Now experience is not a matter of having actually swum the Hellespont, or danced with the dervishes, or slept in a doss-house. It is a matter of sensibility and intuition, of seeing and hearing the significant things, of paying attention at the right moments, of understanding and co-ordinating. Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him. It is a gift for dealing with the accidents of existence, not the accidents themselves. By a happy dispensation of nature, the poet generally possesses the gift of experience in conjunction with that of expression.—Aldous Huxley, Texts and Pretexts (1932), p. 5

You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you mad. ― Aldous Huxley

Last week I wrote[1]: (bold original)

Ultimately it will be the global bond markets (or an expression of future interest rates) that will determine whether this week’s bear market will morph into a full bear market cycle or will get falsified by more central bank accommodation.

US Treasury Yields Surges!

The surge of yields of US treasury will have interesting implications on global markets.

According to the mainstream[2], Friday’s “robust” jobs data in the US supposedly would extrapolate to a so-called “tapering” or an eventual reduction of monetary policy accommodation by the US Federal Reserve. Such has been imputed as having “caused” the monumental spike US treasury yields from the 5, 10 and 30 year maturity spectrum.

But this narrative represents only half the picture.

Previously there has been a broad based boom in US financial assets (real estate, stocks and bonds). This has been changing.

Given the Fed’s accommodative policies, a financial asset boom represents symptom an inflationary boom. Such boom appears to have percolated into the real economy which has been reflected via the ongoing recovery in commercial and industrial loans which approaches the 2008 highs (upper window)[3]. Consumer credit has also zoomed beyond 2008 highs[4]. This means that the pressure for higher has been partly a product of greater demand for credit.

But treasury yields have been rising since July 2012. Treasury yields have been rising despite the monetary policies designed to suppress interest rates such as the US Federal Reserve’s unlimited QE in September 2012, Kuroda’s Abenomics in April 2013 and the ECB’s interest rate cut last May.

Rising treasury yields accelerated during the second quarter of this year, which has now been reflected on yields of major economies, not limited to G-4. And rising global yields as pointed out last week, coincides with recent convulsions in global stock and bond markets, ex-US currencies, and increasing premiums in Credit Default Swaps.

What Rising UST Yields Mean

The spike in US Treasury yields has broad based implications.

Treasury yields, particularly the 10 year note[5], functions as important benchmark which underpins the interest rates of US credit markets such as fixed mortgages and many longer term bonds.

Rising treasury yields means higher interest rates for US credit markets.

Treasury yields also serves as the fundamental financial market guidepost, via yield spreads[6], towards measuring “potential investment opportunities” such as international interest rate “carry trade” arbitrages.

The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that the stock of global equity, bond and loan markets as of 2nd Quarter of 2012 has been at US$225 trillion[7]

Market capitalization of global equities at $50 trillion signifies a 22% share of the total. The $100 trillion bond markets, particularly government ($47 trillion), Financial sector bonds ($42 trillion) and Corporate bonds ($11 trilllion) constitute 44%, while securitized ($13 trillion) and non-securitized loans ($ 62 trillion) account for 33% of the global capital markets.

Said differently, interest rate sensitive bond and loans markets represent 78% share of the global capital markets as of the 2nd quarter of 2012.

And as interest rates headed for zero-bound, the global bond and loan markets grew by 5.6% CAGR since 2000, this compared with equities at 2.2% CAGR.

Higher interest rates translate to higher costs of servicing debt for interest rate sensitive global bond and loan markets. Theoretically, 1% increase in the $175 trillion bond and loan markets may mean $1.75 trillion worth of additional interest rate payments. The higher the interest rate, the bigger the debt burden.

Moreover, sharply higher UST yields will likely reconfigure ‘yield spreads’ drastically on a global scale to correspondingly reflect on the actions of the bond markets of the US and the other major developed economies.

Such adjustments may exert amplified volatilities on many global financial markets including the Philippines.

For instance, soaring US bond yields have already been exerting selling strains on the Philippine bond markets as I have been predicting[8].

Philippine 10 year bond yields[9] jumped 35 bps on Friday or 13 bps from a week ago.

And no matter how local officials earnestly proclaim of their intent or goal to preserve the low interest rate environment[10], a sustained rise in local bond yields will eventually compel policymakers to either fight bond vigilantes with a domestic version of bond buying program which amplifies risks of price inflation (which also implies of eventual higher interest rates), or allow policies to reflect on bond market actions.

Worst, a sustained rise in international bond yields, which reduces interest rate arbitrages or carry trades, may exacerbate foreign fund outflows. Such would prompt domestic central banks of emerging market economies, such as the Philippines, to use foreign currency reserves or Gross International Reserves (GIR) to defend their respective currencies; in the case of Philippines, the Peso.

‘Record’ surpluses may be headed for zero bound or even become a deficit depending on the speed, degree and intensity of the unfolding volatilities in the global bond markets.

Yet any delusion that the yield spreads between US and Philippine bonds should narrow towards parity, which would imply of the equivalence of creditworthiness of the largest economy of the world with that of an emerging market, will be met with harsh reality which a tight money environment will handily reveal.

The new reality from higher bond yields in developed economies are most likely to get reflected on “yield spreads” relative to emerging markets via a similar rise in yields.

Yet many banks and financial institutions around the world are proportionally vulnerable to losses based on variability of interest rate risk exposures particularly via fixed-rate lending funded that are funded by variable-rate deposits.

Importantly, the balance sheets of public and private financial institutions are highly vulnerable to heavy losses as bond yields rise.

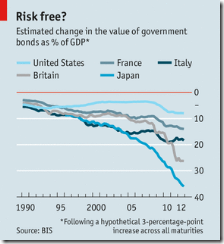

As the Economist observed[11], (bold mine)

The immediate threat to banks is a fall in the market value of assets that banks hold. As yields of government bonds and other fixed-income securities rise, their prices fall. Because the amounts of outstanding debt are so large, the effects can be big. In its latest annual report the Bank for International Settlements, the Basel-based bank for central banks, reckons that a hypothetical three-percentage-point increase in yields across all bond maturities could result in losses to all holders of government bonds equivalent to 15-35% of GDP in countries such as France, Italy, Japan and Britain

What has been categorized as “risk free” now metastasizes into a potential epicenter of a global crisis.

It would be foolish or naïve to shrug at or dismiss the prospects of losses to the tune of 15-35% of GDP. These are not miniscule figures, and my guess is that they are likely to be conservative as these figures seem focused only on bond market losses.

While a sustained increase in the price of credit should translate to eventually lesser demand for credit, as the cost of capital rises that serves to restrict or limit marginal capital or the viability or profitability of projects, what is more worrisome is that “because the amounts of outstanding debt are so large” or where formerly unprofitable projects became seemingly feasible due high debts acquired from the collective credit easing policies by global central banks, the greater risks would be the torrent of margin calls, redemptions, liquidations, defaults, foreclosures, bankruptcies and debt deflation.

Government Debt and Derivatives as Vulnerable Spots

And such losses will apply not only to the private sector but to governments as well.

I pointed out last week of a report indicating that many central banks has been hurriedly offloading “record amount of US debt”. As of April 2013, according to US treasury data[12], total foreign official holders of US Treasury papers, led by China and Japan was $5.671 trillion.

This means that the $5.671 trillion foreign official holders (mostly central banks and sovereign funds) of USTs have already been enduring stiff losses. This is likely to encourage or prompt for more selling in order to stem the hemorrhage. I would suspect that the same forces have played a big role in this week’s UST yield surge.

Additionally, the propensity to defend domestic currencies from the re-pricing of risk assets via dramatic adjustments in yield spreads means that the gargantuan pile up of international reserves are likely to get drained for as long as the rout in the global bond markets continues.

As of April, the stock of US treasury holdings of the Philippine government (most of these are likely BSP reserves) has likewise been trending lower. That’s a month before the bloodbath. It would be interesting to see how developments abroad will impact what mainstream sees as “positive fundamentals”—or statistical data compiled based on a period of easy money.

I also previously pointed out[13] that of the $633 trillion global OTC derivatives markets as of December 2012, interest rate derivatives account for $490 trillion or 77.4%

The asymmetric risks from interest rate swap transactions as defined by Investopedia.com[14]

A plain vanilla interest-rate swap is the most basic type of interest-rate derivative. Under such an arrangement, there are two parties. Party one receives a stream of interest payments based on a floating interest rate and pays a stream of interest payments based on a fixed rate. Party two receives a stream of fixed interest rate payments and pays a stream of floating interest rate payments. Both streams of interest payments are based on the same amount of notional principal.

Sharply volatile bond markets, in the backdrop of higher rates, increases the rate of interest payments and equally increases the risk potential of financial losses particularly on the second party who “receives a stream of fixed interest rate payments and pays a stream of floating interest rate payments”. And the corollary from the ensuing amplified losses may imply of magnified credit and counterparty risks. And we are talking of a $490 trillion market.

Yet it is not clear how much leverage has been accumulated in the US and global fixed income markets, fixed income based mutual fund markets as well as ETFs via risk exposures on Corporate bonds, Municipal bonds, Mortgage Backed Securities, Agencies, Asset Backed Securities and Collateral Debt Obligations[15], as well as, emerging market securities.

Will a sharp decline in fixed income collateral values prompt for higher requirements for collateral margins? Or will it incite a tidal wave of margin calls? How long will it last until one or more major US or global institutions “cry wolf”?

Rising interest rates in and of itself should be a good thing since this should rebalance people’s preferences towards savings and capital accumulation, the difference is that prolonged period of easy money policies has entrenched systematic misallocation of resources which has engendered highly distorted and maladjusted economies, artificially ballooned corporate profits and valuations, and has severely mispriced markets by underpricing risks.

The bottom line: If the tantrum in the bond market persists or even escalates, higher bond yields in developed economies will not only reflect on a process of potential disorderly adjustments for “yield spreads” of emerging markets such as the Philippines—under a newfangled renascent regime of the bond vigilantes—but they are likely to negatively impact the growth of the intensely leveraged, low interest rate dependent $225 trillion capital markets, as well as, the $490 trillion derivative markets.

It is imperative to see bond markets stabilize before ploughing into any type of investments.