The capital markets are desperate for continued hallucination. Central banks supply hallucinations. They create money, and the investing world pretends that this is capital. It isn’t capital. It is no more capital than heroin is a nutrient. Heroin is a tool for keeping people from coming to grips with reality. So is central bank monetary inflation. –Gary North

Mainstream Talking Points: The Irrelevance of Easy Money

Thursday’s Inquirer article opened with how the domestic financial markets had been shaken from a supposed turnaround in US monetary policies: “US Federal Reserve signaled that the regime of easy money—which has inflated asset valuations in emerging markets—would end by next year”[1].

Ironically the entire article went on to refute, or more appropriately, defend the status quo by sidestepping the issue of how “easy money” led to “inflated asset valuations”. The stereotyped politically tinged article cites the opinions of “economic managers” whose arguments banked on supposed “fundamentals”.

Such assurances comically emanate from talking heads who never saw this financial market rout coming in the first place.

The populist dogma feted by mainstream media to the public has been to project a “new order” for the Philippine markets and the economy whose direction has been etched on the stone as “up up and away!”.

Yet for the mainstream “experts” and the populist talking heads, recent events has been deemed as an anomaly, a temporal quirk, unreal or a just a metaphorical nightmare—which will go away soon.

Since such events don’t fit into their understanding of the world, which for them reality or “fundamentals” constitute as statistical aggregates, the natural reaction has been to deny them.

The bubble mentality has been so pronounced to the point that some experts even justify high valuations[2] of Philippines assets relative to other Asian peers due to “strong growth trajectory” and “long term growth prospects”. This time is different.

Such denials basically ignore the fact that market actions account for as “fundamentals”, they have been portentous of a dramatic change of economic-financial and even political environment.

Would sellers stampede out of or crash the markets without any motivations guiding their actions? Such would represent naïve presumptiveness.

Perhaps humongous political rallies in Brazil[3], Indonesia[4], and Turkey[5] could be writings on the wall.

If the transition from easy money to tight money will be sustained, then all of the inflated statistics from which current “fundamentals” (yes history) have been founded on, hence the “inflated asset valuations”, will dramatically get reconfigured.

Moreover, the obsession over accounting identities as impeccable measures of economic growth will be blown to smithereens or exposed for as duplicitous aggregates tainted by patent imperfections.

Heuristics camouflaged by economic terminologies and statistics hardly constitutes as economic analysis.

Popular delusions of “this time is different” brought about by credit expansion will face harsh reality soon.

Signs of Bursting Bond Bubble?

The mainstream cannot seem to fathom that monetary policies are hardly neutral and has relative impacts on each sectors of the economy.

They hardly understand or appreciate the causal relationship between monetary conditions with respect to asset markets, statistical economy and the real economy.

My guidepost from the start of the year[6]:

Let me repeat: the direction of the Phisix and the Peso will ultimately be determined by the direction of domestic interest rates which will likewise reflect on global trends.

And interest rates have indeed shaped the market’s direction.

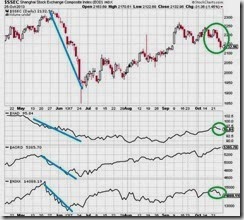

CLIMBING yields of the US 10 year treasury, which serves as important benchmarks for many credit markets, has accelerated or has intensified from its interim nadir last May.

Once the yields broke beyond the March highs of 2.05%, global markets began to seize up as shown by the recent decline of the S&P, and the nosedive in the Phsix (PCOMP) and ex-US global equity benchmark (MSCI World).

Last Friday, UST’s 10 year yields spiked to August 2011 levels[7].

The upheaval in US bond markets[8] has been broad based.

The biggest impact can mostly be seen in UST 5-10 year notes and the 30 year bonds as well as the Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPs) [lower pane].

Rising yields of TIPs suggest that the market’s expectation of inflation risks have, so far, been subdued.

Add to this recent surge of credit default swap premiums[9] both in the sovereign and corporate sector which underlies growing concerns over creditworthiness, it would seem a mistake to construe rising yields as a function of “economic growth”.

Instead the unraveling events seem as growing indications of concerns over credit quality conditions.

