monday, October 14, 2013

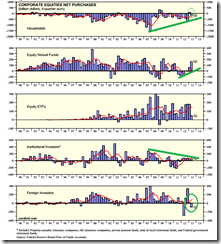

Phisix: Rising Systemic Debt Erodes the Margin of Safety

Investment requires and presupposes a margin of safety to protect against adverse developments. In market trading, as in most other forms of speculation, there is no real margin for error; you are either right or wrong, and if wrong lose money. Consequently, even if we believed that the ordinary intelligent reader could learn to make money by trading in the market, we should send him elsewhere for instruction. But everybody knows that most people who trade in the market lose money at in the end. The people who persist in trying it are either (a) unintelligent, or (b) willing to lose money for the fun of the game, or (c) gifted with some uncommon and incommunicable talent. In any case they are not investors.

In their calmer moments, investors recognize their inability to know what the future holds. In moments of extreme panic or enthusiasm, however, they become remarkably bold in their predictions; they act as though uncertainty has vanished and the outcome is beyond doubt. Reality is abruptly transformed into that hypothetical future where the outcome is known. These are rare occasions, but they are also unforgettable: major tops and bottoms in markets are defined by this switch from doubt to certainty

The first and most obvious of these principles is, “Know what ou doing—know your business.” For the investor this means: Do not try to make “business profits” out of securities—that is, returns in excess of normal and dividend income—unless you know as much about security values as would need to know about the value of merchandise that you proposed to deal or manufacture

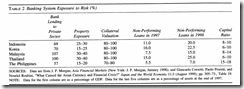

It is also important to note that indebtedness in the Philippines is still quite low. Domestic credit-to-GDP ratio at 50.4% (Q4 2012) still ranks one of the lowest in the region, This would suggest that the risk of excessive leverage is less and the threat to financial stability is likewise lower, should asset prices correct.

Economies may be especially vulnerable to the extent that they have significant external financing requirements, saw rapid credit growth when interest rates were low, or have experienced large increases in debt. Indeed, markets appear to be discriminating on the basis of country fundamentals. Indonesia’s high bond yields partly reflect its current-account deficit. Again, in Indonesia, and in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, there are concerns about rapid credit growth leading to financial-sector overextension. Gross national debt now exceeds 150 percent of GDP in Malaysia, China, and Thailand, and 100 percent of GDP in the Philippines (Figure 29; see also note on “China’s Credit Binge May Have Run Its Course,” in this Economic Update). Specific concerns include a sharp increase over the last few years in household debt in Malaysia and Thailand, and high leverage in state-owned enterprises in Vietnam.

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

P-Noy’s Entourage is a Showcase of the Philippine Political Economy

“As a society, culturally we get what we celebrate”, that’s how prolific Forbes nanotech analyst-writer Josh Wolfe describes the importance of role models in shaping society.

Who we celebrate essentially reflects on our actions. For instance, if we worship politicians and celebrities, we tend to follow their actions. Our time orientation would narrow to match with theirs.

And having a short term time preference means we value today more than the future, thus we would be predisposed to indulge in gambling, hedonistic (high risk but self gratifying) activities and political actions that would dovetail with such values.

However, if we see entrepreneurs or scientists as our role models then we are likely to value the future more than today. We would learn of the essence of savings, capital accumulation and trade.

What has this got to do with P-Noy’s trip to China? A lot.

President Aquino’s entourage simply is a showcase of how the Philippine political economy works.

From today’s Inquirer

Underlining the trade and investment slant of his state visit to China, President Benigno Aquino III arrived here with a 270-strong business delegation, including the Philippines’ top industry leaders.

It is the biggest business contingent of Mr. Aquino’s foreign trips.

And for what stated reason? Newswires say this is meant to secure $60 billion worth of investments.

According to Bloomberg,

The Philippines may secure as much as $60 billion in Chinese investments under a five-year plan to be signed during Aquino’s stay, Christine Ortega, assistant secretary for foreign affairs, told reporters in Manila on Aug. 24. This trip alone may bring $7 billion in commitments, Trade Undersecretary Cristino Panlilio told reporters in Beijing yesterday…

Aquino is counting on investments to boost economic growth that slowed for a fourth straight quarter. Gross domestic product increased 3.4 percent in the three months through June from a year earlier, from a revised 4.6 percent in the first quarter, the National Statistical Coordination Board said today.

Lagging Investments

Net foreign direct investment in the Philippines fell 13 percent to $1.7 billion in 2010 from a year earlier, the central bank said in March. Between 1970 to 2009, the country lured $32.3 billion in FDI, compared with $104.1 billion for Thailand, according to United Nations data.

Higher returns on investments will come from resources “that have been untapped for such a long time,” Aquino said in an Aug. 18 interview, citing plans to explore for energy in the South China Sea. Two of 15 blocks put out for tender in June are in waters China claims.

The Philippines plans to boost hydrocarbon reserves by 40 percent in the next two decades. Mineral fuels accounted for 17 percent of total monthly imports on average last year, from 11 percent in 2000, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“We want to resolve the conflicting claims so that we can have our own gas,” Aquino said Aug. 29. “Once we have our own, we will not be affected by events in other parts of the world.”

