As China’s one-child policy comes officially to an end, it is time to write the epitaph on this horrible experiment — part of the blame for which lies, surprisingly, in the West and with green, rather than red, philosophy. The policy has left China with a demographic headache: in the mid-2020s its workforce will plummet by 10 million a year, while the number of the elderly rises at a similar rate.The difficulty and cruelty of enforcing a one-child policy was borne out by two stories last week. The Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, who directed the Beijing Olympics’ opening ceremony in 2008, has been fined more than £700,000 for having three children, while another young woman has come forward with her story (from only two years ago) of being held down and forced to have an abortion at seven months when her second pregnancy was detected by the authorities.It has been a crime in China to remove an intra-uterine device inserted at the behest of the authorities, and a village can be punished for not reporting an illegally pregnant inhabitant.I used to assume unthinkingly that the one-child policy was a communist idea, just another instance of Mao’s brutality. But the facts clearly show that it was a green idea, taken almost directly from Malthusiasts in the West. Despite all his cruelty to adults, Mao generally left reproduction alone, confining himself to the family planning slogan “Later, longer, fewer”. After he died, this changed and we now know how.Susan Greenhalgh, a professor of anthropology at Harvard, has uncovered the tale. In 1978, on his first visit to the West, Song Jian, a mathematician employed in calculating the trajectories of missiles, sat down for a beer with a Dutch professor, Geert Jan Olsder, at the Seventh Triennnial World Congress of the International Federation of Automatic Control in Helsinki to discuss “control theory”. Olsder told Song about the book The Limits to Growth, published by a fashionable think-tank called the Club of Rome, which had forecast the imminent collapse of civilisation under the pressure of expanding population and shrinking resources.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Saturday, January 18, 2014

How Western Environmentalism Shaped China’s One Child Policy

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Has Thomas Malthus been a free market friend or a foe?

Robert Malthus (his friends called him “Bob”) was one of the primary interpreters of Adam Smith for the generation after Smith. Indeed, a lot of people who pick on “Thomas” Malthus get Bob Malthus wrong.That’s not to say that Malthus was right about everything. But even more than Smith, Malthus’s economics built upon the idea that all humans similarly respond to incentives; and he thereby rejected the idea of natural hierarchy. Writing in a country that had excessive restrictions on labor markets—take a look at the Poor Laws—Malthus was an advocate of free labor markets. And Malthus argued that private property rights, free markets, and an institution that would ensure that both parents were financially responsible for the children they bore (that is, marriage) were essential features of an advanced civilization.“Wait a minute,” you may be thinking. “Are we talking about the Malthus who claimed back in 1798 in his Essay on the Principle of Population that population growth would decrease per capita wellbeing? Isn’t this the guy who argued that the combination of population growth and natural resource scarcity would create catastrophic consequences, including disease, starvation, and war for much of the human race? And didn’t he miss the benefits of entrepreneurship and innovation, blinded as he was by the fallacy of land scarcity?”That Malthus—let’s call this one “Tom”—is more a creature of ideological opponents of markets than of Malthus’s own writings. So maybe we should revisit Malthus and see what he actually said.It all begins with a thought experiment: what would happen to human population in the absence of any institutions?The answer is the population principle, which is the only thing most people know about Malthus. And it’s largely correct. In the absence of institutions, humans are reduced to their biological basics: Like animals, humans share the necessity to eat, and the passions that lead to procreation. To eat, humans must produce food. To procreate, humans must have sex. If there are no institutions, human population will behave like any animal population and increase to the limit of their ecology’s carrying capacity.The biological model is simplistic; it treats humans as mere biological agents. It is this biological model that produces all the results people usually associate with Malthus’s name. And it’s not very far off from people’s conditions when their institutions have suddenly been disrupted by things like conquest, revolution, or war. (Consider the dual problems of war and drought that resulted in famine for Ethiopians in 1983–85, for example.)But for Bob Malthus, the biological model is only a starting point. The model set up his next concern: the incentives created by different institutional rules for families’ fertility choices (in Malthus’s terms: the decision to delay marriage). The comparative institutional analysis that emerged from his further investigation became the basis for his defense of the institutional framework of a free society.

It turns out the mainstream view of Tom (as opposed to the real “Bob”) was first created by opponents of markets, sustained throughout the nineteenth century by lovers of hierarchy, and resuscitated in the twentieth century by environmentalists committed to the view that there are natural limits to economic growth. These environmentalists picked out the bits they liked and scrapped the rest, as it suited their agendas.

