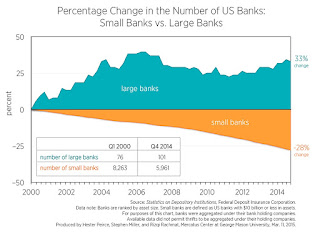

The “Big Four” retail banks in the United States collectively hold 45% of all customer bank deposits for a total of $4.6 trillion.The fifth biggest retail bank, U.S. Bancorp, is nothing to sneeze at, either. It’s got 3,151 banking offices and employs 65,000 people. However, it still pales in comparison with the Big Four, holding only a mere $271 billion in deposits.Today’s visualization looks at consolidation in the banking industry over the course of two decades. Between 1990 and 2010, eventually 37 banks would become JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and Citigroup.Of particular importance to note is the frequency of consolidation during the 2008 Financial Crisis, when the Big Four were able to gobble up weaker competitors that were overexposed to subprime mortgages. Washington Mutual, Bear Stearns, Countrywide Financial, Merrill Lynch, and Wachovia were all acquired during this time under great duress.The Big Four is not likely to be challenged anytime soon. In fact, the Federal Reserve has noted in a 2014 paper that the number of new bank charters has basically dropped to zero.From 2009 to 2013, only seven new banks were formed.“This dramatic reduction in new bank charters could be a concern for policymakers, if as some suggest, the decline has been caused by increased regulatory burden imposed in response to the financial crisis,” the authors of the Federal Reserve paper write.Competition from small banks has dried up as a result. A study by George Mason University found that over the last 15 years, the amount of small banks in the country has decreased by -28%.Big banks, on the other hand, are doing relatively quite well. There are now 33% more big banks today than there were in 2000.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Infographic: The US Banking Oligopoly in One Chart; The Roots of Too Big to Fail

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Quote of the Day: The Roots of the Too Big To Fail Doctrine

For fractional reserve banking can only exist for as long as the depositors have complete confidence that regardless of the financial woes that befall the bank entrusted with their “deposits,” they will always be able to withdraw them on demand at par in currency, the ultimate cash of any banking system. Ever since World War Two governmental deposit insurance, backed up by the money-creating powers of the central bank, was seen as the unshakable guarantee that warranted such confidence. In effect, fractional-reserve banking was perceived as 100-percent banking by depositors, who acted as if their money was always “in the bank” thanks to the ability of central banks to conjure up money out of thin air (or in cyberspace). Perversely the various crises involving fractional-reserve banking that struck time and again since the late 1980s only reinforced this belief among depositors, because troubled banks and thrift institutions were always bailed out with alacrity–especially the largest and least stable. Thus arose the “too-big-to-fail doctrine.” Under this doctrine, uninsured bank depositors and bondholders were generally made whole when large banks failed, because it was widely understood that the confidence in the entire banking system was a frail and evanescent thing that would break and completely dissipate as a result of the failure of even a single large institution.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Video: Iceland's President: Let Banks Go Bankrupt

1:24 Why do you consider banks to be the holy churches of the modern economy?

1:37 The theory that you have to bailout banks is the theory about bankers enjoying their own profit of success and let the ordinary people be the failure...

2:31 If you want your economy to be competitive in the innovative sector of the 21th century, a strong financial sector that takes the talent from these sectors, even a successful financial sector is in fact bad news, if you want your economy to be competitive in the areas which really are the 21st century areas Innovation Technology IT

A smaller population could mean that vested interest groups may have lesser political influence, or perhaps, are easier to deal with compared to the more complex and hugely populated social democratic welfare states as Europe, Japan or the US where power blocs have been deeply entrenched and have significant following in the populace.

But yes, let the banks fail.

Thursday, May 17, 2012

How Government Policies Contributed to JP Morgan’s Blunder

Author and derivatives manager Satyajit Das, ironically a neoliberal, has a superb article at the Minyanville, which elaborates on how regulations and government policies, which I earlier posted, has shaped the incentives of Too Big to Fail institutions to take excessive risks and the failure of regulators to prevent them (all bold emphasis mine)

The large investment portfolio is the result of banks needing to maintain high levels of liquidity, dictated by both volatile market conditions and also regulatory pressures to maintain larger cash buffers against contingencies. Broader monetary policies, such as quantitative easing, have also increased cash held by banks, which must be deployed profitably. Regulatory moves to prevent banks from trading on their own account -- the Volcker Rule -- have encouraged the migration of trading to other areas of the bank, such as liquidity management and portfolio risk management hedging.

Faced with weak revenues in its core operations and low interest rates on cash or secure short term investment, JPMorgan may have been under pressure to increase returns on this portfolio. The bank appears to have invested in a variety of securities, including mortgage backed securities and corporate debt, to generate returns above the firm’s cost of capital.

Again, the failure of models…

Given JPMorgan vaunted risk management credentials and boasts of a “fortress like” balance sheet, it is surprising that the problems of the hedge were not identified earlier. In general, most banks stress test hedges to ensure their efficacy prior to implementation and monitor them closely.

While the $2 billion loss is grievous, the bank’s restatement of its VaR risk from $67 million to $129 million (an increase of 93%) and reinstatement of an older risk model is also significant, suggesting a failure of risk modeling.

The knowledge problem…

Banks are now obliged to report positions and trades, especially certain credit derivatives. This information is available to regulators in considerable detail. Given that the hedge appears to have been large in size (estimates range from ten to hundreds of billions), regulators should have been aware of the positions. It is not clear whether they knew and what discussions if any ensued with the bank.

External auditors and equity analysts who cover the bank also did not pick up the potential problems. Like regulators, they perhaps relied on assurances from the bank’s management, without performing the required independent analysis.

Hayek’s “Fatal Conceit” or the pretentions of knowledge by regulators to apply controls over society or the marketplace…

Legislators and regulators now argue that the rules for portfolio hedging are too wide and impossible to police effectively. In addition, the statutory basis may not support the rule. The legislative intent was intended only to exempt risk-mitigating hedging activity, specifically hedging positions that reduce a bank’s risk. Interestingly, drafters of the portfolio hedging exemption recognized the potential problems, seeking comment on whether portfolio hedging created “the potential for abuse of the hedging exemption” or made it difficult to distinguish between hedging or prohibited trading.