Bluntly put, we could be witnessing incipient signs of the bursting of global financial asset bubbles, spearheaded by the bond markets.

Fed Communique: To Taper or To Ease?

I would like to reemphasize too that the Ben Bernanke’s “Taper talk” really has substantially been a tactical communications signaling maneuver to maintain or preserve the central bank’s “credibility” by realigning policy stance with actions in the bond markets.

The incumbent FED’s easing policies which has been designed to “maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative”[10] has been confronted by the opposite or the unintended effects: rising long term interest rates.

10 year yields have been rising since July 2012. The FED implemented the QEternity 3.0 in September of 2012 which put downward pressure on rates for a mere THREE (3) month period. Yields then reversed course and crept higher until Japan’s PM Shinzo Abe’s nomination of Haruhiko Kuroda as Bank of Japan’s Chief. The appointment of Mr. Kuroda, who was widely expected to conduct aggressive monetary actions, practically served as the “sell on news” part of the “buy the rumor, sell the news” on Mr. Kuroda’s assumption to office. The announcement of Kuroda’s “arrow” of Abenomics plus the ECB’s interest rate cut last May has basically been negated by the ascendant yields.

In short, yields have been rising even before the Taper Talk.

This shows that it would not be accurate to say that Taper Talk caused higher yields. Instead, the Taper Talk essentially functioned as the “trigger” or the “outlet valve” for what has been a simmering pressure buildup for higher yields. The Taper Talk has really been an aggravating factor.

A further reality is that the “Taper Talk” mantra represents as selective focusing of the markets. The markets fixated on one aspect of the FOMC announcement while disregarding the rest.

The Fed’s official communique mentioned “taper” as an option “The Committee is prepared to increase or reduce the pace of its purchases” that is subject to arbitrary parameters set by them “will continue to take appropriate account of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases as well as the extent of progress toward its economic objectives”.

Taper has not been a foreordained path. To the contrary the increase in the pace of purchases has also been considered or discussed.

This has been reinforced by Mr. Bernanke’s press conference speech[11]:

The Taper Option: (bold mine)

If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year; and if the subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear. In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7 percent, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains, a substantial improvement from the 8.1 percent unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this program

The Easing Option:

I would like to emphasize once more the point that our policy is in no way predetermined and will depend on the incoming data and the evolution of the outlook, as well as on the cumulative progress toward our objectives. If conditions improve faster than expected, the pace of asset purchases could be reduced somewhat more quickly. If the outlook becomes less favorable, on the other hand, or if financial conditions are judged to be inconsistent with further progress in the labor markets, reductions in the pace of purchases could be delayed; indeed, should it be needed, the Committee would be prepared to employ all of its tools, including an increase in the pace of purchases for a time, to promote a return to maximum employment in a context of price stability

To repeat: The “taper” is an option, and not a definitive action, that the FED may or may not resort to. As much as taper is an option, so has “easing”.

Bond vigilantes itching for a grand entrance found the Taper speech as opportunity to flaunt their newfound power.

Asked about the “very sharp rise in real interest rates” over the last few weeks, the clueless Bernanke responds

Well, we were a little puzzled by that. It was bigger than it could be explained I think by changes the ultimate stock of asset purchases within reasonable ranges. So I think we have to conclude that there are other factors at work as well including again, some optimism about the economy, maybe some uncertainty arising. So, I'm agreeing with you that seems larger than it can be explained by a changing view of monetary policy. It's difficult to judge whether the markets are in sync or not

Rising yields over the past 11 months depicts of the diminishing marginal returns of such policies. This means that accumulation of current imbalances has essentially offset the wealth generating capacity of the economy or has severely damaged the process of real wealth generation that has led to a shrinkage in real savings.

As Austrian economist Dr. Frank Shostak explains[12]:

Contrary to popular thinking, an increase in the monetary flow is in fact detrimental to economic growth since it sets in motion an exchange of something for nothing — it leads to the diversion of real wealth from wealth generators to wealth consumers. This in the process reduces the amount of wealth at the disposal of wealth generators thereby diminishing their ability to enhance and maintain the infrastructure. This in turn undermines the ability to grow the economy.

