Keynesianism has the markings of a religion. It has a confession: "Fiat money overcomes recessions." It has an agenda: salvation by economic growth. It has a doctrine of omniscience: monetary central planning. It has a priesthood: Ph.D-holding economists. It has evangelism: Congress, the universities, and the mainstream media.—Gary North

In this issue:

Phisix: BSP’s Response to Peso Meltdown: Raise Banking Reserve Requirements

-Economic Repression Equals Smuggling and the Informal Economy

-The Real Score Behind Philippine Peso and Balance of Payment

-Philippine Bonds Dissatisfied with BSP’s Actions

-Media Cheers as the BSP Tweaks Reserve Ratio

-Assailing the Informal Economy: The Philippines Bans Coin Savings

-Rotation or Risk ON or Bull Trap???

Phisix: BSP’s Response to Peso Meltdown: Raise Banking Reserve Requirements

The Philippine Peso, which closed at 44.88 against the US dollar in the week ending March 28th, shaved off two thirds of the significant 1.43% loss accrued from last week’s meltdown. The rally in the peso came in tandem with a marginal rebound in Philippine 10 year bonds where yields slipped by 10 bps to 4.471% as the Phisix eked out a .32% gain.

Although this week’s rally somewhat resonated a “Risk On” environment, behind all these appears to be the substantial interventions by the Philippine central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) which culminated with Thursday’s raising of reserve requirements on the banking system[1] or what the mainstream labels as “tightening”.

Such action confirms on my narratives of the domestic risk environment where “today’s operating environment has been vastly different from the heydays of 2013. Then the Phisix boom has been in confluence with zero bound rates, low statistical consumer price inflation figures and a firming Peso. In essence, the Phisix sailed in the tailwind of a Risk ON easy money landscape. Today, tailwind has morphed into headwind—falling peso, rising yields and even higher statistical price inflation. Yet stock market punters have been desperately forcing to reinstate or resurrect the past.”[2]

Economic Repression Equals Smuggling and the Informal Economy

I watched in engaging curiosity how the mainstream has desperately been scurrying to explain on the unexpected sluggishness of the peso which has gone beyond the entrenched popular perception of the supposed insuperability of the Philippine economy.

One interesting view has been to raise “smuggling” as the culprit of the peso’s predicament.

Highly paid experts from foreign institutions suggests that “import data may have been understated since as early as 2007”, partly because of smuggling which has undermined the strength of the nation’s current-account surplus and the peso[3].

The wonderful part of this explanation is that this appears to validate my long held tenet that the Philippine government statistics vastly suffers from the “skewedness or specifically the non-representativeness of statistical growth data relative to real economic conditions”[4]

But “smuggling” for me serves as a convenient scapegoat/bogeyman for the peso’s travails.

What is smuggling? Smuggling according to Wikipedia is the illegal transportation of objects or people…in violation of applicable laws or other regulations.

As a side note: in this discussion I will be dealing with smuggling of goods.

The basic reason why smuggling exists is that there is extant demand for goods that has been proscribed or regulated by political authorities. However despite the legal barriers, because of the profit motive to service such demand, entities have worked to circumvent on such mandates via legal or accounting loopholes or bribery or through other avenues.

Put differently, “smuggling” represents the unintended consequence of economic and financial repression that constitutes part of the informal economy[5].

Goods smuggling can be inbound or outbound.

Two examples.

Outbound Smuggling. In 2012, when the BSP raised gold sales tax to 7%—consisting of a 2-percent excise tax and a 5-percent creditable withholding tax, perhaps under the prodding of the IMF[6]—the consequence has been a 90% devastating collapse[7] in the sales of the small scale miners to the legal sole buyer the BSP. The small scale miners, whose production constitutes about 56% of the nation’s gold output have mostly gone underground. The more than doubling of the tax rates has apparently exceeded the tolerance level of small miners and thus has provoked them to use the “tax free” outbound or export route called “smuggling”.

Simplistic expectations to raise revenues by increasing taxes boomeranged. Through economic-financial repression of raising tax rate levels, the Philippine government incentivized small scale mining to shift into smuggling.

This King Canute effect has even been more pronounced in India, where the Indian government has vastly reduced the Indian gold trading in both domestic and the international sphere. The ramification has been to almost entirely divert the gold industry underground. Gold seized from smuggling “multiplied by 14 times between FY ’11 and FY ’14”.[8]

Inbound smuggling. Sin taxes serves as another splendid example of government induced inbound “smuggling”.