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Why the Neo-Malthusian Premise of “Peak Resources” are Misguided

Yet whether it is oil or copper or iron ore or whatever resource, people insist on relying on the same faulty reasoning that “the easy stuff is gone.” They continue to make the same tired case for chronic natural resource shortages and a decline in our standard of living.The great economist Joseph Schumpeter’s (1883-1950) criticism of the Malthusian position still holds. On Malthus and his ilk, he wrote: “The most interesting thing to observe is the complete lack of imagination which that vision reveals. Those writers lived at the threshold of the most spectacular economic developments ever witnessed.” Yet they missed it.So here is my prediction: I believe we are on the cusp of even greater levels of innovation and development — another industrial revolution is in progress right now. So ignore the gloom and doom on natural resources. Contra Grantham, the days of abundant resources and falling prices are far from over.

Deep-sea mining is poised as a major growth industry over the next decade, as large developing-world populations drive consumer demand for metal-containing products, climate change makes previously inaccessible regions like the Arctic Ocean seabed attainable, and improved extraction technologies turn previously uneconomical rock into paydirt.Cindy Van Dover is a Professor of Biological Oceanography at Duke University and a leading voice in the development of policy and management strategies for deep-sea extraction activities. Van Dover has studied the ecology of hydrothermal vents for years, and she takes a measured, pragmatic approach to the coming industrialization of her study sites. If mining is going to happen – a event that the more strident faction of the environmental movement will no doubt contest – “we need to work with industry to make sure we do it right,” says Van Dover.

A newly launched asteroid miner is looking to the history of deep sea mining as it attempts to navigate laws governing exploitation of space.Deep Space Industries, which rolled out its plan for space mining today at a news conference in the Santa Monica Museum of Flying in California, said the laws regarding resource mining beyond the earth are largely unformed, and the company will rely on co-operation between the main players. (Video embed of the press conference is below.)"If you look at parallels, like deep sea mining, that went forward without a global treaty. The companies that wanted to do deep sea mining shook hands: 'We won't interfere with you if you don't interfere with us', that was the general approach going forward," said David Gump, Deep Space's chief executive officer.Gump said the company will be relying on the 1967 space treaty, which he says will give the company the right to utilize space resources but will not grant the right to claim any sovereign territory.

“[N]atural resources are not finite in any meaningful economic sense, mind-boggling though this assertion may be. The stocks of them are not fixed but rather are expanding through human ingenuity.”

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

7 Billion People: Boon or Bane?

The United Nations says that world population have reached 7 billion.

In attempting to visualize the impact of 7 billion people The Economist writes,

THE UN's doughty demographers have declared that October 31st is the day on which the world's population reached 7 billion. They may be wrong (the UN got the timing of the 6 billionth birth out by a couple of years) but no matter: the announcement has triggered celebrations in maternity wards around the globe and a hunt for the 7 billionth child. Yet the growth in the world’s population is actually slowing. The peak was in the late 1960s, when it was rising by almost 2% a year. Now the rate is half that. The last time it was so low was in 1950, when the death rate was much higher. The result is that the next billion people will take 14 years to arrive, the first time that a billion milestone has taken longer to reach than the one before. The billion after that will take 18 years. Where will all these people fit? The chart below, worked out on a maximum population density of six Economist staffers per square metre, gives the space needed to accommodate the world's population at various points in history, expressed in multiples of the borough of Manhattan. Looked at another way, each of us now has the equivalent of Red Square to ourselves.

7 billion represents merely a statistical estimate which most likely is an inaccurate measure of the real number of the world’s population.

Yet, the UN’s declaration seems loaded with political inferences.

For instance, the Economist article above tries to project maximum land allocated per individual or a population density. But this would be a chimera for the simple reason that all land area are not the same (e.g. mountains are different from coastline or from hills or from plateau; there are private owned and public owned) and that each individual does not use up or require as much space as what the Economist implies.

So the framing from the 7 billion figure could essentially foster political alarmism over a potential conflict from growing population relative to the scarcity of land which is fundamentally not only false but unrealistic.

The other implication of the UN’s hype is to give neo-Malthusians (who falsely believed that overpopulation would translate to a catastrophe for mankind or the Malthusian Catastrophe) room to advocate for more political controls on everyone. Their focal point has been centered on the strains to access scarce resources and to the environmental impact from a growing population.

Following charts from World Bank-Google Public Data

Yet even if there is some semblance of truth to the claim that we are now 7 billion people, the $7 billion question is that how have we been able to successfully reach this state in defiance of the doom mongers’ expectations of a ‘catastrophe’? And importantly if such factors will continue to support even a larger population?

The Economist rightly points out that world fertility rate have been going down.

If this slowing fertility trend should continue, then population growth trends would imply for a slowdown or even a potential peaking.

