The choice of the good to be employed as a medium of exchange and as money is never indifferent. It determines the course of the cash-induced changes in purchasing power. The question is only who should make the choice: the people buying and selling on the market, or the government? It was the market that, in a selective process going on for ages, finally assigned to the precious metals gold and silver the character of money. For two hundred years the governments have interfered with the market’s choice of the money medium. Even the most bigoted étatists do not venture to assert that this interference has proved beneficial—Ludwig von Mises

In this issue

PSE Divergence Confirmed —

The September Breakout That Redefined Philippine Mining in the Age of Fiat

Disorder

I. April 2023: The Thesis

That Time Has Now Validated

II. September’s Seismic

Shift: Mining Index Outpaces the PSEi

III. The Fiat Fracture:

Gold's Three-Legged Bull Market and the Chronicle of Monetary Rupture

IV. Gold as Signal of

Systemic Stress

V. Fracture Points: Tumultuous

Geopolitics and the New War Economy

VI. A Militarized Global

Economy and The Fiscal–Military Feedback Loop

VII. Economic Warfare:

Tariffs, Fragmentation, and Supply Chain Bifurcation

VIII. World Central Banks

Signal Distrust: The Gold Accumulation Surge and Fiat Erosion

IX. The Paradox of

Philippine Mining Reform: Bureaucratic Control over Market Forces

X. The Philippine Mining

Index Breakout: Gold Leads, Nickel Surprises, Copper Lags and the Speculative

Spillover

XI. Conclusion: The Uneasy Return of Hard Assets in a Soft-Money World

PSE Divergence Confirmed — The September Breakout That Redefined Philippine Mining in the Age of Fiat Disorder

Beyond the PSEi: Tracking the Philippine Mining Index's decoupling, the gold-fiat fracture, and the systemic risks that power resource equities.

I. April 2023: The

Thesis That Time Has Now Validated

Figure 1

Back in April 2023, we predicted that rising gold prices would boost the Philippine mining index for several reasons: (see reference)

1. Unpopular – It is the most unpopular and possibly the "least owned" sector—even "the institutional punters have likely ignored the industry." As proof, it had the "smallest share of the monthly trading volume since 2013."

2. Lack of Correlation – "its lack of correlation with the PSEi 30 should make it a worthy diversifier"

3. Potential Divergence – We wrote that "the current climate of overindebtedness and rising rates seen with most mainstream issues, the market may likely have second thoughts about this disfavored sector. Soon."

4. Formative Bubble – We posed that "If the advent of the era of fragmentation or the age of inflation materializes, could the consensus eventually be chasing a new bubble?"

Well, media coverage hardly noticed it, but the relative performance of the Mining sector vis-à-vis the PSEi 30—or the Mining/PSEi ratio—made significant headway last September. It critically untethered from its 5-year consolidation phase. (Figure 1, topmost chart)

Recall: mines suffered a brutal 9-year bear market from 2012 to 2020. The Mining/PSEi ratio hit its secular low during the pandemic recession, pirouetted to the upside, peaked in September 2022, but remained rangebound—nickel lagged, and gold lacked sufficient momentum to lift the index.

II. September’s Seismic Shift: Mining Index Outpaces the PSEi

That dramatically changed in September. The Mining/PSEi ratio experienced a seismic breakout, powered by a decisive thrust in gold mines, buoyed further by surging nickel mines.

But this time may be different. The 2002–2012 bull cycle was driven by Mines outrunning a similarly bristling PSEi 30. Today, the Mines are diverging—operating antithetically from the broader index—a potential reflection of gradual and reticent transition of market leadership. (Figure 1, middle graph)

The September numbers underscore the shift (Figure 1, lowest table)

PSEi 30: –3.28% MoM, –18.14% YoY, –6.46% QoQ, –8.81%

YTD

Mining Index: +25.86% MoM, +47.97% YoY, +35.07% QoQ, +63.96% YTD

So yes, it fulfilled our projections of a bull

market in motion while validating our ‘diversifier’ thesis. Still, despite its

massive run, the sector remains disfavored—its share of the monthly main board

volume remains the smallest.