In the name of curtailing vices but really to raise revenues for the insatiable spendthrift government, the Philippine government raised taxes on cigarettes and alcohol in 2012. However in contrast to political mainstream’s expectations, the consequence has been the same—the King Canute effect—a collapse in tax revenues and massive substitution in commercial activities through “smuggling”[9].

This King Canute effect of sin taxes has also been the same in the US where higher taxes continues to prompt for unbridled smuggling[10].

The King Canute effect simply reveals that legal edicts, mandates or regulations cannot and will not subvert the fundamental laws of economics.

Generally, inbound “smuggling” adds provision of supply to the economy. This should lower prices and give consumers more choice, which in essence, enhances the consumer’s purchasing power and satisfaction.

Yet the only entities harmed by inbound “smuggling” have been the resource starved extravagant government and their constituents—welfare, warfare, bureaucracy and Pork Barrel based politicians—and their select private sector allies: inefficient companies protected by anti-competition legislations.

And in the name of saving jobs, instituting economic repression via protectionism and financial repression promotes joblessness by restricting investments and thus commercial activities. Ever wonder why despite the so-called “boom”, joblessness remains chronic?

In addition, economic repression protects the financial and economic interests of the entrenched politically connected few. Residents of the Philippines are all consumers—all 96.7 million. Thus, economic repression is tantamount to sacrificing the interests of 90+ million consumers for the benefit of a few tens of thousands. Yet this is what populist politics—social democracy—is made of.

As one would notice, the government creates their self-made “Frankenstein-s”, which ironically they publicly declare are subject for extermination. How? By doing exactly the same things that has engendered their existence.

Nonetheless the so-called proliferation of smuggling activities magnifies on the government statistical inaccuracies.

And importantly, government action to contain smuggling embodies her sustained assault on the informal economy. So how can restraining economic activities via repression extrapolate to economic growth??? Beats me, but this is how popular logic flows.

The Real Score Behind Philippine Peso and Balance of Payment

And why should “smuggling” extrapolate to a weak peso?

The popular argument indicates that “smuggling” enervates the Philippine financial standings via the trade and current account “deficit” channel. This is partly true but hardly provides a sufficient explanation for the rest.

Based on the accounting identity called Balance of Payments (BOP) which “record of all monetary transactions between a country and the rest of the world” the total has to be ZERO

According to Wikipedia.org[11] “When all components of the BOP accounts are included they must sum to zero with no overall surplus or deficit. For example, if a country is importing more than it exports, its trade balance will be in deficit, but the shortfall will have to be counterbalanced in other ways – such as by funds earned from its foreign investments, by running down central bank reserves or by receiving loans from other countries.”

The accounting identity[12]:

BOP = CURRENT ACCOUNT + CAPITAL ACCOUNT = CREDITS - DEBITS= 0

In and of itself, this means that deficits are hardly the cause of a currency’s travails, if they are sufficiently funded.

Deficits become a source of concern when the deficit nation’s funding has been perceived as increasingly becoming inadequate or deficient and or when creditors’ confidence are shaken due to an observed deterioration in the nation’s capacity or the ability or the willingness to pay on her liabilities.

Wikipedia.org describes the balance of payment crisis or a currency crisis[13]:

A BOP crisis, also called a currency crisis, occurs when a nation is unable to pay for essential imports and/or service its debt repayments. Typically, this is accompanied by a rapid decline in the value of the affected nation's currency. Crises are generally preceded by large capital inflows, which are associated at first with rapid economic growth. However a point is reached where overseas investors become concerned about the level of debt their inbound capital is generating, and decide to pull out their funds. The resulting outbound capital flows are associated with a rapid drop in the value of the affected nation's currency.

So the agonizing peso has hardly been about “deficits” per se but rather about the 38.6% M3 growth last January which according to the BSP has been “due to higher demand for credit[14]”.

Yet it has been simply amazing at how the mainstream experts see money and debt as operating in a black hole when discussing exchange rate values.

But this shouldn’t be the case since even celebrity guru Nouriel Roubini, in his lectures in Macroeconomics at the New York Sterns University, has been aware that exchange rates are basically determined by the quantity theory of money as part of the “classical theory of exchange rates” that also includes Purchasing Power Parity.

In the lecture Dr. Roubini cites that a “currency weakens…if we issue more money than the other country”, although the effect is “considerably better over longer periods” than over the short term.[15]

In short even from the mainstream perspective money supply should play a big role in ascertaining of exchange rate ratios.

