In trying to demonstrate the importance of the distinction between causation and correlation, my favorite marketing guru Seth Godin asks “Does a ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader, or do successful bond traders go skiing in Aspen?”

This applies to political economic analysis as well.

Mainstream analysis, particularly those of the rigid Keynesian persuasion, would take the former - ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader-over the latter as the answer or correlation mistaken as causation.

Applied to the political economic sphere they would argue that in order to preserve employment at home, the policy prescription should be a mercantilistic one: inflate (currency devaluation) or impose protectionism (limiting trade via tariffs). Never mind if this flawed argument has been a discredited idea even by 18th century economists. For Keynesian mercantilists, subtraction and not addition equals prosperity (gains).

Their assumption, which mostly signifies from a reductionist perspective, oversimplifies trade as operating in fixed pie wherein one gains at the expense of the other (zero sum).

And this is supported by their rationalization which sees every economic variable as homogenous.

And through selective statistical aggregates, they derive the conclusion that only government, equipped by the knowledge on how to adjust the knobs, can rightly balance out the interest of the nation. [Applied to Seth Godin’s riddle, government should send everyone to Aspen to make them all successful bond traders!]

And also from such perspective they see employment as the only driver of businesses and of economies-forget profits, capital, productivity, property rights, market accessibility and everything else-in the rigid Keynesian world, what only counts are labor costs.

In other words, labor cost, not profits, determines investments which subsequently translate to employment. Thus for them government policies must be directed towards accomplishing this end.

It has further been alleged that the supply of labor accounts for as a vital part in determining wage levels.

The reductionism: large supply of labor equates to low wages and consequently export power.

Let’s see how true this is applied to the real world.

Since labor basically is manpower then population levels would account for as the critical denominator.

One might argue that demographic distribution per nation would be different, which is true, but the difference does not neglect the fact that population levels fundamentally determine the supply of available labor.

Here is the world’s largest population, according to Wikipedia.org,

Given the reductionism which postulates that large labor force equates to low wages, then we should expect these countries, including the US and Japan to have the lowest wage rates in the world!

Yet even without looking at wage statistics we know this to be patently false (as seen from the bigger picture)!

Since wage levels are different per nation or per locality, perhaps the best way to gauge wages would be to use minimum wages as a yardstick.

Minimum wage account for as the national mandated minimum pay levels that are directed towards the lowest skilled workers.

Going back to the mercantilist postulate, since the largest population (largest pool of available labor) per continent belongs to Asia,...

...then the mercantilist logic implies that the lowest wages should be in Asia. Chart courtesy of Geo Hive (xist.org).

Yet according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), based on median minimum wages per country (US $PPP) the lowest wages would be in South East Europe and the CIS!

Asian wages are even higher than Africa and Southeast Europe and the CIS. Another disconnect!!

In addition, if broken down on a per country basis, based on the level of minimum wages in 2007 (PPP US$).... (again from ILO)

We would find that NONE of the largest or most populous countries (all in red arrows) are at the lowest echelon, except for Bangladesh and the Russian Federation seen at the lowest decile. (Yet the latter two are NOT export giants)

In pecking order, China, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria Pakistan and India are mostly situated at the upper segment of the lower half of the graph.

Meanwhile the Philippines can be seen on the higher second quartile, and the US having the highest minimum wages (among the highest populated nations), along with European countries.

So what this proves?

There is hardly any correlation between population levels (supply of labor) and wage levels! The assertion that supply of labor equals low wages is outrageously naive and inaccurate!

And let us further examine how these minimum wage levels impact exports. The following chart of the world’s largest exporters is from Wikipedia.org

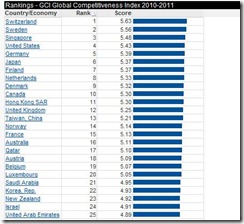

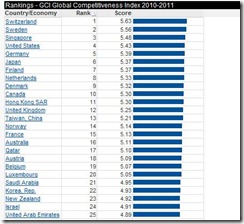

And I would also include global competitiveness as measured by the World Economic Forum (Global Competitiveness report)

So what do we see?

We see a strong correlation between the world’s biggest exporters and the most competitive nations. And one might add to that HIGH minimum wages!

While it would be tempting to argue that high minimum wages equals strong competitiveness/exports, we would be falling for the same post hoc argument trap of misreading correlation as causation like those employed by rigid Keynesians.

The real answer to such wage disparity is the high standards of living in developed economies which arises from the greater capital stock (or productive assets in the economy) and a higher productivity of the citizenry.

As Professor Donald J. Boudreaux explains, (bold highlights mine, emphasize his)

Low-wage labor is generally not low-cost labor. The reason is that the productivity of low-wage workers in China and other developing countries is much lower than is the productivity of workers in America. While low-wage foreigners outcompete high-wage Americans at many low-skill, routine, and repetitive tasks, high-wage Americans can (and do) outcompete low-wage foreigners in those tasks that can be performed efficiently only in advanced economies that are full of the machinery and intricate infrastructure – physical, legal, and cultural – that raise wages by raising worker productivity

In short, high American wages aren’t a disadvantage; they are a happy reflection of the fact the typical American worker is a powerhouse of production.

In short to argue from a wrong premise would mean wrong conclusions.

Why?

Because for politically blinded people, their intuitive tendency is to selectively pick on events or data points (data mining, e.g. low value low skill industries, China) and deliberately misinterpret them (to create a strawman-China's low wages stealing American and Filipino jobs) in order to fit all these into their desired conclusions (cart before the horse reasoning-erect trade barriers).

They similarly deploy false generalizations based on the perceived defects interpreted as a general condition (fallacy of composition-low wages equals export strength).

These represent not only as sloppy ‘blind spot’ thinking but likewise, a reductio ad absurdum or a conclusion based on the reduction to absurdity.

Caveat emptor.