In a recent Congressional hearing, Former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, who helped shape the eponymous provision, questioned whether the volume of derivatives traded was “all directed toward some explicit protection against some explicit risk.”

The pundits have been quick to suggest that the losses point to the need for more stringent regulations. But it is not clear that a prohibition on proprietary trading would have prevented the losses.

In practice, without deep and intimate knowledge of the institution and its activities, it is difficult to differentiate between legitimate investment and trading of a firm’s surplus cash resources or investment capital.

It is also difficult sometimes to distinguish between hedging and speculation. The JPMorgan positions that caused the problems were predicated on certain market movements -- a flattening of the credit margin term structure -- which did not occur.

Hedging individual positions is impractical and would be expensive. It would push up the cost of credit to borrowers significantly. All hedging also entails risk. At a minimum, it assumes that the counterparty performs on its hedge. But inability to legitimately hedge also escalates risk of financial institutions. Ultimately no hedging is perfect. or as author Frank Partnoy told Bloomberg: “The only perfect hedge is in a Japanese garden.”

Additional regulation assumes that the appropriate rules can be drafted and policed. Experience suggests that it will not prevent future problems.

Bankers and regulators have always been seduced by an elegant vision of a scientific and mathematically precise vision of risk. As the English author G.K. Chesterton wrote: “The real trouble with this world [is that]…. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is; its exactitude is obvious but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait.”

In reality it is not just “without deep and intimate knowledge of the institution and its activities” but about having the prior knowledge of the choices of the individuals behind these institutions. This is virtually unknowable.

Finally, the monumental government failure…

How do regulatory initiatives and monetary policy action affect bank risk taking? Central bank policies are adding to the problem of banks in terms of large cash balances which must be then invested at a profit. The implementation of the Volcker Rule may have had unintended consequences. It encouraged moving risk-taking activities from trading desks where the apparatus of risk management may be marginally better established to other parts of banks where there is less scrutiny.

The most important question remains whether any specific action short of banning specific instruments and activities can prevent such episodes in the future. It seems as Lord Voldemort observed in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2: “They never learn. Such a pity.”

People who are blinded by power and or the thought of power never really learn.

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

Who is to blame for JP Morgan’s $2 billion loss?

It’s all about bad decisions, argues Mike Brownfield of the conservative Heritage Foundation

Heritage’s David C. John explains that while JP Morgan’s loss represents a clear failure of management, it’s not a systemic problem that requires or would be fixed by additional regulation. For starters, JP Morgan is a $2.3 trillion bank with a net worth of $189 billion, meaning that this loss reduced the bank’s capital ratio from 8.4 percent to 8.2 percent. In other words, the bank can absorb the loss, and it’s nowhere close to needing any form of federal intervention.

Some more perspective could be gleaned by examining the $3.2 billion loss the U.S. Post Office experienced in the most recent quarter, or the billions lost on risky green energy bets made by President Obama and Energy Secretary Steven Chu. Only those losses weren’t incurred by private investors, but by you the taxpayer.

What’s more, John explains, the regulations that are now being called for — particularly the so-called Volcker Rule — would not have prevented the losses since it would not have affected this transaction. Finally, John writes, the system worked as is. “JPMorgan Chase losses were not discovered by regulators; they were discovered by the bank itself conducting its own management reviews.”

What America is witnessing is the left using the news of JP Morgan’s bad judgment as an excuse for more government regulation. But as even Carney acknowledged, regulations “can’t prevent bad decisions from being made on Wall Street.”

It’s true that regulations “can’t prevent bad decisions”. But I’d go deeper. Regulations, on the other hand, can induce bad decisions.

Moral Hazard is when undue risks are taken because the costs are not borne by the party taking the risk. So when regulations and political actions (such as bailouts) rewards excessive risk taking, by having taxpayers shoulder the burden of the mistakes of the privileged parties like JP Morgan and other Too Big To Fail banks, then we should expect more of these.

At the Think Market Blog, Cato’s Jerry O’ Driscoll expounds further,

Reports indicate that senior management and the board of directors were aware of the trades and exercising oversight. The fact the losses were incurred anyway confirms what many of us have been arguing. Major financial institutions are at once very large and very complex. They are too large and too complex to manage. That is in part what beset Citigroup in the 2000s and now Morgan, which has been recognized as a well-managed institution.

If ordinary market forces were at work, these institutions would shrink to a size and level of complexity that is manageable. Ordinary market forces are not at work, however. As discussed on this site before, public policy rewards size (and the complexity that accompanies it). Major financial institutions know from experience they will be bailed out when they incur losses that threaten their surivival. Morgan’s losses do not appear to fall into that category, but they illustrate how bad incentives lead to bad outcomes.

Large financial institutions will continue taking on excessive risks so long as they know they can off-load the losses on taxpayers if needed. That is the policy summarized as “too big to fail.” Banks may be too big and complex to close immediately, but no institution is too big to fail. Failure means the stockholders and possibly the bondholders are wiped out. Until that discipline is reintroduced (having once existed), there will be more big financial bets going bad at these banks.

Saturday, May 05, 2012

Quote of the Day: Unintended Consequences of Regulations

Unregulated, a business’s reputation is its most valuable asset. A regulated business does not have the same problem, so long as it obeys the regulations. Regulations replace the overriding need for a business to protect its reputation, and it is no longer solely concerned for its customers: the rule book has precedence. And the more regulation replaces reputation, the less important customers become. Nowhere is this more obvious than in financial services…

The regulators assume the public are innocents in need of protection. They have set themselves up to be gamed by all manner of businesses intent on using and adapting the rules for their own benefits at the expense of their customers. These businesses lobby to change the rules over time to their own advantage and hide behind regulatory respectability, as clients of both MF Global and Bernie Madoff have found to their cost.