And as I have long been explaining, it is the demand and supply for a currency unit that determines the exchange rate values. To quote again the late great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises “the valuation of the monetary unit depends not upon the wealth of the country, but upon the ratio between the quantity of money and the demand for it, so that even the richest country may have a bad currency and the poorest country a good one.[16]”

Such demand and supply for a currency unit will thus be ventilated on the conditions of Balance of Payment. How? Through profit margins as determined by price levels. Again Professor von Mises[17] (bold mine)

The balance-of-payments theory forgets that the volume of foreign trade is completely dependent upon prices; that neither exportation nor importation can occur if there are no differences in prices to make trade profitable. The theory clings to the superficial aspects of the phenomena it deals with. It cannot be doubted that if we simply look at the daily or hourly fluctuations on the exchanges we shall only be able to discover that the state of the balance of payments at any moment does determine the supply and the demand in the foreign-exchange market. But this is a mere beginning of a proper investigation into the determinants of the rate of exchange. The next question is, What determines the state of the balance of payments at any moment? And there is no other possible answer to this than that it is the price level and the purchases and sales induced by the price margins that determine the balance of payments. Foreign commodities can be imported, at a time when the rate of exchange is rising, only if they are able to find purchasers despite their high prices.

Changes in the quantity of money have been intertwined with changes in relative price levels of goods and services in the economy that gets to be reflected on both Balance of Payment and currency values.

In the Philippine context, the twin siblings of credit financed asset bubbles and price inflation have been working their way towards reconfiguring the Balance of Payment (BOP) standings.

Relative price inflation pressures, which have been indicative of a maturing credit fuelled property bubble, have begun to manifest itself via government statistics. Rising inflation has now percolated into the bond and currency markets via market prices, in particular higher yield and the declining peso. Despite last week’s improvements, mostly from BSP interventions, the bond and especially the peso remain far from its original ‘easy money’ disposition. Economic logic tells us that such rally cannot be sustained overtime.

As a side note, part of the rally by the peso this week has been due to the "risk ON" regional influences.

And as pointed out last week, Philippine trade balance has been worsening during the current inflationary boom. This means that the falling peso will function as a secondary force or an aggravating factor to the overheating credit financed property, property related and stock market bubbles. A feedback loop mechanism between domestic inflationary forces with the falling peso has been progressively intensifying.

Inbound smuggling has most likely played a big role in the bridging supply provisions for the bubble sector as well as for the general economy, thus has cushioned price inflation during the nascent boom. But this is about to change too.

The falling peso may serve to naturally reduce inbound smuggling not because of policy enforcement but because of reactions to price changes. Moreover, the government’s publicly declared onslaught against smuggling will add to supply side pressures thus exacerbating domestic inflationary pressures. [As an aside, my barber just increased haircut fees by 25%].

In their latest disclosure to increase reserve requirements the BSP appear to be confirming my stagflationary projection[18]:

At the same time, the Monetary Board noted that the balance of risks to the inflation outlook continues to be skewed to the upside, with potential price pressures emanating from pending petitions for adjustments in utility rates and from the possible increases in food and oil prices.

Think about unintended consequences from the zany collision of policies from the incumbent government: the BSP wants to contain price inflation but the unleashing of spending power from banking credit finance in the face of restricting supply via combating “smuggling” by the executive department will likely mean both of them will be proven wrong or none of the two objectives (containment of inflation and prevention of smuggling) will succeed.

And given the apparent structural shift in the economic framework—specifically from external trade to internal asset bubbles—the falling peso will hardly benefit exporters. That’s because much of the resources have already been committed or sunk into bubble projects that will eventually be exposed as unviable via financial losses. In addition domestic inflation will negate any marginal advantages brought by the “cheaper” peso. And this has been fantastically evident in the peso’s long term trend. Despite the 95++% decline of the peso against the US dollar over 55 years, financial and economic repression have hardly brought about advantages to external trade.

Worse, should a real tightening occur, exporters will likely be affected by credit rationing. And the tanking peso will likely upset importers where much of them have also been tied to providing supplies to the bubble sector as explained last week.

Additionally, the greater demand for credit, which again will be reflected on money supply growth, will also be vented on interest rates and on the peso.

So this means that for as long as the BSP permits the inflation of credit fueled asset bubbles, surging price levels compounded by deteriorating or massive expansion of debt conditions will persist to manifest on a corrosion of the much vaunted external conditions of the Philippine economy that will be expressed on interest rates and on the peso.

Stock exchange participants will be the last to know.