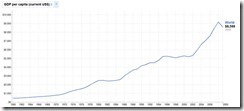

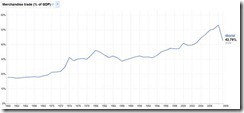

Nevertheless, another very important aspect that has supported today’s 7 billion people has been a huge jump in GDP per capita that coincides with the slowing fertility growth

The substantial improvement in per capita GDP has mostly been because of globalization and a more pervasive adaption of economic freedom.

Competition in free markets has been cultivating and accelerating the rate of technological innovations that has helped in resolving the scarcity problem in many aspects such as in the science and medicine, information and communications, business process and etc..

Largely uncelebrated hero Norman Borlaug discovered high yielding wheat varieties which he combined with modern agricultural techniques which paved way for the green revolution. Mr. Borlaug was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and was known as the ‘father of green revolution’ who has been credited with saving over a billion people from starvation

And further advancements in technology whose costs have materially decreased have became available to a wider range of people which has increased people's lifespans

The very impressive author Matthew Ridley wearing his Julian Simon hat (the famous free market economist who made a controversial bet against Malthusian Paul Elrich and won) sums up at the Wall Street Journal on why population growth trends will slow

(bold emphasis mine)

Birth rates have gone down because of prosperity, not poverty. Everywhere it has occurred, it has followed a fall in child mortality and famine and an increase in income and education. The wider availability of contraception has been necessary, even vital, for this shift, but it has not been sufficient.

To a biologist, the demographic transition is both surprising and intriguing. No other species drops its birth rate when its food supply increases. Frankly, no expert has yet fully explained the phenomenon. It remains something of a demographic enigma.

The best guess is that modern society causes human beings to switch their reproductive strategy from quantity to quality. Thus, once child mortality drops and paid work becomes available to the children of subsistence farmers, parents become more interested in getting one or two children into education or jobs than in begetting lots of heirs and spares for the farm.

Whatever the explanation, history shows that top-down policies aimed directly at population control have generally proved less successful than bottom-up ones aimed at human welfare, which get population control as a bonus. The faster poor countries can grow their economies, the slower they will grow their populations.

While present developments has generated much progress, there are still many afflicted by poverty. That’s because there continues to be meaningful resistance in embracing a bottom up approach in dealing with socio-economic development.

It's really not about the number of people but the process or the means by which people use to sustain their living. This means, in general, the world is much better off with MORE PRODUCTIVE people.

Thursday, May 19, 2011

Can We Survive a World with 9 billion people?

Prolific author Matt Ridley says yes (bold emphasis mine)...

We trebled yields in the last 60 years without taking extra land under the plough. If we did that again – by getting fertilizer to farmers in Africa and central Asia, by cutting losses to pests and droughts through ever more subtle genetic manipulation, by improving roads and encouraging trade – then we could feed nine billion better than we feed seven billion today. And still retire huge swathes of land from farming to rainforest and other forms of wilderness.

The two most effective policies for frustrating this uplifting ambition are: organic agriculture and renewable bio-energy. Organic farming means growing your nitrogen fertilizer rather than fixing it from the air. That requires more land, either grazed by cattle or planted with legumes. The quickest way to destroy what wilderness we have left is to go organic. Bio-energy (growing crops to make fuel or electricity) takes food out of the mouths of the poor. In 2010, the world diverted 5% of its grain crops into making fuel, displacing just 0.6% of oil use yet killing an estimated 192,000 people by tipping them into malnutrition through higher food prices. We should stop such madness now.

...provided environmental politics would not lead to vicious government meddling which would subvert earlier victories with deleterious policies that would function as the proverbial cure which is worse than the disease.

He writes about how Malthusians like Paul Ehrlich, who wrongly forecasted for a worldwide cataclysmic famine, had mainly been foiled by creative persistency of the father of Green Revolution Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug, one of the genuine unsung heroes of the world (my earlier post here).

He also writes about how technology has substantially increased farming efficiency which has led to a massive reduction in land usage for agriculture. (bold emphasis mine)...

We currently feed nearly seven billion people by farming about 38% of the land surface of the planet. If we wanted to feed that many people by using the techniques, varieties and – mostly organic – fertilizers of the 1950s, we would need to cultivate roughly 84% of the land surface. There goes the rain forest, the national parks, the wetlands. The intensification of agriculture has saved wilderness.

...and also how famine prevention defused the population time bomb.

Read Mr. Ridley’s fantastic article here

Bottomline: Mr. Ridley bets on human ingenuity (and not on econometric models) brought upon mostly by free trade. And so do I.