That’s from Alasdair Macleod at the GoldMoney.com

Friday, March 30, 2012

The Illusions of Technocracy

Professors Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson writes,

In 1979 Paul A. Volcker became chairman of the Fed and tamed inflation by raising interest rates and inducing a sharp recession. The more general lesson was simple: Move monetary policy further from the hands of politicians by delegating it to credible technocrats.

I hope the world operates in such simplicity. We just hire the right persons of virtue and intellect and our problems would vanish.

But that’s not the world we live in.

First of all, too much credit has been given to the actions of ex-US Federal Reserve chief Paul Volcker, who may just be at the right place at the right time.

Here is Dr. Marc Faber on Paul Volcker, (bold emphasis mine)

In the 1970s, the rate of inflation accelerated, partly because of easy monetary policies, which led to negative real interest rates, partly because of genuine shortages in a number of commodity markets, and partly because OPEC successfully managed to squeeze up oil prices. But by the late 1970s, the rise in commodity prices led to additional supplies and several commodities began to decline in price even before the then Fed chairman Paul Volcker tightened monetary conditions.

Similarly, soaring energy prices in the late 1970s led to an investment boom in the oil- and gas-producing industry, which increased oil production while at the same time the world learned how to use energy more efficiently. As a result, oil shortages gave way to an oil glut, which sent oil prices tumbling after 1985.

At the same time, the US consumption boom that had been engineered by Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s (driven by exploding budget deficits) began to attract a growing volume of cheap Asian imports, first from Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, and then, in the late 1980s, also from China.

I would therefore argue that even if Paul Volcker hadn't pursued an active monetary policy that was designed to curb inflation by pushing up interest rates dramatically in 1980/81, the rate of inflation around the world would have slowed down very considerably in the course of the 1980s, as commodity markets became glutted and highly competitive imports from Asia and Mexico began to put pressure on consumer product prices in the USA.

Then, markets had already been signaling the unsustainability of Fed induced inflation which had been underpinned by real market events as oversupply and globalization. Thus, Paul Volcker’s actions may have just reinforced an ongoing development.

In short, lady luck may have played a big role in Mr. Volcker’s alleged feat.

Next, looking at the world in a static frame misleads.

Conditions today are vastly dissimilar from the conditions then, as I recently wrote,

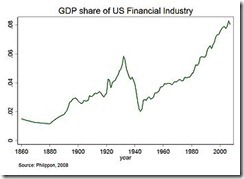

Circumstances during Mr. Volker’s time have immensely been different than today. There has been a vast deepening of financialization of the US economy where the share of US Financial industry to the GDP has soared. In short, the financial industry is more economically (thus politically) important today than in the Volcker days. Seen in a different prism, the central bank-banking cartel during the Volcker era has not been as embedded as today.

Yet how did this came about?

According to Federal Reserve of Dallas Harvey Rosenblum

Banks have grown larger in recent years because of artificial advantages, particularly the widespread belief that government will rescue the creditors of the biggest financial institutions. Human weakness will cause occasional market disruptions. Big banks backed by government turn these manageable episodes into catastrophes

Put differently, public policies or regulations spawn a feedback mechanism between regulators and the regulated through human interactions.

Laws and regulations don’t just alter the incentives of the market participants, they foster changes in the relationship between political authorities and the regulated industry.

More laws tend to increase or deepen the personal connections and communications between authorities and the regulated. This magnifies opportunities to leverage personal relationships where market participants seek concessions or compromises from their regulatory overseers, which leads to political favors, corruption, influence in shaping policies and the ‘captured’ regulators. And such relationships bring about the insider-outsider politics as evidenced by revolving door syndrome.

As human beings we live in a social world. The idea where “virtue” and knowledge are enough to shield political authorities from the influences of the regulated and or the political masters of public officials and or from personal ties, represents a world of ivory towers, and simply is fiction.

The true reason behind the illusions of technocracy as stated by Murray N. Rothbard, (bold emphasis added)

There are two essential roles for these assorted and proliferating technocrats and intellectuals: to weave apologies for the statist regime, and to help staff the interventionist bureaucracy and to plan the system.

The keys to any social or political movement are money, numbers, and ideas. The opinion-moulding classes, the technocrats and intellectuals supply the ideas, the propaganda, and the personnel to staff the new statist dispensation. The critical funding is supplied by figures in the power elite: various members of the wealthy or big business (usually corporate) classes. The very name "Rockefeller Republican" reflects this basic reality.

While big-business leaders and firms can be highly productive servants of consumers in a free-market economy, they are also, all too often, seekers after subsidies, contracts, privileges, or cartels furnished by big government. Often, too, business lobbyists and leaders are the sparkplugs for the statist, interventionist system.

What big businessmen get out of this unholy coalition on behalf of the super-state are subsidies and privileges from big government. What do intellectuals and opinion-moulders get out of it? An increasing number of cushy jobs in the bureaucracy, or in the government-subsidized sector, staffing the welfare-regulatory state, and apologizing for its policies, as well as propagandizing for them among the public. To put it bluntly, intellectuals, theorists, pundits, media elites, etc. get to live a life which they could not attain on the free market, but which they can gain at taxpayer expense--along with the social prestige that goes with the munificent grants and salaries.

This is not to deny that the intellectuals, therapists, media folk, et al., may be "sincere" ideologues and believers in the glorious coming age of egalitarian collectivism. Many of them are driven by the ancient Christian heresy, updated to secularist and New Age versions, of themselves as a cadre of Saints imposing upon the country and the world a communistic Kingdom of God on Earth.

Bottom line: Technocrats are no different than everyone else. They are human beings. They may have specialized knowledge covering certain areas of life, but they don’t have general expertise over the complex world of interacting human beings and of nature.

Technocrats have not been bestowed with omniscience enough to know and dictate on how we should live our lives. Instead, technocrats use their special ‘knowledge’ to advance their personal interests, by short circuiting market forces through politics, and who become tools for politicians or vested interest groups.