Figure 2

Even with the gaming sector’s bubble showing cracks, speculative interest in PLUS and BLOOM (at 4.38%) nearly matched the ten-issue Mining Index (4.46%) in September. In short, market sentiment still favors gaming over mining. (Figure 2, topmost image)

Ultimately, the mining sector’s performance—and its transition to a potential secular bull market—will hinge on its underlying commodities.

In 2016, we wrote,

Divergence or rotation can only be affirmed when gold mining stocks will move independently from the mainstream stocks. The best evidence will emerge when both will move in opposite directions. This had been the case from 2012 through 2015 when miners collapsed while the bubble industries blossomed. It should be a curiosity to see when both trade places. Time will tell. [italics original] (Prudent Investor, 2016)

That’s a bullseye!

III. The Fiat Fracture: Gold's Three-Legged Bull Market and the Chronicle of Monetary Rupture

Gold’s long-term ascent is a chronicle of monetary rupture. (Figure 2, middle chart)

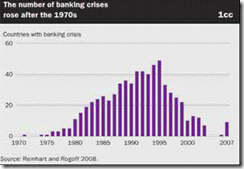

The first major break came under Franklin D. Roosevelt, with Executive Order 6102 (1933) and the Gold Reserve Act (1934), which outlawed private gold ownership and revalued the dollar’s gold peg from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. This statutory debasement set the modern precedent for political interference in money.

The second rupture—Nixon’s 1971 “shock” ending Bretton Woods convertibility—ushered in the fiat era. Untethered from monetary discipline, gold surged from $35 to ~$670 by September 1980, a 19x return over nine years, driven by double-digit inflation, oil shocks, and institutional distrust. This marked the first leg of the post-gold-standard bull cycle under the U.S. dollar’s fiat regime.

The second leg (2001–2012) unfolded over eleven years, beginning around $265 in February 2001 and peaking near $1,738 in January 2012—a 6.6x return.

This phase reflected a response to cascading financial crises and aggressive monetary easing: the dotcom bust, 9/11, the Global Financial Crisis, and the Eurozone debt spiral. Central bank interventions—QE and ZIRP from the Fed and ECB—amplified gold’s role as a hedge against fiat dilution.

The third leg (2015–) began in late 2015, bottoming near $1,050 in the aftermath of China’s devaluation. Over the next decade thru today, gold climbed past $3,800—a ~3.6x return—driven by global central bank accumulation, geopolitical fracture, asset bubbles, inflation spillovers, and record leverage across public and private sectors.

As a sanctuary asset, gold has not only preserved purchasing power but also signaled systemic fragility. Real (inflation-adjusted) prices have reached all-time highs, underscoring gold’s function as a monetary barometer. (Figure 2, lowest diagram)

Today, its strength reflects more than cyclical momentum—it mirrors the widening cracks of the fiat era.

Gold’s trajectory—marked by 9-, 11-, and 10-year legs—suggests that mining valuations may be more tightly coupled to global monetary dysfunction than domestic policy alone.

With gold now approaching USD 4,000, history suggests we may well see prices reach at least USD 6,000.

For resource-driven economies like the Philippines, this episodic repricing offers a potent lens for evaluating mining equities. Rising gold valuations, persistent inflation, and the flight to real assets amid waning faith in fiat systems suggest that mining performance may be more tightly coupled to global monetary dysfunction than domestic policy alone.

Still, each leg has emerged from distinct fundamentals—past performance may rhyme, but not reprise.

IV. Gold as Signal of Systemic Stress

Last March, we launched a three-part series forecasting that gold would sustain its record-breaking run.

In the first installment, we argued that gold has

historically served as a leading indicator of economic and financial stress:

"gold’s record-breaking runs have consistently foreshadowed major

recessions, economic crises, and geopolitical upheavals."

Figure 3

Today, that reflexive relationship remains in play.

