``All of us are ignorant of most of what there is to know." Professor Richard Dawkins, British Ethologist, Evolutionary Biologist, and popular science author

Anybody arguing that stock markets are strictly determined by traditional fundamental metrics should look at the current earnings environment of the US S&P 500 in figure 1.

Figure 1: chartoftheday.com: Annual S&P 500 Earnings Collapsed!

Figure 1: chartoftheday.com: Annual S&P 500 Earnings Collapsed!

As you would notice, the inflation adjusted earnings has essentially fallen off the cliff.

According to chartoftheday.com, the ``chart illustrates how earnings are expected (38% of S&P 500 companies have reported for Q2 2009) to have declined over 98% since peaking in Q3 2007, making this by far the largest decline on record (the data goes back to 1936). In fact, real earnings have dropped to a record low and if current estimates hold, Q3 2009 will see the first 12-month period during which S&P 500 earnings are negative.” (bold highlights mine)

Yet, with the S&P 500 up 11% over the last two weeks (+8.4% year to date and 43.8% since the March trough), many would probably impute a sharp earnings recovery for S&P component companies, and with it the US economy.

But such rationalization overlooks the obvious.

One, the S&P valuations appear to be priced for perfection.

And most importantly, as discussed in “Should We Follow Wall Street?” and “Worth Doing: Inflation Analytics Over Traditional Fundamentalism!”, stock market prices are increasingly being driven by inflation!

So any analysis which ignores the deepening significance of the inflation component in financial asset pricing would seem like ‘looking at the sun and calling it the moon’.

As Dr. Marc Faber aptly commented in a recent CNBC interview, ``The worst the economy becomes the more governments will print money and people will say, "well, the output gap will prevent inflation from occurring" Do you know what the output gap is in Zimbabwe? 99% below potential GDP and there you have the highest inflation."

This means that as global governments continue to maintain loose monetary policies, which encourages a speculative environment to revive the so-called “animal spirits”, and at the same time undertake expansion in fiscal spending, financial asset prices are most likely to exhibit dynamics which increasingly disconnects with economic and micro-fundamentals or where financial asset prices will detach from popular mainstream economic theories.

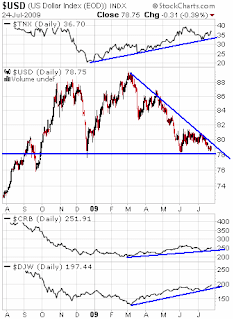

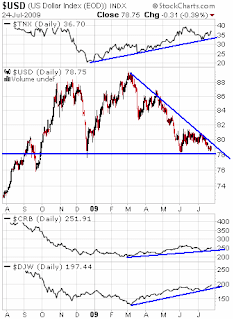

And distortions from government policies have always been vented in the currency (see Figure 2) and transmitted to various asset classes.

Figure 2: stockcharts.com: US Dollar Index At Cusp Of A Breakdown

Figure 2: stockcharts.com: US Dollar Index At Cusp Of A Breakdown

As the US dollar index sags to the point of testing the massive “descending triangle” support level, global stocks (DJW) and commodities (CRB) have been benefiting from the ongoing risk realignment-where money has apparently been shifting away from the US dollar and US sovereigns.

The yields from 10 year US Treasury Notes (TNX) has been rising to reflect on a transition from a deflationary scare and a deep recession to what mainstream deems as “transition to moderate economic recovery”.

However to my mind, the confluence of price signals in the above markets seems increasingly a manifestation of the inflation genie becoming unshackled from the proverbial oil lamp.

With the prospective breakdown of the US dollar trade weighted index, we are likely to witness the acceleration of such inflationary bias.

In his Credit Bubble Bulletin, Doug Noland says it best (bold emphasis mine),

``The problem only seems to get clearer. The maladjusted US Bubble economy is sustained by $2.0 to $2.5 Trillion of new Credit – Credit that must largely be issued or guaranteed in Washington. This reflation (a.k.a. Credit inflation/currency devaluation) drives massive flows to China, Asia and the emerging markets that have few takers other than the central banks. And as economies recover and inflationary distortions reemerge, these enormous dollar flows can be expected to foment increasing policymaker angst. Asian reflation is poised to take on a wild life of its own, forcing policymakers at some point to confront today’s reality that dollar flows are destabilizing and unmanageable. China, in particular, faces tough choices when it comes both to managing its Bubble and accumulating massive quantities of IOUs of deteriorating quality.”

More Evidences Of China’s Bubble Conditions

Indeed, China’s “run away train” markets has significantly been exuding evidences of bubble like conditions [as previously discussed in China In A Bubble, ASEAN Next Leg Up?] see Figure 3, which should pose as a dilemma for policymakers.