First of all it isn’t true that the Philippines have little access to $60 billion worth of funds for investment.

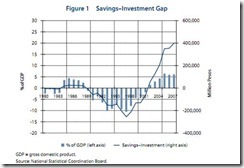

In fact, the Philippines has a disproportion of savings to investment as shown below.

National savings alone is almost enough to bankroll these required investments (charts above and below from ADB)

Yet this doesn’t even count other domestic assets which can be used as collateral or as alternative sources for funding.

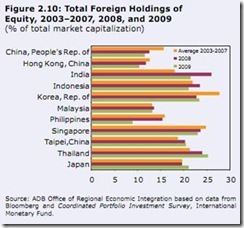

The Philippine Equity markets had a market cap of $202 billion as of the last trading day of 2010.

Foreigners hold around 20% of the market cap; even assuming 50% foreign ownership that’s still $100 billion worth of potential collateral.

And we also have the corporate bond markets (4.1% of GDP) and vast property assets which because of the lack of secured property rights, around 67% of rural residents in the Philippines live in housing that is considered as ‘dead capital’ which is worth about $133 billion Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto estimated in 2001 in his book, the Mystery of Capital

In other words, many of the big shot investors who went with P-Noy do not see sufficient returns on their investments, hence have been reluctant to deploy their savings on local investments.

They instead went with the President to supposedly seek out “partners” to 'spread the risks'.

On the other hand, these business honchos will likely use this opportunity to invest overseas!

Why then the lack of domestic investments?

Aside from the lack or insufficient protection of property rights, a very important hurdle to investments is simply the inhospitable environment for investors.

As the table above shows, the Philippine economy has been strangled or choked by politics.

So bringing in a high powered presidential entourage won’t help unless there would be dramatic structural reforms on our political institutions that would encourage profitable investments.

Most of the deals that would be obtained from this trip will likely be political privileges or concessions (most possibly backed by implicit guarantees from the Philippine government).

This brings us to the significance of role models.

Essentially, P-Noy sees big business as the main way to entice investments or reinvigorate the economy, hence this star-studded retinue (could this be a junket??)

Why leave out the public, when I would presuppose that much of the investable savings are held by them? Is it because that, as his political supporters, this would serve as the ripe opportunity to be rewarded (with state induced deals)?

Or is this authorative show of force simply been about showmanship? (Public choice theory is right again showing how politicians are attracted to symbolisms to promote their self interests)

Bottom line: P-Noy’s China trip reveals of the essence of the Philippine political economy; economic opportunities allocated or provided for by the state.

In short, state or crony capitalism.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Hernando De Soto: Unclear Property Rights And Complex Rules Led To Market Crashes

On the rule of law...

"when it comes to property rights: most of the world is still in the 19th century. During that time period, the US put all their property information on paper. These "rule of law" standards identified who owned what property - this system is still viable today...

"when independence, solidarity and individuality function under the "Rule of Law, all players are on the same playing field; that is the rules apply the same to all [but note, this concept is non-existent in many parts of the world]. South American and African nations borrowed their laws from their colonizers. In contrast, anarchy has many laws within the same territory.

my comment: In an earlier post Are People Inherently Nihilistic?, we said that the term "anarchy" comes with different references. Here, Mr. De Soto appears to imply that anarchy (or perhaps defined as market turmoil) was caused by the many intricate laws within the same territory, which brings us to the next topic...

De Soto's view on property rights and rule of law's role in today's market crash...

``The basic problem with the financial meltdown today is that with all the convoluted derivatives, trades, bundling, etc. the US does not know where its financial paper is. Thus, the US cannot define who is solvent and who is not. The "Rule of Law" comes into play because property ownership is based on a paper trail. Since the paper trail is incomplete regarding detailed ownership of the property underlying the complex derivatives that were sold in the financial industry, no one knows who owns exactly what and what it is worth. As a result, trust plummets."

my comment: so the questionable application of the "rules" which has led to the ambiguous stance on ownership rights has prompted for a lost of trust or "anarchy".

Besides, excess and poorly defined regulations have prompted for regulatory arbitrage, regulatory capture, administrative lapses by regulators (because of sheer volume of laws, enforceability issues and possible confusion) and amplifies conflict of interest among participants or agency problems. And all these get to be reflected on distorted price signals. I'd like to add that inflation, as a hidden tax, is a major contributor to De Soto's property rights-rule of law dilemma.

In Greg Ransom's Hayek Center (where I sourced this, thanks Greg...) adds that... (bold highlight mine)

``My ancestors recorded property right claims with a central registrar in the no-mans land of Oregon when the region had no legitimately recognized government. The people of the region followed customs of law and governance share among the English and Americans, with the anticipation that their property rights claims would later be recognized by the U. S. government when the region became part of the United States. The story is recounted in Nimrod: Courts, Claims and Killing on the Oregon Frontier by Ronald Lansing of the Lewis & Clark School of Law. Yes, remarkably enough, the story is a murder mystery."

my comment: more evidence that property rights had been observed outside of the realm of government.