Rising yields will either force the FED to align their policies with the bond markets or attempt to douse such conflagration with bigger inflationist policies.

Poker Bluff Redux

The US government and the banking system have become increasingly dependent on Fed’s actions.

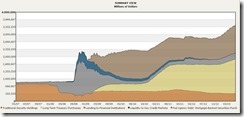

The balance sheet of the US Federal Reserve[13] has been stuffed with US Treasuries and mortgage backed securities (MBS)

The Fed possesses about 30.32% of all outstanding ten year an equivalent according to the Zero Hedge[14]. At the rate of purchases, the FED’s share of outstanding ten year will balloon to 90% in 2017, where the Zero hedge notes that “By the end of 2018 there would be no privately held US treasury paper”. And if fiscal deficits do shrink, a complete nationalization of bond markets will be sooner rather than in 2017-2018.

The same almost holds true for mortgages. As Euro Pacific Capital’s Peter Schiff recently pointed out[15], (bold mine)

While it's true that the Fed only owns 14% of all outstanding MBS (the "small fraction" he referred to in the press conference), it is by far the largest purchaser of newly issued mortgage debt. What would happen to the market if the Fed were no longer buying? There are no longer enough private buyers to soak up the issuance. Those who do remain would certainly expect higher yields if the option of selling to the Fed was no longer on the table. Put bluntly, the Fed is the market right now and has been for years.

Given the entrenched dependency relationship by the mortgage markets and by the US government on the US Federal Reserve, the Fed’s QE program can be interpreted as a quasi-fiscal policy whose major beneficiaries have been the political class and the banking class. Thus, there will be little incentives for FED officials to downsize the FED’s actions, unless forced upon by the markets. Since politicians are key beneficiaries from such programs, Fed officials will be subject to political pressures.

This is why I think the “taper talk” represents just one of the FED’s serial poker bluffs.

Besides, any withdrawal or a scaling back of QE will only stir up disorder, not only in the bond markets, but across the financial asset spectrum from which the current market bedlam serves as a useful template.

And in contrast to the popular idea that the FED will taper, again I think that surging interest rates and the attendant intensifying financial market turmoil eventually will impact on the FED’s dual mandate of “maximum employment and price stability”.

While the objective of “price stability”[16] has been focused on price inflation, the ongoing riots in the bond markets are equally signs of spreading instability that will interfere “with the efficient operation of the economy and can reduce economic growth”.

The FED obviously has been looking at the wrong places.

Such reemergent instabilities will compel the FED to expand their balance sheets. And I expect other central bankers to follow suit.

It is important to note too that with the stimulative effects of about $10 trillion[17] of global central bank asset expansion obviously fading, central bankers whom has recently been hailed as “superheroes”[18] for what has been perceived by media as having attained the elixir of policymaking will likely renew their attempt to reflate the markets and economies.

Aside from the political agenda, the previous round of so-called “successes” will provide the motivation for FED and other central bankers to adapt the same “path dependent[19]” recourse.

As I have been repeatedly saying, central bankers will likely push inflationism to the limits: QE 1.0, QE 2.0, QEternity, Abenomics and etc…

And with the diminishing access to what government labels as “risk free” bonds or “safe assets”, which will affect bank capital adequacy regulations and bank risk profiles, central bankers are likely to expand purchases to include other financial assets, perhaps equities, corporate bonds and others.

But there will likely be more pain ahead before the next round of central bank actions.

“Deflation” has been conventionally used as the convenient bogeyman from which central banks justify their actions. The ongoing meltdown in US Treasuries, credit markets, emerging market assets, US muni bonds, MBS, commodities and increased selling pressure on developed market stocks signifies as the convenient backdrop for the next round of rescue measures.

But if the wealth generators in the real economy has been severely damaged, and if the unfolding rout in financial asset markets will be deep enough to traumatize participants, the next wave of reflationary policies will likely spur a spike in price inflation, rather than a resumption of the speculative excess or the risk ON environment.

We may be in the next phase of the inflation cycle.

