Since every central bank of major economies has been inflating, it’s a question of which central bank has been inflating the most. The obvious answer is the US. The US has not only been inflating her economy, she has basically been inflating the rest of the world.

A US Dollar rally can occur and can be sustained once the US withholds inflationism. But $64 trillion question is: Can they afford the consequences?

Like in early 2010, experts and officials babbled about “exit strategies” as the US economy’s recovery advanced, something which we debunked as a Poker Bluff[1]. Yet 10 months later, the Fed re-engaged in Quantitative Easing 2[2] citing “low consumer spending” and “unemployment” as an excuse even as the US moved out of the recession in June of 2009th[3].

The mainstream doesn’t get it or has stubbornly been denying this.

Quantitative Easing or euphemistically called Credit Easing isn’t about the economy but about buttressing politically the US government and the banking system.

As Mises Institute Lew Rockwell writes[4],

Another truth is that the Fed doesn’t really care about inflation as much as it cares about the solvency of the banking and financial systems. Bernanke would drive us right into hyperinflation to save his industries. Savers living on pensions just don’t have the political clout to stop the money machine.

US housing has still been struggling. Since a substantial segment of the banking system’s balance sheets have been stuffed with US mortgages, then QE 1.0 and 2.0 has managed to keep these afloat but has, so far, failed to strongly revive the US housing market[5].

Under enfeebled housing conditions, a failure to continue with the QE amplifies the risks of falling housing prices thereby jeopardizing the fragile state of the US banking system.

Most importantly, the US Federal Reserve has been buying US Treasuries which means the US central bank has been funding the profligacy of US government.

Yet much of US treasury has also been substantially held by the foreign governments.

However, there are signs that the interest to hold US debt has been waning.

According to Economic Times India[6]

China, the biggest foreign holder of US debt has trimmed its portfolio to $1.15 trillion to diversify its foreign reserve portfolio to avoid risks.

China reduced its US Treasuries portfolio by $5.4 billion to $1.15 trillion in January, according to the data released by the US Treasury Department on Wednesday.

It is the third straight month of net selling after China's holdings of US debt reached a peak of nearly $1.18 trillion in October 2010.

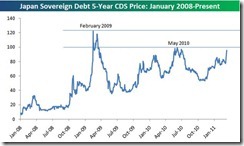

If the Japan repatriation trade proves to be a real event risk, then this could even further dampen interest to support US debt.

With substantial foreign held US debt maturing over the next 36 months[7], if foreign governments withhold from buying, will the US accept higher interest rates?

Given the ideological background and the path dependency by the incumbent monetary authorities, the answer is a likely NO!

The US government can’t simply put her fragile banking system at risks, and thus, we can bet that QE 3, 4, 5 to the nth, will likely occur until the market recoils from these.

The above doesn’t even include the financial conditions of wobbly states and municipalities.

Financial conditions of US states have been plodding[8] while Municipal bonds, following a huge meltdown, has also been floundering. The rally in the Muni bonds have not erased the losses.

Controversial analyst Meredith Whitney, who recently presaged “50 to 100 sizable defaults to the tune of “hundreds of billions of dollars worth of defaults”[9], has been constantly under fire by the mainstream, for such prognosis. She has even been summoned by a US Congressional Panel. Anyone who goes against the government appears to be subject to censorship or political harassment.

The point is: given all these fragile conditions, will the Ben Bernanke led US Federal Reserve bear the onus of withdrawing, what has given Bernanke and the Fed an artificial aura of success?

[1] See Poker Bluff: The Exit Strategy Theme For 2010, January 11, 2011

[2] CNN Money.com QE2: Fed pulls the trigger, November 3, 2010

[3] Reuters.com Recession ended in June 2009: NBER, September 20, 2010

[4] Rockwell, Llewellyn H. Is QE3 Ahead?, Mises.org, March 18, 2011

[5] Northern Trust, Sales of Existing Homes Moved Up, But Median Price Establishes New Low, February 23, 2011 and

Food and Energy Prices Lift Wholesales Prices, But Pass through to Retail Prices is Key, March 16, 2011

[6] Economic Times India, China continues to trim its US debt to avoid risks, March 18, 2011

[7] Osborne, Kieran U.S. Government: Evermore Reliant on Foreign Investors Merk Investments, March 15, 2011

[8] Center on Budget Policies and Policy Priorities, States Continue to Feel Recession’s Impact, March 9, 2011

[9] New York Times, A Seer on Banks Raises a Furor on Bonds, February 7, 2011