Bloomberg columnist, author and Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) analyst Amity Shlaes warns about the complacency of political authorities over inflation. (hat tip Professor Antony Mueller)

“Sudden” is more like it. The thing about inflation is that it comes out of nowhere and hits you. Monetary policy is like sailing. You’re gliding along, passing the peninsula, and you come about. Nothing. Then the wind fills the sail so fast it knocks you into the sea. Right now, the U.S. is a sailboat that has just made open water, and has already come about. That wind is coming. The sailor just doesn’t know it.

“Sudden” has happened to us before. In World War I, an early version of what we would call the CPI-U, the consumer price index for urban areas, went from 1 percent for 1915 to 7 percent in 1916 to 17 percent in 1917. To returning vets, that felt awful sudden.

The popular mainstream ‘begging the question’ argument on consumer price inflation goes something like this: inflation risk is minimal, because there has been little signs of inflation today.

Present and past actions have been construed as extending to the future, with little regards to the cause-and-effect relationship from implemented policies such as money printing or zero bound rates. In reality, these arguments have been pushed to justify more inflationist-interventionist policies: No inflation? Have more inflation.

Yet like natural disasters, inflation wreaks havoc at the least expected moments.

The volatile episodes of US CPI inflation coincided with wars (World War I, World War II and the Vietnam War). (chart from tradingeconomics.com)

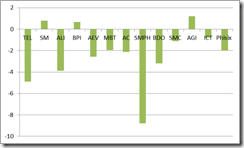

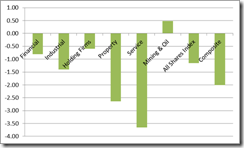

In a relative sense, today’s US CPI inflation environment has been ‘calmer’ than the current periods. Even if the US has been engaged in numerous imperialist wars, along with the huge welfare state that substantially contributes to the ballooning record fiscal or budget deficits. (chart from the Heritage Foundation)

chart from Cleveland Federal Reserve

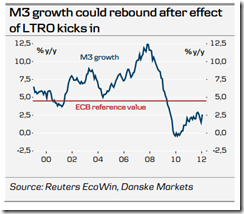

And this comes amidst the exploding balance sheet of the US Federal Reserve. The US Federal Reserve has topped China as the largest owner of US treasuries, which means that the US central bank has become the key source of financing for the US government.

And these banking based financing of public expenditures are inflationary. The great Murray N. Rothbard explained

Deficits mean that the federal government is spending more than it is taking in in taxes. Those deficits can be financed in two ways. If they are financed by selling Treasury bonds to the public, then the deficits are not inflationary. No new money is created; people and institutions simply draw down their bank deposits to pay for the bonds, and the Treasury spends that money. Money has simply been transferred from the public to the Treasury, and then the money is spent on other members of the public.

On the other hand, the deficit may be financed by selling bonds to the banking system. If that occurs, the banks create new money by creating new bank deposits and using them to buy the bonds. The new money, in the form of bank deposits, is then spent by the Treasury, and thereby enters permanently into the spending stream of the economy, raising prices and causing inflation. By a complex process, the Federal Reserve enables the banks to create the new money by generating bank reserves of one-tenth that amount. Thus, if banks are to buy $100 billion of new bonds to finance the deficit, the Fed buys approximately $10 billion of old Treasury bonds. This purchase increases bank reserves by $10 billion, allowing the banks to pyramid the creation of new bank deposits or money by ten times that amount. In short, the government and the banking system it controls in effect "print" new money to pay for the federal deficit.

Thus, deficits are inflationary to the extent that they are financed by the banking system; they are not inflationary to the extent they are underwritten by the public.

While we cannot exactly predict exactly when CPI inflation is bound to hit the US economy, given the recent actions by the US Federal Reserve and US Federal government, we understand though that inflation will eventually rear its ugly head.

The question is a WHEN rather than an If. And to what degree of inflation.

And worst, since the world has operated on a monetary standard based on the US dollar, the effects of US inflation will be worldwide.

The basis for such prediction is our theoretical understanding of the 3 stages of inflation

As the great Ludwig von Mises pointed out, (bold highlights mine)

In the early stages of an inflation only a few people discern what is going on, manage their business affairs in accordance with this insight, and deliberately aim at reaping inflation gains. The overwhelming majority are too dull to grasp a correct interpretation of the situation. They go on in the routine they acquired in non-inflationary periods. Filled with indignation, they attack those who are quicker to apprehend the real causes of the agitation of the market as "profiteers" and lay the blame for their own plight on them. This ignorance of the public is the indispensable basis of the inflationary policy. Inflation works as long as the housewife thinks: "I need a new frying pan badly. But prices are too high today; I shall wait until they drop again." It comes to an abrupt end when people discover that the inflation will continue, that it causes the rise in prices, and that therefore prices will skyrocket infinitely. The critical stage begins when the housewife thinks: "I don't need a new frying pan today; I may need one in a year or two. But I'll buy it today because it will be much more expensive later." Then the catastrophic end of the inflation is close. In its last stage the housewife thinks: "I don't need another table; I shall never need one. But it's wiser to buy a table than keep these scraps of paper that the government calls money, one minute longer."

A fundamental example has been the most recent bout of hyperinflation which buffeted Zimbabwe’s economy during the last decade, which I posted three years back.

When inflation strikes, it slams like a tidal wave. Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation produced a hockey stick like effect, similar to Weimar Germany’s experience.

While the risk of hyperinflation is not yet imminent, if the current path of inflationist policies is sustained, then this would enhance the probability of such a risk.