"Reason obeys itself; and ignorance does whatever is dictated to it."- Thomas Paine

Does “Sell in May” Apply in the Era of Activist Central Banking?

“Sell in May and go away” has been a popular Wall Street axiom that has been premised on the seasonal, particularly semestral, effects of stock market performance. Some people use this as their portfolio management strategy. The idea is to avoid the sharp downside volatility which periodically besets the equity markets during September and October and to reposition back on November. So basically the strategy entails a semi-annual exposure on the stock markets. Such approach suites people who trade the market over the short-term. Besides given the short term nature of stockmarket investing this should benefit brokers more rather than real investors.

But like any patterns, they can be defective. Investopedia.com rightly notes of its supposed drawback[1], “market timing and seasonality strategies do not always work out, and the actual results may be very different from the theoretical ones.”

The answer to this is simple: history hardly functions as reliable indicators of the future.

In today’s environment where central bank policies increasingly determine the direction of asset prices, comparing with previous accounts would most likely be rendered inapplicable or irrelevant. That’s because in the past, markets has had more freedom or has significantly been less intervened with. Current direction has been towards more interventions, thereby more distortions.

Multiple accounts of Parallel universe or flagrant disconnect between financial markets and the real economies have been the hallmark of the era of activist central banking. Current global market conditions have been operating on uncharted territories.

The same operating principle applies to the Philippine financial markets too.

The Moody’s “No Property Bubble” Redux

The domestic markets have been seduced by easy money policies, particularly zero bound rates, which the consensus interprets as “sustainable”. The allure of easy money policies has also been reflected on current populist political dynamics.

Without looking under the hood, and by imbuing hook, line and sinker the blandishments by the mainstream media, the politicians and vested interest groups, the markets have unduly embraced the “This Time is Different” outlook.

New order thinking such as “The Rising Star of Asia” and the latest defense of “No Property Bubble” both of which emanates from the US credit rating agency Moody’s are wonderful examples.

Moody’s “No property bubble” defense has mainly been a narrative of the reclassification of the real estate loans (REL) statistics from the local central bank, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ (BSP) and an expression of steadfast faith on the same institution. The Moody’s expert who preaches on the use of economics then confuses statistics with economics[2].

Their analysis apparently fails to adhere to the lessons of history; an explosion of world banking crisis had been largely due to the inflationist policies by central banks undergirded by the paper money system. Incidences of banking crises ballooned after the closing of the Bretton Woods gold exchange standard in 1970 or the Nixon Shock.

Central banks and governments find inflationism as convenient instruments to promote political objectives which results to an eventual blowback. Hence the boom bust cycles.

Yet officials of the Moody’s hardly see the one of the most important factors in identifying bubbles: the trajectory.

At the current rate of growth, debt levels will proximate if not surpass the 1997 high by end of this year. The big bosses of the BSP discount or dismiss such risks because they use neighboring debt levels to compare with.

For instance it would be easy to dismiss the risks of debt when domestic debt can be seen as vastly smaller than the regional counterparts (see upper window[3], this chart will be used also in my discussion of Abenomics).

Yet such apples and oranges comparison has been predicated on the false assumption that the operating frameworks of the political economies of the region are similar. From culture, to political institutions, to degree of market environment, there are hardly any material similarities. And like individuals, each country has a distinctive thumbprint. So relative comparisons should only be based on accounts of high degrees of similarities which should be rare.

And as history has shown and previously discussed[4], there is no line in the sand for a credit event to happen (lower window). For instance, credit events occurred in India, Korea and Turkey (1978) even when the external debt ratio had been low by debt standards.

In short, all countries have unique levels of debt intolerance.

Aside from the trajectory, another very important pillar which has been overlooked is the incentives that drive the trajectory. Zero bound rates have increased appetite for debt accumulation from both the private sector and the government. Credit rating upgrades also reward debt. Thus zero bound rates which prompts for yield chasing speculations through debt accretion will be compounded by credit upgrades.

