I talked about swelling signs of distribution before my dsl connection cut me off.

In spite of this week’s majestic breakaway run by the Phisix and a robust performance by ASEAN peers, there seems to be more evidence of global distribution in motion. Some would call this divergence or disconnect.

So far, ASEAN has been on the positive end and converging.

As of Friday’s close, the Philippine Phisix (Orange line) continues to provide leadership in the region up by .95% over the week or 19.69% nominal currency gains year-to-date.

Such remarkable advance accounts for an average monthly return of about 5.6%. At the current rate of gains, the Phisix 10,000 in 2013 is still very much in play. Of course that’s unless some exogenous event, such as the growing risks of a crisis in Japan, may prove to be an obstacle to the current manic phase.

Our regional counterparts have also been showing signs of buoyancy. Indonesia’s JCI (yellow) has been a distant second to the Phisix after this week’s 1.24% advance which accrues to a 15.79% return year-to-date. Thailand’s SET (red orange) has recaptured double digit gains up 1.19 for the week or 11.3% returns for 2013. Thailand’s SET, which earlier had been neck to neck with the Phisix, has been derailed by interventions from regulators who recently raised collateral requirements for margin trades. Malaysia’s KLCI (green) has officially popped to the positive side (charts from Bloomberg)

The Philippine Mania in Motion

In the Philippines, the manic phase seems in full motion.

The manic phase as aptly described by Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in chronicle of their 8 centuries of financial, banking and economic crises in This Time is Different[1]:

The essence of this-time-is-different syndrome is simple. It is rooted in the firmly held belief that financial crises are things that happen to other people in other countries at other times; crises do not happen to us here and now. We are doing things better, we are smarter, we have learned from our past mistakes. The old rules of valuation no longer apply. The current boom, unlike the many booms that preceded catastrophic collapses in the past (even in our country), is built on fundamentals, structural reforms, technological innovation, and good policy. Or so the story goes

A good example is the embarrassing gaffe by one of the leading broadsheets for publishing in the headlines a bogus or spoof pictorial of Time magazine featuring the Philippine President[2]. While the Philippine president did land in the Time’s list of 100 most influential people, he failed to grace the magazine’s cover.

But the booboo shows exactly how media has functioned as mouthpieces for the government.

More than that, mainstream media has been quick to hype on the supposed economic boom from alleged “good policies”.

Yet local media hardly covered World Bank’s latest implicit admission of emerging Asia’s bubble in progress, where the World Bank supposedly warned of “demand-boosting measures may now be counterproductive” (euphemism for asset bubbles) and that capital flows “may amplify credit and asset price risks”. Thus the World Bank prescribes that emerging Asia should put a break on easing policies[3].

In addition, local central bank chief also got accolades for taking the Philippine economy to the “stars”.

The Wall Street Journal Blog reports[4]

Philippine’s central bank chief Amando Tetangco has taken to star gazing, of a kind, to guide the nation’s economy and so far he likes what he sees.“The star of strong GDP growth and the star of low inflation,” Mr. Tetangco says in an upbeat interview during the Spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund. “This alignment of the stars is further strengthened by a healthy balance of payments surplus,” he said.But it’s not all about the cosmic. The central bank boss also likes to draw on physics to explain how the quick growing South East Asian economy is faring between surging inward capital flows and risks posed by a sluggish global economy.“I am not an astrologer but sometimes it is better to describe things like this,’ he says. Physics tell it best.

Amazing hubris.

Mr. Tetangco didn’t say it explicitly but his implication is that “healthy balance of payments surplus” serves as shield against a crisis.

Mr. Tetangco does not distinguish between the various types of crises. While it is true that most crises has had the character of balance of payments deficits functioning as triggers to imbalances earlier accumulated that led to balance of payment or currency or exchange rate crises[5], there are other forms of crises.

They fall under the categories of debt crises, banking crises and serial defaults[6] (Reinhart, Rogoff 2011).

The above are examples of non-balance of payment crises. Particularly they are examples of two banking crises and a sovereign debt crisis.

Japan’s domestic asset bubbles[7] in the 1980s had been forged amidst current account surpluses. The 1990 bust led to a banking and economic crisis that still lingers 3 decades after…today.

UK’s secondary banking crisis of 1974-1975 also emanated from a prior property boom or the “last hurrah of the post war property boom” as noted by Wikipedia[8], which likewise has had a current account surplus going into the crisis.

Russia’s 1998 debt crisis[9] from unwieldy fiscal deficits that led to a massive government debt build-up was exacerbated by crashing commodity prices that led to a sovereign debt default. Going into the crisis, Russia posted current account surpluses from oil and commodity export receipts.

False assumptions and illusions brought about by a credit boom will eventually be unmasked.

Such basking in narcissistic self-attribution glory reminds me of the Bank of Cyprus[10], one of the largest financial institutions of the recently stricken Cyprus.

In the mistaken perception that Cyprus successfully eluded the Euro crisis, and that they had become “immune” or has “decoupled” from the Eurozone, the Bank of Cyprus became a recipient of as many as 9 prestigious awards from February 2011 until September 2012[11]. As the Cyprus crisis emerged in March of 2013 or 5 months after the last award, depositors of the Bank of Cyprus may lose up to 60% of their savings[12] to bail-in the banks. Yes this is an example of a bizarre twist of fate.

I may add that for the mainstream, bubbles are after the fact knowledge.

As author Philip Coggan, and Economist contributor under the pen name of Buttonwood notes[13],

Ireland and Spain looked OK on government debt-to-GDP before the crisis but then they didn't.