As global growth falters under the weight of fiscal imbalance and geopolitical strain, central banks have turned decisively toward rate cuts, reversing the tightening cycle that began in 2022. By September, the scale of collective policy easing has already approached pandemic-era levels, underscoring a synchronized monetary response to mounting economic stress. (Figure 3, topmost window)

V. Fracture Points: Tumultuous Geopolitics and the New War Economy

In the second part, we explored how monetary disorder underpins gold’s sustained upside. "Gold’s record-breaking rise may signal mounting fissures in today’s fiat money system, " we wrote, “fissures expressed through escalating geopolitical and geoeconomic stress. "

Those fissures have widened. Over the past month, geopolitical tensions have intensified across multiple fronts, amplifying systemic risks for both commodity markets and global capital flows. In Europe, the Ukraine war has evolved from proxy engagement to near-direct confrontation, punctuated by Putin’s claim that "all NATO countries are fighting us."

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán echoed this unease, posting on X: (Figure 3, middle picture)

"Brussels has chosen a strategy of wearing Russia down through endless war… sacrificing Europe’s economy, and sending hundreds of thousands to die at the front. Hungary rejects this. Europe must negotiate for peace, not pursue endless war."

Paradoxically, Hungary is part of EU and NATO.

In the Middle East, Trump’s proposed Gaza peace plan has been welcomed by parts of the EU but criticized by both Israeli hardliners and Hamas, exposing deep political rifts that could derail any lasting truce.

Washington has also expanded its Caribbean military buildup apparently eyeing Venezuela—a Russian ally—under the pretext of targeting “drug smugglers.”

Compounding these tensions are the looming U.S. government shutdown, ICE-fueled riots, EU fragmentation, and territorial disputes across Asia (including the Thai-Cambodia and South China Sea flashpoints). Together, these developments erode international interdependence and deepen the sense of global instability.

VI. A Militarized Global Economy and The Fiscal–Military Feedback Loop

Adding fuel to the fire, debt-financed fiscal stimulus through military spending has reached unprecedented scale. According to SIPRI, global military expenditures rose 9.4% in real terms to $2.718 trillion in 2024—the highest total ever recorded and the tenth consecutive year of increase. (Figure 3, lowest visual)

This war economy buildup echoes historical patterns, where militarism became not just a tool of statecraft but a structural imperative.

Modern defense economies increasingly resemble historical warrior societies such as Bushido Japan, Sparta, and Napoleonic France, where militarism evolved from a tool of power into a systemic necessity.

In these societies, idle warriors or elite military classes threatened internal stability, compelling leaders to redirect aggression outward. Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea, for instance, was less about conquest than about pacifying a restless samurai class.

Today’s massive defense spending serves a parallel function: sustaining industrial output, protecting elite interests, and demanding perpetual geopolitical justification. The result is a fiscal–military feedback loop in which peace itself undermines the architecture of power.

This militarized economic order breeds a dangerous paradox: when growth depends on arms production and deterrence, the line between defense and aggression dissolves. As nations over-arm to preserve influence and momentum, the world risks sliding into a self-fulfilling conflict dynamic—where fiscal expansion, political ambition, and national pride coalesce into the very forces that once ignited global wars.

VII. Economic Warfare: Tariffs, Fragmentation, and Supply Chain Bifurcation

These geopolitical flashpoints are layered atop escalating geoeconomic risks that mirror economic warfare.

The U.S. has rolled out sweeping new tariffs—10% on lumber and 25% on furniture and cabinetry—adding to earlier steel and aluminum levies that have rattled European industries. With a stronger euro hurting export competitiveness and rising trade barriers disrupting supply chains, Europe’s manufacturing base faces mounting stress.

The U.S. recently raised tariffs on Philippine exports to 19%, part of a broader “reciprocal” trade posture that threatens ASEAN and EU economies alike. Export controls targeting Chinese tech and semiconductor firms underscore the growing bifurcation of global supply chains, especially in the AI and chip sectors.

VIII. World Central

Banks Signal Distrust: The Gold Accumulation Surge and Fiat Erosion

Figure 4

Amid this widening fragmentation, central banks have accelerated their gold accumulation—buying despite record-high prices.

As the World Gold Council reported, central banks added a net 15 tonnes of gold in August, consistent with the March–June monthly average, marking a rebound after July’s pause. Seven central banks reported increases of at least one tonne, while only two reduced holdings. (Figure 4, topmost and middle charts)

Notably, as political institutions, central bank reserve management decisions are not profit but politically driven.