The feedback loop in the yield chasing dynamics from credit easing policies has been evident even in the US. Rising prices feeds into mounting debt and vice versa. In terms of margin debt, as of April this year, NYSE’s margin debt at $384,370 has eclipsed the 2007 July high of $381,370 as US equity markets reach a milestone[5].

Zero bound rates and credit upgrades will also serve as incentive for the government to spend more by borrowing more. So both the public and private sectors’ increasing debt exposure comes in the expectations that the regime of low interest rates have become a permanent feature.

Additionally, statistics can be distorted. For instance, today’s vigorous statistical economic growth has been magnified by a credit boom which effectively shrinks debt ratios. Unknown to most, once the boom reverse, such ratio will explode to the upside. This will be compounded by “automatic stabilizers” or technical gobbledygook for government rescues or bailouts which will be allegedly used to provide “cushion” to an economic downturn but in reality benefit the politically favored.

We don’t even have a crisis but current policies have already been calibrated towards a crisis fighting mode from both the fiscal and monetary policy fronts.

Aside from record low interest rates, on the fiscal front, the Philippine government’s budget deficit[6], according to a recent report, will more than double in the first half of this year (Php 84.66 billion) compared to the same period from last year or 2012 (Php 34.5 billion) as growth in expenditures (18.9%) outweighs the growth in revenue collection (13.16%).

So how will this be funded? Naturally, by debt. What the heck are low interest rates for???!!!

So Moody’s does not see or refuses to look or simply denies the causal link between the incentives from such policies and its effect on the markets. Yet we seem to be witnessing both the government and the private sector in a debt financed spending splurge.

No matter, denials will not wish away existing problems.

As an analogy, a man ignores the risks of having to swim in an open sea with a fresh wound. Somewhere he finds himself being encircled or surrounded by sharks. Experts from Moody’s would probably make a risk assessment by identifying the shark/s and cite statistics showing the world incidences of shark attacks[7] from such specie/s, as well as, the history of local occurrence, the time of the day, water temperatures and many more, to compute for the statistical odds. Using this information plus since the sharks have not made any aggressive move yet, Moody’s will likely declare “No Shark Attack risks”.

Meanwhile common sense should suggest that a shark attack seems imminent for one basic reason: sharks smell food from the blood emitted by the man’s wound, which is the reason they are sizing up the man through encirclement passes and awaits the opportunity to pounce on him. So the man has to act to immediately by finding a way how to defend himself or work to cover on his injury, rather than just float, relax and enjoy the presence of what seems as ambling water predators.

Such is the stark difference between the use of statistical logic which predominates on the consensus mindset and the causal realist[8] reasoning.

And such also reveals of how the bubble mentality works. The appeal to statistics functions like a mental opiate that reinforces the Panglossian view that artificial booms will everlastingly blossom.

Global stock markets have been under pressure last week, mostly due to the tremors from “Abenomics”.

But for the Philippine markets, there seems to be no such thing as risks from “Abenomics” or anything in the horizon.

This comes from the marketplace whose convictions have become entrenched that there is no way but up, up and away! This applies to politically correct themes. On the other hand, politically incorrect themes have been seen as perpetually condemned.

As analyst Sean Corrigan neatly describes the illusions from groupthink[9]

Even if the monetary fuel for this whirl of self-reinforcement is not lacking, the market still needs a narrative around which it can cluster psychologically. It needs a canon of shared myth about which the bard can weave a reassuringly familiar refrain so as to reinforce the sense of community when the members of the clan gather to listen to his warblings amid the flickering fires and guttering torchlight of the Great Hall at night

Nonetheless, this week has been a rerun of last week. Strong start, soft finish.

At the end of the day, the Phisix still closed at essentially record highs, off by only a fraction.

Deep convictions will only be undermined when a big unexpected event is enough to jolt back senses to reality.

Abenomics in Hot Water!

The bubble outlook has not just really been about the Philippines. Such manic character has assumed a global presence.