And one of the haughtiest allusions has been to attribute policy success as “physics”. Such are patent symptoms of bubble mentality.

Positivist policies shaped by mathematical models will hardly extrapolate to “good policy”.

The presumption that natural science as equivalent to social science is a mistake. This has been based on faith or dogma and ego rather than reality. One cannot build on policies based on simplistic assumptions and mathematical aggregates when the fact is that the world is highly complex and where knowledge is distinct, diffused and fragmented. And because of such complexity, econometrics and statistical equations cannot model individual preferences, knowledge, emotions and value scales, since there is nothing constant in human action, especially with people’s interaction with each other or with the environment.

Statistics are historical artifacts, relying on them means to wrongly assume the same circumstances will take hold in the future. Statistics and math alone cannot precisely foretell of the future. And policies based on statistics and math will be met with unintended consequences.

As the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises explained[14]

The natural sciences too deal with past events. Every experience is an experience of something passed away; there is no experience of future happenings. But the experience to which the natural sciences owe all their success is the experience of the experiment in which the individual elements of change can be observed in isolation. The facts amassed in this way can be used for induction, a peculiar procedure of inference which has given pragmatic evidence of its expediency, although its satisfactory epistemological characterization is still an unsolved problem.The experience with which the sciences of human action have to deal is always an experience of complex phenomena. No laboratory experiments can be performed with regard to human action. We are never in a position to observe the change in one element only, all other conditions of the event remaining unchanged. Historical experience as an experience of complex phenomena does not provide us with facts in the sense in which the natural sciences employ this term to signify isolated events tested in experiments. The information conveyed by historical experience cannot be used as building material for the construction of theories and the prediction of future events. Every historical experience is open to various interpretations, and is in fact interpreted in different ways.The postulates of positivism and kindred schools of metaphysics are therefore illusory. It is impossible to reform the sciences of human action according to the pattern of physics and the other natural sciences. There is no means to establish an a posteriori theory of human conduct and social events. History can neither prove nor disprove any general statement in the manner in which the natural sciences accept or reject a hypothesis on the ground of laboratory experiments. Neither experimental verification nor experimental falsification of a general proposition is possible in its field.

Growing Distribution or Divergences

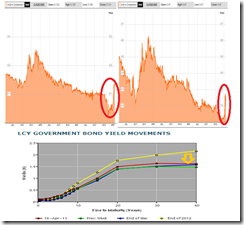

Finally signs are pointing to a growing dynamic of divergence dynamic among global asset markets.

Among major equities, US and Japan continues to post gains even as much of the world appears to turning over. Of course this is with the exception of ASEAN.

Despite the material year to date 9.1% gains by the S&P 500, internally the sectoral performance has diverged. Health Care, Consumer staples, utilities cyclicals and financials have boosted the S&P while materials, technology energy and industrials have weighed on the index. Perfchart from stockcharts.com

While I believe that much of the world will likely endure more pangs from growing signs of financial market weakness, it is unclear whether this will also impact the ASEAN markets whose mania phase has been running in full throttle.

This is of course unless there would be a major external financial smash up that could trigger a domino effect.

Nonetheless as market weaknesses becomes more pronounced, we should expect global authorities to jettison their “exit” meme that was really never meant to be and shift their tones to “dovish” or advocate on more inflationism.

The recent quasi crash of gold-commodities which has been used by the mainstream as pretext to clamor for more central bank inflationism partly validates my earlier views[15].

And in contrast to the common reaction where crashes would lead to a loss of confidence and a ripple effect or a panic contagion, the quasi crash in paper gold at Wall Street, prompted for a near simultaneous frenzied or panic buying of gold in the physical markets[16] across the globe which also attained a milestone. For instance one day sales of US gold mint reached a landmark high[17].

In short, gold-commodity markets have also been diverging.

Yet this is hardly about “deflation” under the context of “aggregate demand”, and “liquidity traps” but about the dynamics of bubble cycles.

Navigating today’s treacherous market requires prudence, as incessant interventions has rendered markets highly susceptible to magnified volatility and whose state of fragility raises the risks of bubble busts, whose trigger may emanate from anywhere.

[1] Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff This Time is Different p.15 Princeton Press 2009

[2] Rappler.com Inquirer: Fake Aquino Time cover ‘honest mistake’ but... April 20, 2013

[3] See World Bank: Developing Asia Should Put a Brake on Easing Policies April 16, 2013

[4] Wall Street Journal Blog Philippines Stars Line Up, Thailand Looks for a Lady’s Touch April 19, 2013

[5] Wikipedia.org Currency crisis

[6] Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis, Harvard University August 2011

[7] Wikipedia.org Japanese asset price bubble

[8] Wikipedia.org 1998 Russian financial crisis

[9] Wikipedia.org 1998 Russian financial crisis

[10] Wikipedia.org Bank of Cyprus

[11] See Example of the Mania Phase: Awards Received by the Bank of Cyprus March 27, 2013

[12] Bloomberg.com Bank of Cyprus Clients May Lose Up to 60% on Deposits April 2, 2013

[13] Philip Coggan Buttonwood Rotation schmotation April 18, 2013 Economist.com

[14] Ludwig von Mises 1. Praxeology and History Chapter II. The Epistemological Problems of the Sciences of Human Action Human Action Mises.org

[15] See I Told You So: Gold Slump Used as Justification for MORE QE April 17, 2013

[16] See Gold Price Crash Spurs Boom in Physical Gold Markets April 18 2013

[17] Frank Holmes Gold Buyers Get Physical As Coin and Jewelry Sales Surge US Global Investors April 19, 2013