As a plunging currency and a slowdown in consumption hamper India’s once vibrant economy, many industries are facing the prospect of plummeting profits.Usually at this time of the year, consumer companies look ahead to windfall profits. Starting in September, consumption increases because it is considered auspicious to buy new products such as cars and televisions for the main Hindu festival, Diwali, to be celebrated in November.But this year the mood in most corporate headquarters is pessimistic. The reason: the plunging rupee. India’s currency has lost nearly 20 percent of its value in recent months, pushing up costs for companies that rely on imports of raw materials. That is a large number ranging from electronics to automobiles.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Parallel Universe: India Edition

Friday, September 06, 2013

India Crisis Watch: Is it Panic Time?

For the last 24-hours, banker and fund manager friends of mine have been telling me stories about oil refinery deals in North Korea, their crazy investments in Myanmar, and the utter exodus of global wealth that is finding its way to Singapore.My colleagues reported that in the last few weeks they’ve begun seeing two new groups moving serious money into Singapore– customers from Japan and India.Both are very clear-cut cases of people who need to get their money out of dodge ASAP.In Japan, the government has indebted itself to the tune of 230% of GDP… a total exceeding ONE QUADRILLION yen. That’s a “1″ with 15 zerooooooooooooooos after it.And according to the Japanese government’s own figures, they spent a mind-boggling 24.3% of their entire national tax revenue just to pay interest on the debt last year!Apparently somewhere between this untenable fiscal position and the radiation leak at Fukishima, a few Japanese people realized that their confidence in the system was misguided.So they came to Singapore. Or at least, they sent some funds here.Now, if the government defaults on its debts or ignites a currency crisis (both likely scenarios given the raw numbers), then those folks will at least preserve a portion of their savings in-tact.But if nothing happens and Japan limps along, they won’t be worse off for having some cash in a strong, stable, well-capitalized banking jurisdiction like Singapore.India, however, is an entirely different story. It’s already melting down.My colleagues tell me that Indian nationals are coming here by the planeful trying to move their money to Singapore.Over the last three months, markets in India have gone haywire, and the currency (rupee) has dropped 20%. This is an astounding move for a currency, especially for such a large economy.As a result, the government in India has imposed severe capital controls. They’ve locked people’s funds down, restricted foreign accounts, and curbed gold imports.People are panicking. They’ve already lost confidence in the system… and as the rupee plummets, they’re taking whatever they can to Singapore.As one of my bankers put it, “They’re getting killed on the exchange rates. But even with the rupee as low as it is, they’re still changing their money and bringing it here.”Many of them are taking serious risks to do so. I’ve been told that some wealthy Indians are trying to smuggle in diamonds… anything they can do to skirt the controls.(This doesn’t exactly please the regulators here who have been trying to put a more compliant face on Singapore’s once-cowboy banking system…)The contrast is very interesting. From Japan, people who see the writing on the wall just want to be prepared with a sensible solution. They’re taking action before anything happens.From India, though, people are in a panicked frenzy. They waited until AFTER the crisis began to start taking any of these steps. As a result, they’re suffering heavy losses and taking substantial risks.

While it may be true that Mr. Rajan has a magnificent track record of understanding central banks and the entwined interests of the banking system coming from the free market perspective, in my view, it is one thing to operate as an ‘outsider’, and another thing to operate as a political ‘insider’ in command of power.Mr. Rajan will be dealing, not only conflicting interests of deeply entrenched political groups, but any potential radical free market reforms are likely to run in deep contradiction with the existing statutes or legal framework from which promotes the interests of the former.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

More Signs of the End of Easy Money: Following Brazil, the Indian Government Raises Interest Rates

India stepped up efforts to help the rupee after its plunge to a record low, raising two interest rates in a move that escalates a tightening in liquidity across most of the biggest emerging markets.The central bank announced the decision late yesterday after Governor Duvvuri Subbarao earlier in the day canceled a speech to meet the finance minister. The RBI raised two money-market rates by 2 percentage points and plans to drain 120 billion rupees ($2 billion) through bond purchases.Indian rupee forwards jumped the most in 10 months, and the RBI’s move yesterday left Russia as the only BRIC economy to not have reined in funds in its financial system. Brazil has raised its benchmark rates three times this year and a cash squeeze in China sent interbank borrowing costs soaring to records last month.

