I recently pointed out that October brought upon us the reality of real time crashes—a dynamic we have not seen since 2008.

In spite of the ECB-PBOC-BOJ fueled stock market boom, crashes seem to be still haunting global markets

From Reuters:

Saudi Arabia blocked calls on Thursday from poorer members of the OPEC oil exporter group for production cuts to arrest a slide in global prices, sending benchmark crude plunging to a fresh four-year low.Brent oil fell more than $6 to $71.25 a barrel after OPEC ministers meeting in Vienna left the group's output ceiling unchanged despite huge global oversupply, marking a major shift away from its long-standing policy of defending prices.This outcome set the stage for a battle for market share between OPEC and non-OPEC countries, as a boom in U.S. shale oil production and weaker economic growth in China and Europe have already sent crude prices down by about a third since June.

The sustained crash in oil prices (WTI left, Brent right) has just been amazing

On the one hand, we see record stocks in developed economies backed by record debt. On the other hand, we see crashing commodities led by oil prices. So the world has been in a stark divergence in terms of market actions.

Prior to the US prompted global crisis of 2008, divergence in the US housing and stocks heralded the (2008) crash. US housing began to decline in 2006 as stock markets soared to record highs. When the periphery (housing) hit the core (banking and financial system), the entire floor caved in.

Today’s phenomenon (crashing commodities as well as crashing Macau stocks and earnings) runs parallel to the 2008 crash, except that this comes in a global dimension.

Bulls rationalize that lower oil price benefit consumption. This is true. Theoretically. But what they didn’t explain is why oil prices have collapsed and now nears the 2008 levels. Has this been because of slowing demand (which ironically means diminishing consumption)? If so why the decline in consumption (which contradicts the premise)?

Or has this been because of excessive supply? Or a combination of both? Or has a meltdown in oil prices been a symptom of something else--deflating bubbles?

Yet how will consumption be boosted? Is consumption all about oil?

If economies like Japan-Eurozone and China have been floundering because of too much debt or have been hobbled by balance sheet problems that necessitates for central bank interventions, how will low oil prices improve demand? Well my impression is that low oil prices may alleviate only the consumer’s position, but this won’t justify a consumption based boom.

Again the problem seems to be why prices are at current levels?

Again the problem seems to be why prices are at current levels?

From the production side, what collapsing oil prices means is that oil producing emerging markets will likely get hit hard…

The above indicates nations dependent on oil revenues.

Oil production share of GDP won’t be much a concern if not for the role of domestic political spending (welfare state) which oil revenues finance…

At current levels, almost every fiscal position (welfare state) of oil producing nations will be in the red.

This simply means several interrelated variables, namely, economies of these oil producing nations will see a sharp economic slowdown, the ensuing economic downturn will bring to the limelight public and private debt problems thereby magnifying credit risks (domestic and international), a downshift in the economy would mean growing fiscal deficits that will be reflected on their respective currencies where the former will be financed and the latter defended by the draining of foreign exchange reserves or from external borrowing and importantly prolonged low oil prices and expanded fiscal deficits would eventually extrapolate to increased incidences of Arab Springs or political turmoil.

But the implications extend overseas.

I have pointed out in the past that any attempt to use oil prices as ‘weapon’ (predatory pricing) to weed out market based competitors, particularly Shale oil, will fail over long term

But over the interim, collapsing oil prices will have nasty consequences for the US energy sector, particularly the downscaling, reduction or cancellation of existing projects and most importantly growing credit risks from the industry's overleveraging.

The Shale industry has been a part of the US Fed inflated bubble.

Notes the CNBC: (bold mine)

Employment in the oil and gas sector has grown more than 72 percent to 212,200 in the last decade as technology such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing have made it possible to reach fossil fuels that were previously too expensive to extract. In order to fund the rapid growth, exploration and production companies have borrowed heavily. The energy sector accounts for 17.4 percent of the high-yield bond market, up from 12 percent in 2002, according to Citi Research.