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), additionally, was the world’s largest seller of gold reserves in 2024, citing profit-taking at higher prices. Yet in 2025, it resumed small purchases—ironically, at even higher price levels. (Figure 4, lowest graph)

Figure 5

Measured in Philippine pesos, gold and silver prices are extending their streak of record-breaking highs (Figure 5, upper window)

As history reminds us, the BSP’s massive gold sales in 2020 preceded the 2022 USD/PHP spike, suggesting that the 2024 divestment—intended to support the peso’s soft peg—could again foreshadow a breakout above PHP 59, perhaps by 2026?

Most strikingly, global central banks’ gold reserves have grown so rapidly that their aggregate gold holdings are now nearly on par with U.S. Treasury holdings—a clear sign of eroding faith in the contemporary U.S. dollar-based order. (Figure 5, lower image)

The modern-day Thucydides Trap—intensifying hegemonic competition expressed not only in geopolitics, but also in economic, financial, and monetary spheres—has increasingly powered the gold-silver tandem.

Viewed in this light, as gold rises against all currencies, the message is clear: it is not gold that’s appreciating, but fiat money that’s depreciating. Gold is no longer just insurance asset— it is, and remains, money itself.

IX. The Paradox of Philippine Mining Reform: Bureaucratic Control over Market Forces

In the absence of commodity spot and futures markets—a critical handicap to price discovery, risk management, and capital formation—the state’s default response has been to expand taxation and administrative controls instead of developing genuine market mechanisms.

Rather than pursuing market liberalization or introducing commodity exchanges to improve efficiency and productivity, the Philippine social democratic paradigm of reform remains fixated on taxation, administration, and bureaucratic control.

The passage of the Enhanced Fiscal Regime for Large-Scale Metallic Mining Act (RA 12253) and the push for the Mining Fiscal Reform Bill mark the government’s latest attempt to "modernize" the fiscal framework of the mining industry.

On paper, these reforms promise stronger oversight, greater transparency, and a "fairer share" of mineral wealth between the state and the private sector. The new regime introduces margin-based royalties, a windfall profits tax, and project-level accounting rules meant to simplify tax compliance and reduce leakages. Yet, beyond the reformist veneer lies a system still anchored on bureaucratic discretion—where regulators retain broad authority to interpret profitability thresholds, accounting standards, and tax computations.

In practice, this discretion perpetuates the opacity and arbitrariness that the law sought to correct. Rather than institutionalizing transparency, the framework risks entrenching regulatory capture, enabling bureaucrats to negotiate or manipulate fiscal obligations behind closed doors.

The very mechanisms intended to enhance oversight—royalty audits, windfall assessments, and transfer pricing reviews—may instead become new venues for rent-seeking and selective enforcement. This tension between statutory ambition and administrative reality leaves the industry vulnerable not only to corruption but also to uneven enforcement across operators and regions—cronyism.

In the short term, elevated metal prices could conceal these governance flaws, boosting fiscal receipts and lifting mining equities under the illusion of reform-led success. But when the commodity cycle turns, the cracks will widen: weak oversight, inconsistent standards, and arbitrary taxation could resurface as deterrents to investment and valuation stability.

Thus, what was framed as a fiscal modernization drive may ultimately reinforce the industry’s old paradox—where boom times mask systemic fragility, and reforms collapse when prices fall.

X. The Philippine Mining Index Breakout: Gold Leads, Nickel Surprises, Copper Lags and the Speculative Spillover

Lastly, while gold mining shares primarily contributed to the breakout of the Philippine Mining Index, nickel mines also sprang to life and added to the rally. The Philippine Stock Exchange recalibrated the composition of the Mining Index last August to reflect sectoral momentum.

Gold-copper Lepanto A and B replaced Benguet A and B,

while gold-silver miner Oceana Gold was newly included.

Figure 6

This partial reconstitution, combined with price action, reshaped the index’s internal weightings: as of October 3, gold-copper mines accounted for 74.65%, nickel 23.53%, and oil just 1.83%—a notable shift from March 31’s 68.3%-27.44%-4.25% distribution. (Figure 6 topmost graph)

From March 31st to October 3rd, gold mining shares surged 112%, driven by tailwinds from soaring gold and silver prices. Nickel mining shares, surprisingly, jumped 66.4% despite depressed global nickel prices. Meanwhile, solo oil exploration firm PXP Energy sank 16.5%.