Saturday, May 18, 2013

Why the Indian Government’s War on Gold will Fail

The imperative to contain gold import has become urgent. The recent surge in gold demand is however creating some distortions and need to be rolled back to boost growth by reversing the trend of declining financial savings and keeping CAD* within prudent limit by contain gold demand.

It could have posed as a model scheme to curtail gold imports. In order to stifle India’s appetite for gold, the government has introduced inflation index bonds. The first tranche amounting to around $364 million (R20 billion) is to be introduced on June 4.Inflation Indexed Bonds (IIBs) are a new category of debt instruments to be introduced in India, where the coupon and principal amount would be linked to the rate of wholesale price inflation with a lag of four months. The authorities have said the objective of introducing such bonds is to channelise savings into productive sources of instruments from unproductive ones like gold.Slowly but surely, there seems to be an anti-gold campaign that is at play in India. The concerted effort by the Indian government to discredit gold by imposing several curbs, and channelise consumers away from the precious metal, indicates a desperation that has not gone unnoticed by savvy investors.“The government is making it too expensive for retailers to sell gold, especially when prices have hit new all-time lows. Retailers are forced to apply hefty mark-up given the new curbs,” said Manohar Kedia, of Kedia Jewellery House.

Knowing fully well that Indians cannot keep away from gold for long, the Reserve Bank of India first hauled up banks for selling gold coins, then came down hard on gold retailers and bullion houses. Now, they have turned their attention on investors, urging them to invest in debt instruments.Further, in order to moderate the demand for gold for domestic use, the government has also restricted the import of gold on a consignment basis. A major bullion retailer in Mumbai said this would prove to be a major hurdle for exporters.For, only those exporting gold jewellery will first have to impose on banks for each consignment, given that banks will henceforth be allowed to import gold only to meet the genuine needs of exporters of gold jewellery.

Over centuries and millennia, gold has become an inseparable part of the Indian society and fused into the psyche of the Indian. Having passed through fire in its process of evolution it is seen as a symbol of purity, the seed of Agni, the God of fire. Perhaps this is why it is a must at every religious function in India. Gold has acted as the common medium of exchange or the store of value across different dynasties in India spanning thousands of years and countless wars. Thus wealth could be preserved inspite of wars and political turbulence. For centuries, gold has been a prime means of saving in rural India.

Since 1950, India ran into trade deficits that increased in magnitude in the 1960s. The Government of India had a budget deficit problem and therefore could not borrow money from abroad or from the private sector, which itself had a negative savings rate. As a result, the government issued bonds to the RBI, which increased the money supply, leading to inflation. In 1966, foreign aid, which was hitherto a key factor in preventing devaluation of the rupee was finally cut off and India was told it had to liberalise its restrictions on trade before foreign aid would again materialise. The response was the politically unpopular step of devaluation accompanied by liberalisation. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 led the US and other countries friendly towards Pakistan to withdraw foreign aid to India, which further necessitated devaluation. Defence spending in 1965/1966 was 24.06% of total expenditure, the highest in the period from 1965 to 1989. This, accompanied by the drought of 1965/1966, led to a severe devaluation of the rupee. Current GDP per capita grew 33% in the Sixties reaching a peak growth of 142% in the Seventies, decelerating sharply back to 41% in the Eighties and 20% in the Nineties.

The economic backwardness of such countries as India consists precisely in the fact that their policies hinder both the accumulation of domestic capital and the investment of foreign capital. As the capital required is lacking, the Indian enterprises are prevented from employing sufficient quantities of modem equipment, are therefore producing much less per man-hour, and can only afford to pay wage rates which, compared with American wage rates, appear as shockingly low.There is only one way that leads to an improvement of the standard of living for the wage-earning masses — the increase in the amount of capital invested. All other methods, however popular they may be, are not only futile, but are actually detrimental to the well-being of those they allegedly want to benefit.