And that's why they are technocrats, they are afraid to put their knowledge to real tests by taking risks at the marketplace and rather hide behind the skirt of politics.

Thus, the idea of political efficacies from the philosopher king paradigm through modern day technocratic governance is a myth.

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

A Tale of Riches to Rags: The Bankruptcy of Former Irish Billionaire Sean Quinn

From BusinessWeek/Bloomberg:

Sean Quinn, once Ireland’s richest man, was declared bankrupt after losing more than one billion euros ($1.3 billion) investing in Anglo Irish Bank Corp.

Judge Elizabeth Dunne ruled on the bankruptcy in Ireland’s High Court in Dublin today. Quinn didn’t contest the bankruptcy petition brought by Irish Bank Resolution Corp., formerly Anglo Irish Bank.

The IBRC estimates that Quinn, whose fortune was valued at around $6 billion by Forbes magazine in 2008, owes the bank almost 2.9 billion euros. The lender in April appointed a share receiver to take over the Quinn family’s equity interest in Quinn Group, a conglomerate whose businesses included building materials, insurance and real estate.

We would see many bankruptcies by rich bankers when governments stop supporting them. But this isn’t likely to happen anytime soon as the welfare state will continue with its laborious efforts to preserve the current system.

And this can be seen with many "too big to fail" banks in the EU, continuing to receive massive support from their governments via the ECB.

Monday, December 12, 2011

Chart of the Day: Crony Capitalism

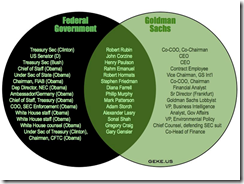

This fantastic Venn diagram from Professor Mario Rizzo shows of the conflict of interests, particularly the US government's revolving door relationship with the too big too fail, Goldman Sachs.

This also serves as a good example of regulatory capture or when a “regulatory agency created to act in the public interest instead advances the commercial or special interests that dominate the industry or sector it is charged with regulating” (Wikipedia.org).

Sunday, November 06, 2011

Gold Prices Climbs the Wall of Worry, Portends Higher Stock Markets

The Occupy Wall Street crowd sees this as a problem with capitalism. I believe that they are correct in their target, but wrong in their diagnosis. This is not a problem of capitalism since Wall Street is a practitioner of monetarism. A real capitalist system works through real intermediation creating positive opportunities for productive enterprises (scarce money is actually vital here). Our current system of repo-to-maturity and gold leasing is nothing but empty monetarism’s habit of regularly forcing the circulation of empty paper. And when the system begins to doubt itself, as it did in 2008, the answer is always about finding a way to restart the fractional maximization process yet again, which means disguising the real risks inherent to that process. There is no real mystery as to why prices and values have seen such a divergence, and why that is a big problem to a system that depends on appearances. Jeff Snider

Dramatic fluctuations out of the interminable nerve racking geopolitical developments continue to plague global financial markets.

Yet despite the seemingly dire outlook, major equity market bellwethers seem to be climbing the proverbial wall of worry.

The price trend of gold, for me, serves as a major barometer for the prospective direction of stock markets, aside from, as measure to the current state of monetary disorder.

Gold’s significant breakout beyond the 50-day moving averages implies that gold’s bull run have been intact and could reaccelerate going to the yearend.

Thus, rising gold prices should likely bode well for global stock markets.

Seasonal Bias Favors Gold, Gold Mining Issues and Stock Markets

It is important to point out that gold’s statistical correlation with global stock markets may not be foolproof and or consistently reliable as they oscillate overtime. In addition, gold has no direct causal relationship with stock markets.

From a causal realist standpoint, the actions of gold prices shares the same etiological symptoms with stock markets—they function as lighting rod to excessive liquidity unleashed by central banks looking to ease financial conditions for political goals.

As shown above, all three major bellwethers of the US S&P 500 (SPX), China’s Shanghai index (SSEC) and the Euro Stox 50 (STOX50) seem to be in a recovery mode. This in spite of last week’s still lingering crisis at the Eurozone.

While I may not be a votary of statistically based metrics, seasonal patterns, mostly influenced by demand changes based on cultural factors, could have significant effects when other variables become passive.

In terms of gold prices, higher demand for jewelries from annual holiday religious celebrations, e.g. India’s Diwali and the wedding season, Christmas Holidays and preparations for China’s 2012 New Year of the Dragon[1], has statistically produced positive and the best returns of the year.

‘Statistical’ bias for a yearend rally in gold mining stocks (see lower right window) reveals that monthly returns for November has the largest gain of the year, with a potential follow through to December.

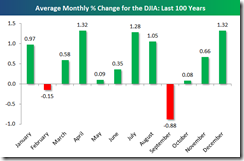

In addition, the stock market also has a seasonal ‘statistical’ flavoring with a potential yearend rally supported by additional gains from the first quarter as shown in the above chart by Bespoke Invest using the Dow Jones Industrials computed over 100 years in 2010[2]

Distinctions in the monthly returns involves many factors such as the tax milestones, quarterly "earnings season", "window-dressing" on the part of fund managers, index-rebalancing periods or many more[3] but these should never be seen as fixed variables as conditions ceaselessly changes.

Again statistics only measures and interprets history, but most importantly statistics does not take in consideration the actual operations of prospective human actions[4]. For instance, statistics can’t tell if policymakers will raise interest rates or hike taxes or print money and their potential effect on the markets.

Deeply Entrenched Bailout Policies—Globally

Nevertheless, given the current political climate, gold prices will mainly be driven by changes in the political environment. Seasonal effects will most likely be enhanced by political factors than the other way around.

In China, policymakers have reportedly been shifting towards an easing stance meant to address the current funding squeeze being encountered by small businesses.

Lending quotas of some China’s banks have reportedly been increased, where new lending may exceed 600 billion yuan ($94 billion) this month from 470 billion in September reports the Bloomberg[5].

These actions could have been driving the current recovery of the China’s Shanghai Index.

In Greece, political impasse has reportedly forced Greece Prime Minister George Papandreou to call for a referendum which initially rattled global financial markets[6].