The biggest ranked mines in the index, in descending order, were Apex Mining, OceanaGold, Philex, Nickel Asia, and Atlas Consolidated. (Figure 6, second to the top image)

USD prices of Silver and Copper surging while Nickel consolidates. (Figure 6 second to the lowest visual)

While gold’s rally was the primary engine of the index breakout—amplified by the inclusion of more gold-heavy names—the rebound in nickel miners was more ironic.

With easy money fueling an “everything bubble,” a rising tide appears to be lifting all mining boats.

Another factor is that local nickel miners have mirrored the moves of international ETFs such as the Sprott Nickel Miners ETF [Nasdaq: NIKL], which advanced largely on global liquidity flows rather than on improvements in the underlying metal market. (Figure 6, lowest diagram)

In essence, the surge in nickel shares reflects financial rotation and speculative spillover—capital chasing laggards and cyclical exposure amid abundant liquidity—rather than any meaningful recovery in nickel fundamentals. If the bids are to be believed, nickel prices would eventually have to rise and remain elevated; otherwise, the rally risks running ahead of earnings reality.

Meanwhile, despite a resurgent copper price—also mirrored in ETFs like the Sprott Copper Miners ETF [Nasdaq: COPP]—some local copper mines have made little progress in scaling higher.

We are yet to see substantial breakouts from the peripheral mines, suggesting that speculative flows have been highly selective, favoring liquidity and index-weighted names over broader participation.

Ironically, the divergence between copper and nickel prices underscores the fragility of the latter’s mining rally.

While copper’s surge has been confirmed by both spot prices and mining equities—reflected in the coherent ascent of ETFs like COPP—nickel’s stagnation contrasts sharply with the outsized gains in nickel mining shares and ETFs like NIKL.

This disconnect suggests mispricing: a speculative equity bid front-running a commodity rebound that hasn’t arrived. Without confirmation from the metal itself, the feedback loop sustaining nickel equities risks collapse, exposing the rally as a liquidity mirage rather than a durable trend.

XI. Conclusion: The Uneasy Return of Hard Assets in a Soft-Money World

The Philippine mining sector’s transformation from pariah to rising star is both cyclical and structural. It reflects not only higher commodity prices but also the global search for hard assets in an era of currency debasement, geopolitical fracture, and policy incoherence.

Gold’s rise tells a story of distrust in fiat money; nickel’s divergence, of speculative excess born of liquidity overflow.

The mining index’s ascent thus mirrors the world’s economic psychology—a blend of fear and greed, of safe-haven accumulation and ultra-loose money–financed speculative rotation.

Whether this is a sustainable repricing or a liquidity mirage will depend on whether global monetary and fiscal regimes stabilize—or fracture further. The former seems close to impossible; the latter, increasingly probable.

Either way, the Philippine mining story has become a proxy for something much larger: the uneasy return of hard assets in a soft-money world.

Postscript: No trend moves in a straight line. Gold, silver, and Philippine mining shares are now extensively overbought—inviting a countercyclical pause, not an end, to their ascent.

____

References

Ludwig von Mises, The Real Meaning of Inflation and Deflation, January 2, 2024, Mises.org

Prudent Investor Newsletter, Investing Gamechanger: Commodities and the Philippine Mining Index as Major Beneficiaries of the Shifting Geopolitical Winds! Substack, April 27, 2023

Prudent Investor Newsletter, Phisix 6,650: Resurgent Gold, Will Mining Sector Lead in 2016? Negative Yield Spread Hits 1 Month Bill-10 Year Treasuries!, Blogspot February 15, 2016

Prudent Investor Newsletter Do Gold’s Historic Highs Predict a Coming Crisis? Substack, March 30, 2025

Prudent Investor Newsletter, Gold’s Record Run: Signals of Crisis or a Potential Shift in the Monetary Order? (2nd of 3 Part Series), Substack, March 31, 2025

Prudent Investor Newsletter, How Surging Gold Prices Could Impact the Philippine Mining Industry (3rd of 3 Series), Substack, April 02, 2025

Prudent Investor Newsletter, The Long-Term Price Trend and Investment Perspective of Gold, Blogspot, August 02, 2020