As the great dean of Austrian school of economics, Murray N. Rothbard explained[20] (bold mine)

The ultimate result of a policy of persistent inflation is runaway inflation and the total collapse of the currency. As Mises analyzed the course of runaway inflation (both before and after the first example of such a collapse in an industrialized country, in post-World War I Germany), such inflation generally proceeds as follows: At first the government's increase of the money supply and the subsequent rise in prices are regarded by the public as temporary. Since, as was true in Germany during World War I, the onset of inflation is often occasioned by the extraordinary expenses of a war, the public assumes that after the war conditions including prices will return to the preinflation norm. Hence the public's demand for cash balances rises as it awaits the anticipated lowering of prices. As a result, prices rise less than proportionately and often substantially less than the money supply, and the monetary authorities become bolder. As in the case of the Assignats during the French Revolution, here is a magical panacea for the difficulties of government: pump more money into the economy, and prices will rise only a little! Encouraged by the seeming success, the authorities apply more of what has worked so well, and the monetary inflation proceeds apace. In time, however, the public's expectations and views of the economic present and future undergo a vitally important change. They begin to see that there will be no return to the prewar norm, that the new norm is a continuing price inflation — that prices will continue to go up rather than down. Phase two of the inflationary process ensues, with a continuing fall in the demand for cash balances based on this analysis: "I'd better spend my money on X, Y, and Z now, because I know full well that next year prices will be higher." Prices begin to rise more than the increase in the supply of money. The critical turning point has arrived.

This implies that next set of central bank actions will likely undergird a transitional period from bursting bubbles to stagflation. Once stagflation becomes the order of the day the next risks will be one of runaway inflation.

Ultimately it will be the feedback loop between the actions of policymakers and markets responses to them that will shape the direction of markets.

So far, as noted above, rising interest rates appear as signs of bursting bubbles across the globe.

And global bond markets serve as our guideposts as I previously wrote[21]

What I am saying is that unless the upheavals in global bond markets stabilize, there is a huge risk of market shock that may push risk assets into bear markets.

Has the Bond Vigilantes landed on ASEAN Bond Markets?

As of the previous week, the upheaval in emerging market bonds has barely landed on the ASEAN shores, except Indonesia.

But two weeks back I warned, “the vastly narrowed Philippine-US spread may or could be an accident waiting to happen via reversion to the mean”[22]

Remember, the yield of the 10 year Philippine bonds seem to suggest that her credit risk profile has been nearly at par with Malaysia and has (astoundingly) surpassed Thailand, which for me, signifies as a bubble.

And as I have earlier pointed out, the interest rate spread between the US and Philippines has substantially narrowed. This reduces the arbitrage opportunities and thus providing incentives for foreign money to depart from local shores to look for opportunities elsewhere or perhaps take on a “home bias” position.

The EM and ASEAN bond markets are highly vulnerable to market shocks as recent events have shown.

Just looking at the IMF calculated Nominal GDP per capita[24], notably there has been a gulf in data between the Philippines US$ 2,617 on one hand, and Indonesia $3,910, Thailand $5,678 and Malaysia $10,304 on the other hand. Ironically, current bond yields which reflects on credit risks, suggests that the Philippines shares the same profile with her much ‘wealthier’ peers.

Even if the popular assumption that the Philippines will outperform her contemporaries in terms of growth over the coming years holds true (which isn’t), seen from the perspective in nominal per capita GDP, such whale of the difference indicates that Philippine bond yields seem as having been blatantly mispriced.

This may have been mainly due to recent credit rating upgrades (which will be put to test), and the rest from the credit bloated statistical growth based on easy money policy regime which is about to change.

Regardless of what BSP officials will say on sustaining low interest environment, if the selloff in global bonds persists, this will show up in Philippine bond yields.

10 year bond Philippine bonds yields[25] moved significantly higher during the Thursday and Friday’s stock market rout.

Last week’s bond market actions seem as the second attempt to break beyond the 4% level. I believe that once a breakout has been attained, the upward movements will intensify.

Our neighbors have already began to show signs of distress in their bond markets…

Thailand and Malaysia seems to have joined Indonesia in a trajectory of ascendant yields

I don’t share the view that will entirely be a story of current accounts and external debt as some experts suggest.