In reality, Mr. Papandreou’s ploy looks like a brilliantly calculated move resonant of Pontius Pilate’s washing of his hand on the execution of Jesus Christ[7].

Given the recent poll results[8] which shows that the Greeks have not been favorable to government’s austerity reforms or bailouts but have also exhibited fervid reluctance to exit from the Eurozone (since Greeks has been benefiting from Germans), PM Papandreou saw the opportunity to absolve himself by tossing the self-contradictory predicament for the public to decide on.

In addition, realizing the potential risks, Germany’s Angela Merkel and France’s Nicolas Sarkozy interceded to prevent a referendum from happening, which I suppose could also be part of PM Papandreou’s tactical maneuver.

From these accounts, a vote of confidence over PM Papandreou’s government was held instead, where by a slim margin, PM Papandreou prevailed. The parliamentary victory thus empowers him to reorganize and consolidate power through a supposed Unity government[9].

In Italy, popular protests have been mounting against Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi supposedly for his failure to convince investors and European allies that Italy can trim the Euro-region’s second biggest debt, which saw the Italy’s 10 year bond spiked to record high 6.4% on Friday[10].

PM Berlusconi recently rejected an offer of aid from the IMF, but instead, requested the multilateral institution to monitor her debt cutting efforts.

Yet given the current political maelstrom, European Central Bank (ECB) president Mario Draghi, who is also an alumnus of Goldman Sachs and who has just recently assumed office from Jean Claude Trichet surprised the financial markets with an interest rate cut citing risks of a Greece exit from the EU and from an economic slowdown brought about by the current financial turmoil[11].

Mr. Draghi’s actions seems like a compromise to the Global Banking cartel[12] where the latter has clamored for the ECB to backstop the bond markets by active interventions through quantitative easing (QE).

Obnoxious partisan politics seem to have provided a veil or an excuse for the ECB’s widening use of her printing press.

Yet ironically, attempts to portray the ECB as imposing disciplinary measures[13] on profligate crisis affected governments seem like a comic skit in the Eurozone’s absurd political theatre. The public is being made to believe that one branch of government intends to provide check and balance against the other.

In truth, the Euro-bank bailouts reallocates the distribution or transfers resources from the welfare government to the ECB and the Banking cartel in the hope that by rescuing banks, who functions as the major conduit in providing access to funds for governments, the welfare state will eventually be saved.

Yet instead of a check and balance, both the ECB and EU governments have been in collusion against EU taxpayers and EU consumers, to preserve a fragile an archaic government system that seems in a trajectory headed for a collapse.

The ECB’s asset purchases (upper right window) have been driving up money supply (upper left window) even as the EU’s economy seems faced with growing risks of recession—as evidenced by floundering credit growth in the EU zone. Yet contrary to Keynesians obsessed with the fallacious liquidity trap theory, inflation rate has remained obstinately above government’s targets which allude to the increasing risks of stagflation for the EU.

And further increases in inflation rates will ultimately be reflected and vented on the bond or the interest rate markets. These should put to risk both the complicit governments and their beleaguered financiers—the politically privileged banking system backed by the central banks—whom are all hocked to the eyeballs. Rising interest rates likewise means two aspects, dearth of supply of savings and diminishing the potency of the printing press. Yet to insist in using the latter option means playing with fires of hyperinflation.

And like in the US, the welfare warfare states have continuously been engaging in policies that would signify as digging themselves deeper into a hole.

Proof?

Inflationism as Cover to the Derivatives Trigger

It’s also very important to point out anew[14] that the US banking and financial system are vastly susceptible to the developments in the Eurozone. In short, US financial system has been profoundly interconnected or interrelated with the Euro’s financial system

Exposure of US banks to holders of Greek, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish and Italian debt in the first semester of 2011 has jumped by $80.7 billion to $518 billion mostly through credit default swaps where counterparty risks from a default could ripple through the US banking sector.

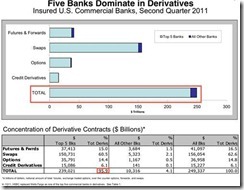

Yet about 97% of the US derivative exposure has been underwritten by JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America Corp. and Citigroup Inc. The estimated total net exposure by the five government protected “too big too fail” banks to the crisis affected PIIGS are at measly $45 billion.

However, part of the hedging strategy by these banks and other financial institutions have been to buy credit insurance or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) of their counterparties which have not been included as part of these estimates. In addition, counterparties have not been clearly identified.

Because of this, European leaders have reportedly been extremely sensitive as not to trigger default clauses in CDS contracts that may put banks across two continents at risk.

Ironically, the institution that decides on whether debt restructuring triggers CDS payments, the International Swaps & Derivatives Association, or the ISDA, has these biggest government’s cartelized private banks sitting on the company’s boards.

So the big 5 essentially calls the shots in the derivatives markets or on when default clauses are triggered and when it is not.

At the end of the day, this eye-catching quote from the Bloomberg article[15] from which most of the discussion have been based on, seems to capture the essence of the policy direction today’s political system

U.S. banks are probably betting that the European Union will also rescue its lenders, said Daniel Alpert, managing partner at Westwood Capital LLC, a New York investment bank.

“There’s a firewall for the U.S. banks when it comes to this CDS risk,” Alpert said. “That’s the EU banks being bailed out by their governments.”

The point to drive at is that both governments, most likely through their respective central banks, will continue to engage in serial massive bailout policies to avert a possible banking sector meltdown from an implosion in derivatives.

Such dynamics lights up the fuse that should propel gold prices to head skyward. And the consequent massive infusion of monetary liquidity will only buoy global stock markets higher, for as long as inflation rates remain constrained for the time being.

Remember, central banks have used stock markets as part of their tool kit to manipulate the “animal spirits”[16] from which they see as a key source of economic multiplier from the misleading spending based theory known as the “wealth effect”, a theory that justifies crony capitalist policies.

Policies that have partly been targeted at the stock market and mostly at the preservation of the current unsustainable political system are being funneled into gold and reflected on its prices, which has stood as an unintended main beneficiary from such collective political madness.