Figure 3: US Global Funds: Hot Money Flows And Property Bubble

Figure 3: US Global Funds: Hot Money Flows And Property Bubble

``The specter of hot money may have re-entered China. An increasing portion of China’s foreign reserve accumulation in recent months cannot be explained merely by trade inflows and foreign direct investment,” observes the US Global Investors, “betting on a strengthening Chinese currency, hot money from overseas added to the excess liquidity problem in China several years ago, and might be used again as another excuse for policy tightening in the future”

Meanwhile, the apparent euphoric mood has enchanted and drawn retail investors into the frenzied punting activities in their domestic stock market, according to Bloomberg, ``Individual investors opened 484,799 stock accounts last week, data from the nation’s clearing house showed today, the most since the five days ended Jan. 25, 2008, and almost five times this year’s low in January.”

And with a savings rate of 49.5% in 2007, according to the PBOC, (WSJ) the shifting of a substantial part of savings into the stockmarket could indeed power up a gargantuan bubble.

Hence, the transmission mechanism from US Federal Reserve inflationary monetary policies seems evident from the standpoint of momentum based international money flows which has bidded up both the stock market and the property market, while domestic policies in China have aggravated the national inflation dynamics.

And this hasn’t been limited to a China only affair.

We appear to be witnessing the same dynamics at work in Asia. As anticipated, Asia’s benchmark bourses saw a mighty succession of breakouts last week from their resistance levels in Hong Kong, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Taiwan, Pakistan, Thailand and India are likewise drifting at resistance levels gearing up for the same upside thrust.

A Bank Financed Regional Bubble?

We have argued that low systemic private sector leverage, as represented by the corporate and household sectors, fused with high savings are likely to respond materially to national monetary policies (See figure 4).

The point of our interest in the ADB chart, is that except for Taiwan and Hong Kong which saw a growth contraction in bank lending (upper left window), most of Asia, namely Singapore, Korea, and the ASEAN-4 which includes the Philippines, only saw a moderation- even in the face of the crisis.

Notice too that when ASEAN-4 policy rates had been cut from its peak in 2006 (bottom right window), bank lending growth on a year to year basis zoomed up in 2007 until it crested (upper right window) during the September 2008 Lehman bankruptcy.

Nonetheless, with artificially depressed policy rates as a function of the adaptation of myopic mainstream economics, which had been intended to spruce up consumption or the so called “aggregate demand”, bank lending growth seems poised for an explosive takeoff.

Figure 5: ADB: Importance of The Bank System In Asia

Figure 5: ADB: Importance of The Bank System In Asia

Unfortunately instead of sound investments which should translate to real economic growth, the public’s search for yield will redirect resources mostly to needless speculation.

And since bank lending has been the main credit intermediary for ASEAN (see Figure 5) or even for most of Asia’s economies we are going to possibly see a bank financed regional stock market bubble - where a big portion of the bank lending could be diverted into the stock market in an effort to extract marginal yield.

The Boom-Bust Business Cycle

And so the policy shaped investing landscape had been engineered to lure away the public from savings and into speculation and punting.

Essentially, the seed of business cycles has likewise been sown in Asia as the result of the aversion by global policymakers to face the consequences from previous policy errors.

As Professor Shawn Ritenour rightly argues in When Stimulus Does Not Stimulate (bold highlights mine),

``Artificial credit expansion — credit not funded by savings — creates the business cycle by spawning capital malinvestment. Artificial credit expansion makes many unwise investments (say, in residential and commercial real estate and financial derivatives) look profitable because of the accessibility of cheap credit, so business activity expands, manifesting itself in an inflationary boom. Bad investments, however, are not made economically sound merely because there is more money in existence. These bad investments eventually must be liquidated. The boom resolves itself in a bust whose twin children are capital consumption and unemployment. The moral of the story is that monetary inflation is not a way to sustainably generate economic prosperity.

``One thing the government does do, however, by increasing the money supply is discourage saving. This is because, as prices rise, money saved becomes worth less and less, so people are more likely to spend it on present consumption while the spending is good. Promoting consumption is the last thing we need to build up a capital stock that has been woefully depleted thanks to malinvestment. The old economic saw cuts true: there is no such thing as a free lunch, and there is no costless way to fund government spending.”

Policies that serially blows bubbles have never been sound or productive or generate sustained wealth. Moreover it serves to benefit a privileged few at the expense of the rest of the society.

Nevertheless, in an era of central banking, a policy engendered boom bust cycle is a hallmark feature that must be understood by any serious investors.

This is especially important considering the rapidly expanding role of inflation in financial asset pricing.

And Asian governments are likely to maintain present policies until the financial asset boom permeates to the real economy. From here, this would be interpreted by policymakers as having triumphantly reduced the risks of economic growth recession by reigniting economic growth through artificial credit expansion.

Sadly any perceived growth will be temporary, from where another crisis will emerge in the next few years ahead (2012 or 2013?).

For the interim, Asia’s stockmarket, under the guidance of policy induced incentives, seems likely to power up ahead.