Malaysia still has current account surplus but a rapidly shrinking one. Also Malaysia’s external debt has been trending lower since 2008. Yet yields of Malaysia’s 10 year bonds[26] have broken away from the highs of 2013.

Thailand recently posted a current account deficit. Thailand’s current account has been seesawing between surpluses and deficits. Thailand’s external debt has leapt by 60% since 2010. But like the Philippines, yields of Thailand’s 10 year bonds[27] appear to be making a second attempt to breach the 4% level.

So based on relative external conditions Indonesia has borne the initial brunt of a bond market[28] selloff. But the pressures on the ASEAN bond market appear to be spreading. Indonesia recently raised interest rates, but likewise announced her version of QE.

At the end of the day, sustained tightening of money conditions will not only expose on external fragilities but likewise internal imbalances or domestic bubbles. The recognition of the unsustainability of domestic assets bubbles may further incentivize liquidations already triggered by continuing collapse of the global bond markets.

So far actions in the bond markets has had variable effects on equities. The above shows of the variable stock market losses since the close of the week in May 31st.

This may be due to many factors such as capital regulations, degree of foreign ownership and etc…

Finally while ASEAN financial assets reveals of mixed degrees of selling pressure, what has converged so far has been a sharp selloff in domestic currencies.

Yet part of the currency selloffs has been cushioned by central bank actions. For instance last week, the BSP was reported to have stepped in via open market operations to “stem the decline and smooth out the volatility”[29]

It would be interesting to see how all these selling will affect the region’s vaunted Gross International Reserves.

Will there be enough reserves to shield a sustained stream of outflows? Or will domestic central banks sharply raise rates?

Global Bond Markets Determines the Fate Of Asset Markets

Bottom line: Markets will remain highly volatile, however as previously noted, volatility will go on both direction but with a downside bias, unless again, global bond markets are pacified.

Unsettled global bond markets will continue to hound financial markets.

Emerging market outflows reached $19 billion during the past three weeks the most since 2011. This may be part of the “reversal of the $3.9 trillion of cash that flowed into emerging markets the past four years” according to a report from Bloomberg[30].

Such claim will ultimately depend on the conditions of the bond markets.

Crashing markets means that losses will continue to mount and begin to affect balance sheets of major institutions around the world.

For instance, China’s PBoC reversed course from attempting to ferret out shadow banks and reportedly infused money to a financial institution[31] as rumors floated that one of the largest commercial bank in China, the Bank of China defaulted. The latter denied such allegations[32].

Eventually smoke will likely become fire.

On the other hand, a flurry of selling has prompted one of the market’s largest exchange-traded fund sponsors of municipal bond ETFs in the US to suspend share redemptions[33].

These are initial symptoms.

Eventually too the suppression of losses will become public which increases the likelihood of contagions.

And as stated before, the reverse reflexive feedback loop from liquidations and realized losses will affect expectations and subsequently prospective actions and vice versa.

And given the multiple hotspots brought about by the unravelling global bond markets, it would not be prudent for anyone to expect an immediate resolution on these.

Even if the US Federal Reserve decides to intervene, it would take coordinated or collaborative actions by major central banks to possibly soothe the bond markets.

But again such band-aid treatment will likely have a short term effects considering that real savings may have been substantially drained and that real wealth generators of the economy have been damaged by such policies.

Highly indebted governments will also be put on spotlight. This puts to the fore the increased risks of a debt crisis from a major economy that may ripple across the world and worsen current conditions.

But media will be stuffed with rabid denials.

If you happen to read or hear of talking heads who claim that the current selloff represents a bottom, check out first if they saw this market carnage coming. Also find out if they have “skin in the game”, before believing them.

As my favorite iconoclast Nassim Taleb recently wrote[34]

predictions in socioeconomic domains do not work, but predictors are rarely harmed by their forecasts. Yet we know that people take more risks after they see a numerical prediction. The solution is to ask – and only take into account – what the predictor has done, or will do in the future.

It’s your money that is at risk, not theirs.

So do yourself a favor of doing independent research.

Trade with utmost caution.