Yet rising gold prices shows the way for the stock markets until the inflation rates hurt the latter. But again, not all equity securities are the equal.

I would take the current windows of opportunities to accumulate.

[1] Holmes Frank Investor Alert - 3 Drivers, 2 Months, 1 Gold Rally?, November 4, 2011, US Global Investors

[2] Bespoke Invest Seasonality Does Not Favor Stock Investments In February, February 1, 2011 Decodingwallstreet.blogspot.com

[3] Stockwarrants.com Seasonality

[4] See Flaws of Economic Models: Differentiating Social Sciences from Natural Sciences, November 3, 2011

[5] Bloomberg.com China Easing Loan Quotas May Cut Economic Risks, Daiwa Says, November 4, 2011

[6] See The Swiftly Unfolding Political Drama in Greece, November 2, 2011

[7] Wiipedia.org Pontius Pilate

[8] Craig Roberts, Paul Western Democracy: A Farce and a Sham, November 4, 2011, Lew Rockwell.com “A poll for a Greek newspaper indicates that whereas 46% oppose the bailout, 70% favor staying in the EU, which the Greeks see as a life or death issue.”

[9] See Greece PM Papandreou Wins Vote of Confidence, November 5, 2011

[10] Bloomberg.com Thousands Rally in Rome, Pressing Italy’s Berlusconi to Resign Amid Crisis, November 6, 2011

[11] See ECB’s Mario Draghi’s Baptism of Fire: Surprise Interest Rate Cut, November 4, 2011

[12] See Banking Cartel Pressures ECB to Expand QE, November 3, 2011

[13] Reuters Canada ECB debates ending Italy bond buys if reforms don't come, November 5, 2011

[14] See US Banks are Exposed to the Euro Debt Crisis, October 8, 2011

[15] Bloomberg.com Selling More CDS on Europe Debt Raises Risk for U.S. Banks, November 1, 2011

[16] See US Stock Markets and Animal Spirits Targeted Policies, July 21, 2010

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Chart of the Day: Cartelization of the US Banking System

Hat tip Karen De Coster at Lew Rockwell Blog

Click on the image to enlarge

This germane quote from the great Murray N. Rothbard tells us why too big to fail banks is the direction of central banking policies,

The fewer the number of competing banks in existence, the easier it will be to coordinate rates of expansion. If there are many thousands of banks, on the other hand, coordination will become very difficult and a cartel agreement is apt to break down

Monday, September 26, 2011

US Derivative Time Bomb: Five Banks Account for 96% Of The $250 Trillion Exposure

From Zero Hedge (bold emphasis mine)

The latest quarterly report from the Office Of the Currency Comptroller is out and as usual it presents in a crisp, clear and very much glaring format the fact that the top 4 banks in the US now account for a massively disproportionate amount of the derivative risk in the financial system. Specifically, of the $250 trillion in gross notional amount of derivative contracts outstanding (consisting of Interest Rate, FX, Equity Contracts, Commodity and CDS) among the Top 25 commercial banks (a number that swells to $333 trillion when looking at the Top 25 Bank Holding Companies), a mere 5 banks (and really 4) account for 95.9% of all derivative exposure (HSBC replaced Wells as the Top 5th bank, which at $3.9 trillion in derivative exposure is a distant place from #4 Goldman with $47.7 trillion). The top 4 banks: JPM with $78.1 trillion in exposure, Citi with $56 trillion, Bank of America with $53 trillion and Goldman with $48 trillion, account for 94.4% of total exposure. As historically has been the case, the bulk of consolidated exposure is in Interest Rate swaps ($204.6 trillion), followed by FX ($26.5TR), CDS ($15.2 trillion), and Equity and Commodity with $1.6 and $1.4 trillion, respectively. And that's your definition of Too Big To Fail right there: the biggest banks are not only getting bigger, but their risk exposure is now at a new all time high and up $5.3 trillion from Q1 as they have to risk ever more in the derivatives market to generate that incremental penny of return.

At this point the economist PhD readers will scream: "this is total BS - after all you have bilateral netting which eliminates net bank exposure almost entirely."

True: that is precisely what the OCC will say too. As the chart below shows, according to the chief regulator of the derivative space in Q2 netting benefits amounted to an almost record 90.8% of gross exposure, so while seemingly massive, those XXX trillion numbers are really quite, quite small... Right?

...Wrong. The problem with bilateral netting is that it is based on one massively flawed assumption, namely that in an orderly collapse all derivative contracts will be honored by the issuing bank (in this case the company that has sold the protection, and which the buyer of protection hopes will offset the protection it in turn has sold). The best example of how the flaw behind bilateral netting almost destroyed the system is AIG: the insurance company was hours away from making trillions of derivative contracts worthless if it were to implode, leaving all those who had bought protection from the firm worthless, a contingency only Goldman hedged by buying protection on AIG. And while the argument can further be extended that in bankruptcy a perfectly netted bankrupt entity would make someone else whole on claims they have written, this is not true, as the bankrupt estate will pursue 100 cent recovery on its claims even under Chapter 11, while claims the estate had written end up as General Unsecured Claims which as Lehman has demonstrated will collect 20 cents on the dollar if they are lucky.

The point of this detour being that if any of these four banks fails, the repercussions would be disastrous. And no, Frank Dodd's bank "resolution" provision would do absolutely nothing to prevent an epic systemic collapse.

...

Lastly, and tangentially on a topic that recently has gotten much prominent attention in the media, we present the exposure by product for the biggest commercial banks. Of particular note is that while virtually every single bank has a preponderance of its derivative exposure in the form of plain vanilla IR swaps (on average accounting for more than 80% of total), Morgan Stanley, and specifically its Utah-based commercial bank Morgan Stanley Bank NA, has almost exclusively all of its exposure tied in with the far riskier FX contracts, or 98.3% of the total $1.793 trillion. For a bank with no deposit buffer, and which has massive exposure to European banks regardless of how hard management and various other banks scramble to defend Morgan Stanley, the fact that it has such an abnormal amount of exposure (but, but, it is "bilaterally netted" we can just hear Dick Bove screaming on Monday) to the ridiculously volatile FX space should perhaps raise some further eyebrows...