Falling oil prices will increase credit risks of US energy producers, from the Telegraph

Based on recent stress tests of subprime borrowers in the energy sector in the US produced by Deutsche Bank, should the price of US crude fall by a further 20pc to $60 per barrel, it could result in up to a 30pc default rate among B and CCC rated high-yield US borrowers in the industry. West Texas Intermediate crude is currently trading at multi-year lows of around $75 per barrel, down from $107 per barrel in June.

Collapsing oil prices will thus prick on the current Shale oil bubble.

But the basic difference between oil producing welfare states and debt financed market based Shale oil producers have been in the political baggage that the former carries.

The current bubbles seen in the energy sector implies that inefficient producers today will simply be replaced by more efficient producers overtime. The industry will experience a painful market clearing adjustment process but Shale energy won’t go away.

The damage will be magnified in terms of political dimensions of welfare states of oil producing nations.

And as previously noted, the non-cooperation or perceived persecution of rival oil producing nations will have geopolitical consequences. There may be attempts by rogue groups financed by rival nations to disrupt or sabotage production lines in order to forcibly reduce supplies. This will only heighten geopolitical risks.

In addition, since forex reserves of producing nations will be used to finance domestic welfare state and defend the currency, such will reduce liquidity in the system

As the Zero Hedge duly notes: (bold italics original)

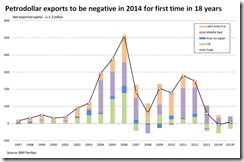

As Reuters reports, for the first time in almost two decades, energy-exporting countries are set to pull their "petrodollars" out of world markets this year, citing a study by BNP Paribas (more details below). Basically, the Petrodollar, long serving as the US leverage to encourage and facilitate USD recycling, and a steady reinvestment in US-denominated assets by the Oil exporting nations, and thus a means to steadily increase the nominal price of all USD-priced assets, just drove itself into irrelevance.A consequence of this year's dramatic drop in oil prices, the shift is likely to cause global market liquidity to fall, the study showed.This decline follows years of windfalls for oil exporters such as Russia, Angola, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria. Much of that money found its way into financial markets, helping to boost asset prices and keep the cost of borrowing down, through so-called petrodollar recycling.But no more: "this year the oil producers will effectively import capital amounting to $7.6 billion. By comparison, they exported $60 billion in 2013 and $248 billion in 2012, according to the following graphic based on BNP Paribas calculations."In short, the Petrodollar may not have died per se, at least not yet since the USD is still holding on to the reserve currency title if only for just a little longer, but it has managed to price itself into irrelevance, which from a USD-recycling standpoint, is essentially the same thing.According to BNP, Petrodollar recycling peaked at $511 billion in 2006, or just about the time crude prices were preparing to go to $200, per Goldman Sachs. It is also the time when capital markets hit all time highs, only without the artificial crutches of every single central bank propping up the S&P ponzi house of cards on a daily basis. What happened after is known to all..."At its peak, about $500 billion a year was being recycled back into financial markets. This will be the first year in a long time that energy exporters will be sucking capital out," said David Spegel, global head of emerging market sovereign and corporate Research at BNP.Spegel acknowledged that the net withdrawal was small. But he added: "What is interesting is they are draining rather than providing capital that is moving global liquidity. If oil prices fall further in coming years, energy producers will need more capital even if just to repay bonds."In other words, oil exporters are now pulling liquidity out of financial markets rather than putting money in. That could result in higher borrowing costs for governments, companies, and ultimately, consumers as money becomes scarcer.

It’s interesting to note how some major oil producers have seen some major selling pressures in their stock markets…

Saudi Arabia’s Tadawul

The pressures have likewise been reflected on their currencies: USD-Kuwait Dinar, USD-Saudi Riyal and Nigeria’s Naira.

For the populist Philippine G-R-O-W-T-H story, if the Middle East runs into economic and financial trouble or if the collapse in oil prices triggers the region’s bubble to deflate, then how will this translate into OFW “remittance” growth? The largest deployment of OFWs has been in the Middle East. Or is it that OFWs are immune to the region’s woes?

Interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment