True confidence does not come from “you can trust us if we screw up because someone else will bail you out” but from “you can trust us because it is demonstrably in our interest to make sure we don’t screw up”. Deposit insurance is an inferior confidence product – one might even say, a confidence trick—Kevin Dowd

In this issue

Mounting Cracks in the PSEi 30: How Structural

Imbalances Are Amplifying Market Stress

I.

The PSEi 30’s February and 2025 Performance

II. PSE’s Market Internals Remain Bearish

III. Is This a Regional Trend? Emerging Signs of Asian

Financial Crisis 2.0?

IV. PSEi 30’s Mounting Market Imbalances

V. Symptoms of Capital Consumption: Despite Surging Credit

Expansion, Falling Liquidity and Diminishing Returns

VI. Share Buybacks as Panacea?

VII. The Path to Full-Fractional Reserve Banking and Deposit Insurance Expansion: A False Sense of Security?

Mounting Cracks in the PSEi 30: How Structural Imbalances Are Amplifying Market Stress

The erosion of a major rally this February following January’s selloff reveals the underlying structural fragilities and operating dynamics of the Philippine Stock Exchange.

I.

The PSEi 30’s February and 2025 Performance

Figure 1

Echoing January’s 4.01% end-of-month selloff, the final trading day of February saw a similar 2.06% pre-closing plunge, erasing nearly half of the recovery gains the PSEi 30 had posted for the month. (Figure 1, upper and lower images)

While it may be convenient to attribute this last-minute market move to portfolio rebalancing, it primarily reflected underlying trend weakness and growing fragility in the PSEi 30.

A portion of January 2025’s selloff was driven by changes in PSEi membership.

In contrast, February’s decline was largely fueled by massive foreign money outflows.

Despite this, the headline index ended February up 2.31% month-over-month (MoM), yet remained down 13.63% year-over-year (YoY) and was still 8.13% lower year-to-date (YTD) in 2025.

II. PSE’s Market Internals Remain Bearish

Why do internal market activities signal a bearish backdrop?

Figure 2

1. Weak Volume Trend

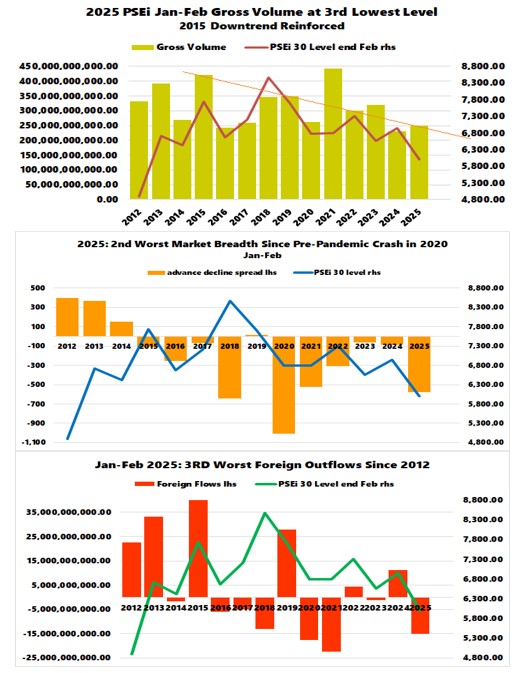

Despite a 7.6% improvement in the PSE’s two-month gross volume, it marked the third-lowest level since 2012, reinforcing a volume downtrend that has persisted since 2015. The 2021 volume spike—an anomaly fueled by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP)’s Php 2.3 trillion historic injections into the financial system—merely highlighted the short-lived effects of the banking system’s pandemic-era rescue. (Figure 2, topmost diagram)

2. Broad-Based Selling Pressure

The two-month selling spree has been widespread. Market breadth, as measured by the advance-decline spread, recorded its second-worst performance since the pandemic crash of March 2020. (Figure 2, middle graph)

3 Persistent Foreign Outflows

In 2025, foreign outflows accounted for the third-largest capital exodus since 2012. Foreign trade made up 50.8% of gross volume, highlighting that selling pressure in the PSEi 30 was exacerbated by weak local investor support. Foreign capital has played the role of the marginal price setter, and its exit underscores the lack of domestic buying power or the dearth of local savings. (Figure 2, lowest chart)

III. Is This a Regional Trend? Emerging Signs of Asian Financial Crisis 2.0?

Figure 3

The sustained foreign money outflow suggests that the phenomenon extends beyond the Philippines.

In 2025, the PSEi 30 ranked as the third-worst-performing equity benchmark in Asia. (Figure 3 topmost and middle graphs)

More broadly, the four largest ASEAN indices have exhibited pronounced weakness since Q3 2024.

If this trend continues, it could lay the groundwork for a potential Asian Financial Crisis 2.0.

IV. PSEi 30’s Mounting Market Imbalances

A deeper look at the PSEi 30 reveals intensifying distortions:

The Financial Index/PSEi 30 has surged to consecutive all-time highs, reflecting massive outperformance since the BSP's historic banking sector rescue during the pandemic recession. (Figure 3, lowest pane)

Conversely, the Property Index/PSEi 30, representing banks’ largest clients, has plunged to its lowest level since 2012. In other words, most of the selling pressure in the PSEi 30 has emanated from this sector.

Figure 4

The cumulative free float shares of the three largest banks have hit all-time highs as of February 28, suggesting that without intervention from the so-called “national team,” the PSEi 30 would have been substantially lower. (Figure 4, topmost image)

V. Symptoms of Capital Consumption: Despite Surging Credit Expansion, Falling Liquidity and Diminishing Returns

Despite back-to-back record highs in systemic leveraging—measured by the combined growth of universal commercial bank loans and public debt in pesos—the PSEi 30 continues to suffer from diminishing YoY returns. (Figure 4, middle image)

This is also reflected in the banking system’s all-time low cash-to-deposits ratio, a key liquidity measure. (Figure 4, lowest window)

The broader implication is clear: massive liquidity injections via credit expansion have led to capital consumption rather than productive investment. This is evident in the declining productivity rate of the economy and diminishing returns on stock market investments.

It is also misleading to blame the PSE’s underperformance on local investors shifting to foreign assets such as offshore stocks or cryptocurrencies. While it may be true for some, the more pressing issue is the depletion of domestic savings.

VI. Share Buybacks as Panacea?

So, how does the establishment help resolve this predicament? While they might claim their shares are "undervalued"—indicating a perceived 'market failure'—Metro Pacific, for instance, opted to delist.

Figure 5

SM Investments made a similar claim while observing their diminishing clout, reflected by their declining share of the free float capitalization in the PSEi 30.

In response, they recently launched a P60 billion share buyback program, "the largest ever announced by a Philippine corporation," aimed at purchasing an estimated 77 million shares, or 6% of the company's outstanding shares.

Could this, however, signal a panic reaction?

Some listed companies use their shares as collateral for loans or as currency in the context of mergers, often with price floors stipulated in their covenants.

VII. The Path to Full-Fractional Reserve Banking and Deposit Insurance Expansion: A False Sense of Security?

This fragility dilemma is further aggravated by the BSP’s recent reserve requirement ratio (RRR) cuts—and strikingly, the central bank is now proposing a transition to FULL fractional reserve banking, with plans to lower the RRR to ZERO.

We previously discussed it here.

The Philippines is NOT the U.S., which can afford zero RRR rates due to its deep and diversified capital markets.

In contrast, systemic risks in the Philippines are being amplified as banks have increasingly monopolized the nation’s total financial resources, leaving the economy vulnerable to liquidity shocks and credit misallocation

Meanwhile, the Philippine Deposit Insurance Corporation (PDIC) has doubled its maximum deposit insurance

coverage. However, this

comes at a time when the rate of qualified deposits continues to decline.

Figure 6

As of Q3 2024:

-Total insured deposits had been trending downward since 2011, reaching just 18.3% of total deposits. (Figure 6, upper chart)

-Of this, only 9.83% were fully insured, while 8.4% were partially insured.

Although this decline is attributed to aggressive bank credit expansion, which has inflated deposit levels, it has barely delivered a proportional increase in deposits.

As an aside, it is unclear how much in assets the PDIC has to support such claims.

VIII. In Summary: Intensifying Imbalances and Amplified Volatility; Opportunity? Mining Index

The PSEi 30’s performance in 2025 reflects worsening structural imbalances, manifested through magnified volatility.

To be sure, while fierce bear market rallies can occur, this does not mean that rising prices will eliminate these risks.

Here’s what we’re watching: one key development has been gold’s record-breaking surge.

If this trend continues, it could help provide a boost to the mining index, which has been quietly gaining upside momentum at the margins. (Figure 6, lowest pane)

This represents a fringe (or niche) opportunity with potential.

Nota bene: This article offers market insights but does not constitute a recommendation or call to action.