Such immense risk exposure by ‘Too Big to Fail’ (TBTF) US banks entail that political actions or policy making will likely be directed towards the prevention of a massive deflationary banking sector collapse from a derivatives meltdown.

And problems at the Eurozone could just be the pin that could ‘pop the bubble’.

This implies greater likelihood of persistent bailout policies which mostly will be coursed through inflationism. It’s an “inflate or die” for politically privileged TBTF banks in the US or in the Eurozone.

Again political leaders appear to be using the financial markets as leverage to negotiate for the passage of such policies.

Proof?

From today’s Bloomberg article, (bold emphasis mine)

U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner warned at the annual meeting of the IMF failure to combat the Greek-led turmoil threatened “cascading default, bank runs and catastrophic risk.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel said euro-region leaders must erect a firewall around Greece to avert a cascade of market attacks on other European states that would risk breaking up the currency area.

Expanding the powers of the region’s rescue fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, as agreed by European leaders in July is necessary to avoid Greece’s problems from spilling over to other countries, Merkel said late yesterday on ARD television. The fund’s permanent successor, due to take effect in mid-2013, is needed “so we can in fact let a state go insolvent” if it can’t pay its bills, she said.

Policy makers can make the EFSF more “efficient” by leveraging it without involving the ECB, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble said over the weekend. He also raised the prospect of bringing in the permanent backstop before 2013.

Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney estimated 1 trillion euros ($1.3 trillion) may have to be deployed while U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said a solution is needed by the time that Group of 20 leaders meet in Cannes, France, on Nov. 3-4.

Policymakers have been intensifying their jawboning or mind conditioning of the public of the exigencies of more bailouts.

They will come. But, perhaps, only after the markets endure more pain.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Quote of the Day: Path Dependency

From Professor Arnold Kling,

…most respectable people think that Bernanke and Paulson and TARP and such SAVED THE WORLD, and so that is now the model going forward for handling any situation involving shaky large banks.

Tuesday, July 06, 2010

Japan’s Lost Decade Wasn’t Due To Deflation But Stagnation From Massive Interventionism

Many of you may be familiar with the idiom to “fit a square peg to a round hole”. This simply means, according the Free dictionary, “trying to combine two things that do not belong or fit together.”

From Oftwominds.com

I think this expediently characterizes mainstream’s misplaced notion about Japan’s long held predicament: deflation.

Because of the mammoth boom-bust cycle seen in Japan's property and stock markets, which led to Japan’s economic “lost decade”, the image of the Great Depression of the 1930s has frequently been conjured or extrapolated as the modern version for it.

Of course, there is a second major reason for this, and it has been ideologically rooted, i.e. the bubble bust has been used as an opportunity to justify the imposition of theoretical fixes by means of more interventionism.

Has a deflationary depression blighted Japan?

If the deflation is measured in what mainstream sees as changes in the price level of the consumer price index, then the answer is apparently a NO.

As you would notice from the graph from moneyandmarkets.com, deflation isn’t only episodic (or not sustained), but likewise Japan’s intermittent economic growth (blue bars) came amidst the backdrop of negative or almost negative CPI (red line)! In other words, economic growth picked up when prices where in deflation--this translates to real growth.

And if measured in terms of changes in monetary aggregates, then obviously given that the changes in Japan's M2 has been steadily positive, as shown by the chart above from Northern Trust, all throughout the lost decade, then we can rule out a "monetary deflation".

Of course, the next easiest thing for the mainstream to do is to pin the blame on credit growth.

chart from McKinsey Quarterly

While there is some grain of truth to this, this view isn’t complete. It doesn’t show whether the lack of credit growth has been mainly from demand or supply based. It doesn't even reveal why this came about.

We can even say that such generalizations signify as fallacy of division. Why? Because the problem with macro analysis is almost always predicated on heuristics-or the oversimplification of variables involved in the analytic process.

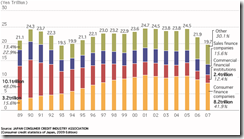

Banks have not been the sole source of Japan’s ‘credit’ market. In fact, there are many as shown below.

``Providing credit to consumers is generally referred to as "consumer credit." This can be classified into two types. The first is providing credit to allow consumers to buy specific goods and services, which is called "sales on financing," and the second is providing credit in cash, which is called "consumer finance." There are many types of financial service companies that offer consumer finance, including banks, but compenies which specialize in providing small loans to consumers are referred to as "consumer finance companies."

Further promise.co.jp describes the function of consumer finance companies as providing credit

``including loans but, unlike banks, do not take deposits are referred to as "non-banks." Leasing companies, installment sales finance enterprises, credit card companies, and consumer finance enterprises belong to the non-bank category.”

So how has Japan’s alternative financing companies performed during the lost decade?

1) During the lost decade or from 1989-2007, the share of consumer financing companies (yellow-orange bar) has exploded from 15.6% to 41.9%!

2) Other forms of credit (apple green bar) also jumped from 13.4% to 30.1% during the same period.

3) The bubble bust has patently shriveled the share of 'traditional bank' based lending or the share of lending from commercial financial institutions collapsed from 48% to 12.4%.

4) The sales financing companies likewise lost some ground from 22.4% to today’s 15.6%.

All these reveals that while it is true that nominal or gross lending has declined, there has been a structural shift in the concentration of lending activities mainly from the banking to consumer financing companies and "other" sources.

And importantly, it disproves the idea that Japanese consumers have “dropped dead” or that the decline in lending has been from the demand side.

Obviously banks were hampered by the losses stemming from the bubble bust. But this wasn’t all, government meddling in terms of bailouts were partly responsible, as we wrote in 2008 Short Lessons from the Fall of Japan

``One, affected companies or industries which seek shelter from the government are likely to underperform simply because like in the Japan experience, productive capital won’t be allowed to flow where it is needed.