With regard to financial access and penetration, India ranks low when compared with the OECD countries. India offered 6.33 branches per 100,000 persons whereas OECD countries provided for 23-45 branches per 100,000 people in 2009. For India, the number of branches and ATMs per 100,000 persons has increased to 7.13 and 5.07 in 2010.In India, the penetration of banking services is very low. Merely, 57% of population has access to a bank account (savings) and 13% of population has debit cards and 2% has credit cards. This represents the unmet demand and the scope for expansion for the banks in India.

The size of India’s “informal” economy, meanwhile, handicaps efforts to track the number of Indians who are gainfully employed. Four out of five urban workers—who collectively produce an estimated three-quarters of the country’s output—are informally employed. That means their work does not show up in official figures on productivity, innovation, social mobility and other standard metrics of progress. It’s possible to debunk some of the myths about India’s work force—three-quarters of self-employed workers in urban areas, for example, are in single-person businesses or family enterprises without hired labor, rather than upwardly mobile entrepreneurs—but a clear picture of exactly how many Indians are working, and where, remains elusive.

Pune’s wide boys aside, the traditional gold consumers are southern peasants buying jewellery. They have no access to formal finance; gold requires no paperwork, incurs no tax and is liquid. But over the past decade the mania has spread. By weight consumption has doubled, for several reasons: a surge in money earned on the black market; investors chasing the gold price; and the dismal returns savers get from deposit accounts. Real interest rates are low, reflecting high inflation and a repressed financial system that is geared to helping the state finance itself.

India has tried coercion. Between 1947 and 1966 it banned gold imports. After that it used a licensing system. Neither worked. Smuggling soared and policymakers were reduced to tinkering with airport-baggage allowances. By 1997 trade was liberalised.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Massive Earth Hour (Blackouts) in India

Massive power outages in India has affected more than half of the population.

From the Bloomberg, (bold highlights mine)

India’s electricity grid collapsed for the second time in as many days, cutting off more than half the country’s 1.2 billion population in the nation’s worst power crisis on record.

Commuter trains in the capital stopped running, forcing the operator, Delhi Metro Rail Corp., to evacuate passengers, spokesman Anuj Dayal said. NTPC Ltd. (NTPC), the biggest generator, shut down 36 percent of its capacity as a precaution, Chairman Arup Roy Choudhury said by telephone. More than 100 inter-city trains were stranded, Northern Railway spokesman Neeraj Sharma said, as the blackout engulfed states in the north and east.

So what went wrong?

From the same article…

State-owned Power Grid Corp. of India Ltd., which operates the world’s largest transmission networks, manages power lines including in the northern and eastern regions. NTPC and billionaire Anil Ambani-controlled Reliance Power Ltd. (RPWR) operate power stations in north India that feed electricity into the national grid. The northern and eastern grids together account for about 40 percent of India’s total electricity generating capacity, according to the Central Electricity Authority.

The grids in the east, north, west and the northeast are interconnected, making them vulnerable, said Jayant Deo, managing director of the Indian Energy Exchange Ltd. The outage has also spread to seven additional states in the northeast, NDTV television channel reported.

“Without a definitive plan by the government to gradually bring the grids back online, this problem could absolutely get worse,” Deo said.

Singh is seeking to secure $400 billion of investment in the power industry in the next five years as he targets an additional 76,000 megawatts in generation by 2017. India has missed every annual target to add electricity production capacity since 1951.

Well in reality, the root of the problem hasn’t been about ‘definite plans’ by the Indian government, but rather largely due to India’s statist political economy.

Again from the same article…

Improving infrastructure, which the World Economic Forum says is a major obstacle to doing business in India, is among the toughest challenges facing Singh as he bids to revive expansion in Asia’s third-largest economy that slid to a nine- year low of 5.3 percent in the first quarter.