The intensifying use of “something for nothing” policies, promoted by media, vested interest groups, the political class and their allies, has surely been getting a lot of fans particularly from the short term oriented and yield chasing crowd as shown by buoyant markets.

One strong statistical growth data from “Abenomics” has been enough to merit a magazine cover from the Economist[10] depicting Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe more than a rock star but a superhero! And I’ve encountered studies and articles with headlines: “Abenomics Works!” or “Abenomics is the only thing!”.

Yet magazine covers can occasionally serve as useful indicators of extreme sentiments, a crowded trade or major inflection points of markets.

The ruckus over at Japan’s bond markets last Thursday which prompted for a one day crash in Japan’s stock market has been rationalized by media as having been spooked by US Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s comments[11].

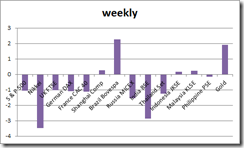

Thursday, the key Japanese benchmark Nikkei tanked by 7.3% (upper window) while the Topix dived by 6.9%.

But such imputation has hardly been accurate. Yields of Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) have surged since the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) announcement of the doubling of her monetary base, during the first week of April. The BoJ will incorporate buying assets to the tune of ¥ 7.5 trillion ($78.6 billion) a month[12]. Later this has been revised to ¥7 trillion ($71.41 billion)[13].

One would note that despite the huge interventions by the Bank of Japan last Thursday and Friday which brought down the 10 year yield to 1% to .82%, yields across the curve[14] except the 2 year remains significantly up over the month.

This means that if there has been any influence from Bernanke’s threat to withdraw stimulus such served as aggravating circumstance.

Mainstream media immediately downplayed the role played by the marginal decline by US stocks in response to the Japan rout.

Media instead shifted the blame on China’s manufacturing contraction. Just look at the headlines on the day following the Japan crash: From Bloomberg “U.S. Stocks Retreat on China Data, Stimulus Speculation[15]” and from BBC “Global stocks markets hit after Chinese data and Fed comments[16]”.

Look at the earlier chart showing China’s PMI. Following a brief jump during the late 2012, the HSBC Purchasing Managers Index turned the corner late 2012 and has been on a DECLINE through this year. Thus the downshifting trend shouldn’t have been seen as a surprise. Falling commodity prices also has partly been reflecting on such dynamic.

The real shocker has been Japan’s twin stock market and bond market crash which clearly had been a “fat tail” event considering the parabolic surge of Japan’s equity markets. Importantly such dramatic ascent has been due to the cheer leading and heavy evangelism by media in support of Abenomics.

In short, for the consensus, Abenomics can take no blame. Japan’s financial market crash has essentially been whitewashed!

Nevertheless Abenomics is in hot water.

Abenomics: Digging Japan Deeper into the Hole

Deliberate disinformation or not, the current convulsions of the Japanese markets proves my earlier point[17]:

Abenomics operates in a logical self-contradiction. While the politically and publicly stated desire has been to ignite some price inflation, Abenomics or aggressive credit and monetary expansion works in the principle that past performance will produce the same outcome or the that inflationism will unlikely have an adverse impact on interest rates, or that zero bound rates will always prevail.

The idea that unlimited money printing will hardly impact the bond markets is a sign of pretentiousness.

But there seems to be a more important reason behind Abenomics; specifically, the Bank of Japan’s increasing role as buyer of last resort through debt monetization in order to finance the increasingly insatiable and desperate government.

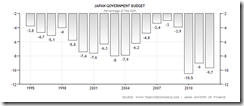

First of all considering a political economy whose debt is 24 times (see first chart) central government tax revenues[18], this makes Japan ultra-sensitive to interest rate risks and subsequently rollerover and credit risks.

Since inflationism represents a transfer from creditor to the borrower, or a subsidy to the borrower at the expense of the saver, the prospects of higher price inflation means creditors will demand for higher interest rates to compensate not only for assuming credit risks but also to cover for purchasing power losses from price inflation.

Should the credit transactions fail to consummate due to the dearth of agreement on interest rates between parties, the prospects of higher inflation would mean that savers will opt to spend their money, seek safehaven through hard assets or search for alternative assets or currency overseas which embodies capital flight.

The updated quarterly newsletter from Japan’s Ministry of Finance shows of the huge schedule of JGBs due for rollover this year ¥114.18 trillion and ¥79.04 trillion in 2014 (top window)[19].

The biggest owners of JGBs are the Japan’s financial sector particularly the banking system 42.7% life and Nonlife insurance 19.2% Public and private pension funds 7.1% and 3%, respectively. The financial sector accounts for 72% of the JGBs.

So considering the BoJ’s expressed inflation target of 2% these institutions will become natural sellers of bonds.

Banks have indeed become sellers, according to the Bloomberg[20]:

Japanese banks, which had been using their excess deposits to buy government bonds, have reduced their holdings as the central bank increases purchases. Lenders had 164 trillion yen of the securities in February, down from a record 171 trillion yen in March last year.

A sustained turmoil in the bond markets will jeopardize the refinancing of these maturing bonds, substantially raise the costs, may prompt for the accelerated selling by these institutions and increase the imminence of the risks of a default.

The same article notes that the Japanese authorities have been circumspect of risks posed by surging yields, from the same article:

Japan’s debt-servicing costs will rise 100 billion yen for each 10 basis-point increase in yields, Finance Minister Taro Aso said May 16

In a 2012 paper the IMF adds that higher rates will undermine capital from Japan’s banking and financial system[21]

Interest rate risk sensitivity is especially prevalent in regional banks and insurance companies (JGBs representing about 70 percent of life insurers' securities holdings and 90 percent of insurance cooperatives’ securities holdings). In addition, the main public pension scheme, as well as Japan Post and Norinchukin bank, also have large JGB exposures…

According to BOJ estimates, a 100 basis point (parallel) rise in market yields would lead to mark-to-market (MTM) losses of 20 percent of Tier-1 capital for regional banks (not taking into account net unrealized gains on securities), against 10 percent for the major banks.

Soaring interest rates will also weigh heavily on interest payments. Former controversial Morgan Stanley analyst, Andy Xie, now an independent economist, expects that at 2% interest rates, “the interest expense would surpass the total expected tax revenue (this year) of 42.3 trillion yen.[22]" Hedge fund manager Kyle Bass also sings almost the same tune noting that at 2% interest rate interest expense would comprise 80% of tax revenues[23].

In short, PM Abe and BoJ’s Kuroda have been now caught between the proverbial devil of supporting financial markets and the deep blue sea-the possible overshooting inflation target.

This also shows how authorities, despite the knowledge of risks, prefer short term solutions that come with a greater cost in the long run. Abenomics represents a political gambit whose consequence the Japanese citizens will have to bear.

Even before the last week’s turbulence, the BoJ’s bond buying according to the Wall Street Journal “will be equal in size to 70% of all new JGB issuance each month”[24]. Wow.

And given the burgeoning fiscal deficits[25] by the Japanese government which hedge fund manager Kyle Bass estimates at around ¥50 trillion a year[26], the BoJ’s programme of ¥60 trillion to ¥ 70 trillion ($683 billion) a year in asset purchases[27] will leave little room (¥10-20 trillion) for the BoJ to wiggle to institute financial stability measures.

The riot in Thursday’s bond markets prompted the BoJ to inject ¥2 trillion ($19.4 billion) which according to an article from the Bloomberg[28] signifies as the “second such market-calming infusion this month”. In other words, at the current rate and scale of stabilization measures, it will take only 5-10 “market-calming” sessions to wipe out the contingent ¥10-20 trillion fund.

This only means that the BoJ would need to substantially expand the current program in order to buy time.

But the Abenomics trend seems terminal and or irreversible.

The BoJ would need to expand more asset purchases in order to stabilize the market. On the other hand, expanding BoJ’s balance sheets would feed into the public’s inflation expectations. So this becomes an accelerating feedback mechanism that may lead to an eventual hyperinflation, if BoJ officials persist with such policies, or if they stop, a debt default.