``Thus, the unproductive use of capital in shoring up those affected by today's crisis will likely reduce any industry or company’s capacity to hurdle its cost of capital.

``Two, since capital always looks for net positive returns then obviously capital flows are likely to go into sectors that aren't hampered by cost of capital issues from government intervention.

``This probably means a NEW market leadership (sectoral) and or money flows OUTSIDE the US or from markets/economies heavily impacted by the crisis.”

Apparently, our observation was correct, the new leadership had shifted to the financing companies.

But there is more.

Because the banking system had been immobilized, which conspicuously tightened credit access, the explosive growth of the financing companies emerged as result of demand looking for alternative sources of supply.

In addition, financing companies, who saw these opportunities circumvented tight regulations or resorted to regulatory arbitrage, in order to fulfill this role.

According to the Federal Bank of San Franscisco, (bold emphasis mine)

``Prior to the passage of the new legislation, Japan had two laws restricting consumer loan interest rates. The Interest Rate Restriction Law of 1954 set lending rates based on the size of the loan, with a maximum rate of 20 percent. The Investment Deposit Interest Rate Law, last amended in 2000, capped interest rates on consumer loans at 29.2 percent on the condition that any rate exceeding 20 percent requires the written consent of the borrower. Most Japanese CFCs have been operating in this “gray zone” of interest rates, charging rates between 20 and 29.2 percent.

``Non-bank consumer finance companies in Japan comprise a ¥20 trillion industry, averaging 4 percent annual loan growth over the past decade while bank loan growth was negative. Most of the approximately 14,000 registered lenders are small, with the largest seven operators-which include the consumer finance arms of GE Capital and Citigroup- having a 70 percent market share. The significant growth in this industry can be traced directly to the collapse of the asset bubble in the early 1990s when consumers whose collateral had dwindled in value turned to CFCs offering uncollateralized loans. Adding to the success of the industry was the fact that CFCs were more service-oriented than the retail operations of Japanese banks, offering a wider network of loan offices, 24-hour loan ATMs, and faster credit approval.”

In short, banking regulations and policies proved to be an important obstacle to credit access.

Yet, the Japanese government worked to rehabilitate on these legal loop holes. This led to further restrictions to credit access.

According to Yuki Allyson Honjo, Senior Vice President, Fox-Pitt Kelton (Asia), [bold emphasis mine]

``The Supreme Court made a ruling in 2006 to make it easier for individuals to collect repayment of interest in excess of that allowed under the Interest Rate Restriction Law (grey zone interest). The court ruling called into question the legality of the grey zone. This prompted revisiting of the rules governing money lending and forced companies to create grey zone reserves. People were entitled to claim the "extra" interest they paid from their lenders.

``Revisions to the money lending laws were passed, and by June 2010, the maximum lending rate will be unified to rates specified under the Interest Rate Restriction Law, thereby eliminating the grey zone. Loans will be limited to a third of borrowers' annual income. For loans exceeding 1 million yen, moneylenders would be obligated to inquire about the applicant's annual income. Implementation is still ambiguous. Regulators are to have more power, such as the ability to issue business improvement orders.

``The rate decline held various consequences for the industry. Margins were lowered as lenders were forced to lower their lending rates. There was a reduction in volume, with loans to current borrowers no longer being profitable, some customers were deemed too high-risk to borrow at the lower rates. Customers could borrow less due to new legislation restricting total loans as a percentage of income. Also, there has been a rise in write-offs.

``The result of all of this is that the number of registered money lenders has dropped precipitously since regulation began in 1984. The loan market is an oligopoly with 60% of the total loan balance with the Big Four, and 90% percent with the top 25 firms. This oligopoly was created in reaction to regulation.

``Stock prices for money lending companies began to drop steadily in 2006, predating the current economic crisis. The necessity for grey zone reserves has caused problems in money lenders' balance sheets. In March 2007, there are many large negative numbers visible in the balance sheets of Aiful, Takefuji, Acom and Promise. Loans approval rates crashed around 2006, with Aiful only accepting 7% of loans recently, down from over 50% before the 2006 Supreme Court rulings. Every month, 25-30 billion yen is paid out by money lenders to customers in grey zone claims, increasing steadily since 2006. Grey zone refunds have begun to pick up recently as a result of the recent economic crisis.

``The consequences of the court ruling and the re-regulation are that the Big Four companies found direct funding difficult. Credit default swaps have increased dramatically for Takefuji and Aiful, who are now essentially priced to fail. Bond yields also increased and going to market is difficult for these companies.

``From the regulator's perspective, re-regulation has been largely a success, given their aims. The size of the industry and the number of players have been reduced. The government has greater control on the industry and over-borrowing has been reduced. In regard to this last goal, its success is unclear as black market statistics are not reliable. In fact, anecdotes suggest that black market lending demand has increased.”

So aside the aftermath bubble bust, the bailouts of zombie institutions and taxes we discovered that government diktat have been the instrumental cause of supply-side impairments in Japan's credit industry.

Moreover, the other consequences has been to restrain competition by limiting the number of firms which led to the persistence of high unemployment rates, and fostered too-big-to-fail "oligopolies" institutions.

So we can conclude two things:

1. Japan’s economic malaise hasn’t been about deflation but about stagnation from wrong policies.

2. The weakness in Japan’s credit growth essentially has also not been about liquidity preference and the attendant liquidity trap, or the contest between capital and labor, or about subdued aggregate demand, but these has been mostly about the manifestations of the unintended consequences of the Japanese government's excessive interventionism.

As Ludwig von Mises wrote,

``The various measures, by which interventionism tries to direct business, cannot achieve the aims its honest advocates are seeking by their application. Interventionist measures lead to conditions which, from the standpoint of those who recommend them, are actually less desirable than those they are designed to alleviate. They create unemployment, depression, monopoly, distress. They may make a few people richer, but they make all others poorer and less satisfied.”

And it is here that we see how the mainstream can't seem to fit the square peg (deflation) to the round hole (stagnation).