Tussles over policy making with allies in the ruling coalition, corruption allegations and defeats in regional elections have weakened Singh’s government since late 2010.

Must I forget, artificial electricity demand has partly been boosted by India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), who passes the blame on others.

Again from the same article

The Reserve Bank of India, which has blamed infrastructure bottlenecks among others for contributing to the nation’s price pressures, today refrained from cutting interest rates even as growth in the $1.8 trillion economy cooled to a nine-year low in the first quarter.

Indian consumer-price inflation was 10.02 percent in June, the fastest among the Group of 20 major economies, while the benchmark wholesale-price measure is more than 7 percent.

The last time the northern grid collapsed was in 2001, leaving homes and businesses without electricity for 12 hours. The Confederation of Indian Industry, the country’s largest association of companies, estimated that blackout cost companies $107.5 million.

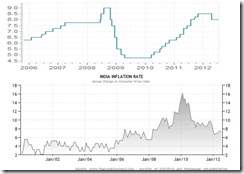

Chart above from global-rates.com and tradingeconomics.com

India’s bubble ‘easy money’ (upper window) policies in 2009-2010 fueled a stock market recovery (below window) in 2010.

On the other hand, the then negative interest rate regime also stoked local inflation (pane below policy interest rates).

This has prompted the Reserve Bank of India to repeatedly raise policy rates or tightened monetary policy. The result has been to put a brake on India’s economy and the stock market rebound.

Part of the Indian government’s attack on her twin deficits, which has been blamed for inflation through the decline of the currency, the rupee, has been to turn the heat on gold imports and bank gold sales.

Aside from demand from the monetary policies, electricity subsidies has also been a culprit. Farmers have been provided with subsidized electricity. Such subsidy has not only increased demand for power but also put pressure on water supplies.

Environmentalists would likely cheer this development as ‘Earth Hour’ environment conservation.

Yet India’s widespread blackouts are evidences and symptoms of government failure.

Rampant rolling blackouts extrapolate to severe economic dislocations which not only to means inconveniences but importantly prolonged economic hardship.

Thursday, June 11, 2009

India's Surging Markets Lures Companies From The Government and The Private Sector To Raise Financing

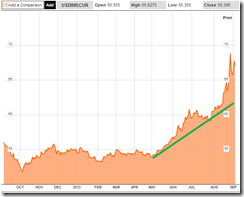

From the trough, India's BSE 30 is up about 84% and is 26% shy from its 2008 peak.

From the trough, India's BSE 30 is up about 84% and is 26% shy from its 2008 peak. The Indian rupee has also rallied furiously since the simultaneous trough in the stock and currency markets.

The Indian rupee has also rallied furiously since the simultaneous trough in the stock and currency markets.According to the Wall Street Journal, ``So far this year, issues of new shares have been scarce. But with the Bombay Stock Exchange's benchmark index at a 10-month high, many companies have plans to raise capital to bolster balance sheets and fund growth, bankers say.

``The new government's budget, scheduled for release in early July, also could usher in new sales of stakes in public companies. The frenzy may be welcome news to investors looking to ride a rapid rise in India's stock market over the past few months...

``Data provider Thomson Reuters expects $50 billion of new shares to be issued in India this year. So far, there has been just $1 billion.

Again from the same article, ``On the IPO front, state-owned hydro-power outfit NHPC Ltd. and oil-exploration company Oil India Ltd. are expected to issue shares. On Monday, Rahul Khullar, the outgoing top bureaucrat in the department in charge of state company disinvestment, said the government is likely to sell stakes in NHPC and Oil India by September, followed by six to seven other companies before March 31, 2010.

``The government's budget could offer further divestment plans amid the need to stimulate the economy without severely worsening the fiscal deficit.

``Air India, India's national airline, and state-run telecommunications company Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd., or BSNL, are likely to sell some shares, market watchers say."

The phenomenal activities in India are likely to be replicated in major Emerging Markets and in Asia.