We seem to be witnessing the culmination of one of the boldest experiment in modern day monetary system.

Abenomics has only been digging the Japanese economy swiftly deeper into the hole.

Will Japan’s Turmoil Signal the End of Easy Money Days?

The twin crash in Japan’s financial markets may be more than meets the eye.

The current financial markets boom has been prompting interest rates to climb higher for many nations.

10 year yields have begun to creep higher for crisis affected Eurozone sovereign papers (top window: Greece GGGB10-red orange, Portugal GSPT10Yr-green, Spain GSPG10YR orange and Italy GBTGR10-red). These nations has recently benefited from the Risk ON environment, prompted for by “do whatever it takes” policies and guarantees from the ECB as well as bank-pension funds related politically directed buying on such bonds.

And they seem to follow the footsteps of the developed market peers (lower window: Japan GJGB10-red orange, US USGG10YR-Green, Germany GDBR10 orange, and France GFRN10 red) whose interest rates have been moving higher earlier than the crisis stricken contemporaries.

But again interest rates affect each nation differently. Given the extremely high level of Japan’s debt, which makes them extremely interest rate sensitive, marginal increases has already jolted their markets

So far the twin crash has hardly put a squeeze on Japan’s Credit Default Swaps[29].

But again, the succeeding days will be very crucial. The coming sessions will establish whether the BoJ’s stabilization measures will delay the day of reckoning.

If not we should expect the mayhem in Japan’s bond markets to ripple across the world, which perhaps could be magnified by the derivatives markets.

Global OTC derivatives as of December 2012 totaled $633 trillion slightly lower than $ 639 trillion in June of the same year.

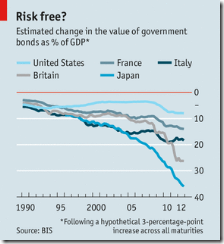

Interest rate derivatives account for $490 trillion or 77.4% of the overall derivative markets according to the Bank of International Settlements[30] (BIS). The bulk of which has been into interest rate swaps ($370 trillion) or about 75.5% of the interest rate derivative markets the rest have been forward rate agreements (FRA) and options. Yen denominated interest rate derivatives account for $ 54.812 trillion or 11.2% of the interest rate contracts.

The immense exposure by the derivative markets on interest rates extrapolates to heightened uncertainty as Japan’s bond markets draw fire.

While the direction of positions from such derivatives have not been disclosed, what should be understood is that a disorderly return of the bond market vigilantes would imply heightened counterparty risks that is likely to impact principally the financial and banking sector and diffuse into leverage sectors connected to them.

And given the extent of massive debt buildup around the world in the chase for yields, a Japan debt or currency crisis could easily be transmitted to highly leveraged economies. The result would be cascading implosion of bubbles.

There will hardly be any regional rescues as most nations will be hobbled by their respective busts.

However, central bankers of most nations will likely do a Ben Bernanke and this might change the scenario we have seen through or became accustomed to during the last decade.

Bottom line: Japan’s twin market crash for me serves as warning signal to the epoch of easy money.

Yet it is not clear if the actions of the BoJ will succeed in tempering down the smoldering bond markets, whom has been responding to policies designed to combust inflation.

If in the coming days the BoJ’s manages to calm the markets, then the good times will roll until the next convulsion resurfaces.

The BoJ will likely exhaust its program far earlier than expected and has to further expand soon to keep the party going.

However, if the bond vigilantes continue to reassert their presence and spread, then this should put increasing pressure on risk assets around the world.

Essentially, the risk environment looks to be worsening. If interest rates continue with their uptrend then global bubbles may soon reach their maximum point of elasticity.

We are navigating in treacherous waters.

In early April precious metals and commodities felt the heat. Last week that role has been assumed by Japan’s financial markets. Which asset class or whose markets will be next?

Trade with utmost caution.