A very clear example of this price level-BOP change can be seen via foreign exchange reserves. Again as I pointed out last week, concomitant to the surge in the USD-peso to August 2010 levels late January, the Philippines’ forex reserves tumbled by 5.7% also in January. [note: Philippine forex reserves gained 1.8% in February]

The implication is that the BSP has opted to forego the use of the interest rate channel and instead elected to defend the peso by intervening in the currency markets with the use of the surplus US dollars to buy up the peso. The Philippine government has been so deeply addicted to the stimulus provided by negative real rates (financial repression) such that the BSP can hardly backtrack from implementing bubble blowing policies. Thus the use of reserve requirements rather than the interest rate policy.

Aside from the raising the reserve requirements ratio, given the wild intraday movements of the peso during the week, I deeply suspect that the BSP may have used anew forex reserves to defend the peso. We will see the March data in about two months.

While “smuggling” may have inconsequentially contributed to the pesos’ predicament, the ultimate driver has been the relative money supply growth brought about by a runaway credit bubble that has been influencing price level changes in the economy, the currency and the BOP profile.

Such dynamics is something the mainstream seems to have lost touch with.

Philippine Bonds Dissatisfied with BSP’s Actions

Early last week even foreign media has noticed that as the peso plummeted, hikes in the yield curves in Philippine bonds have expressed alleged “speculations on interest rate tightening”[19].

The weekly rally in the 10 year domestic bonds came first with an initial loss where the 10 year yield spiked to 4.625% before backing off to 4.471%.

Yields of 20 year bonds also expanded to 5.584% before retracing to 5.519% at the week’s close. Although 20 year yields have remained up compared to last week’s close at 5.472%. The same story can be told of the 5 year treasuries where yields charged to 3.862% before withdrawing to 3.748%. From last Friday’s 3.606%, this Friday’s yield decline has not been enough to expunge on the earlier losses.

The interesting picture comes with the short term treasuries. Yields of the 6-month, 1 year and specially the 2 year treasuries have been pushed significantly higher and stayed up until the week’s close.

The BSP actions have hardly influenced the elevated yields of 6 month and 1 year treasuries (now nearly at July 2013 highs) and has instead spiked yields of 2 year treasuries driving the latter’s yields back nearly to January highs.

Given that short term yields have increased faster than the longer end, Philippine yield curve seems as materially flattening.

Higher yields on the short end are symptoms of liquidity strains. While this may be temporary it surely represents signs of ongoing dislocations.

Yet a flattening of the slope as I wrote in April 2013[20] will theoretically reduce the banking system’s net interest margins. Although today’s banking system has been more sophisticated since they don’t rely on net interest income alone…the banking system will have to rely on non-loan markets, otherwise there will be pressure on profits.

So while the peso rallied in the back of BSP’s actions, we seem to be seeing growing signs of fractures in the Philippine treasury market which ironically has been tightly controlled by the banking system and the government.

Who among the banks-financial institutions have been feeling the heat?

Media Cheers as the BSP Tweaks Reserve Ratio

Aside from the other week’s steep plunge of the peso and this week’s seizures in the domestic treasury markets, the BSP previously issued reports covering domestic liquidity and banking loan of the previous month during the end of each month, see the links to the BSP archives of February and January. So I expect the same reports by next week.

Could it be that the Philippine currency and the Philippine treasury markets have both been anticipating another 30++% M3 growth??? Has the BSP’s response also been in reaction to the coming report?

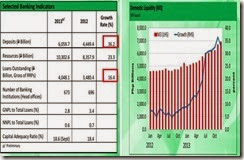

Regardless, the BSP’s move to raise the reserve requirement ratio from 18 to 19% of deposits effective April 4, 2014 represents a symbolic drop in the bucket.

This only means a 5% decrease in the banking system’s potential to expand credit creation. In 2013 banking loans grew by 16.4% or a total of Php 567.7 billion. Should 2014 experience the same nominal rate of growth then this would only mean a reduction of a mere Php 28 billion pesos.

Nonetheless given that the announced capex by real estate and real estate related sectors at conservatively Php 250 billion where most of these will be financed by loans (although reportedly favoring the bond markets), if financed by banking system this will easily surpass the 2013 threshold.

The above diagrams from the BSP’s 2013 annual report[21] represent a stunning picture of the fractional reserve banking at work. Deposits in the Philippine banking system zoomed by a whopping 36% year on year! Deposit growth has practically mirrored the growth in money supply (right).

In the world of fractional banking system, banks issue loans (money from thin air), borrowers spend the money on goods and services while sellers of goods and services deposit sales proceeds to the banking system. Meanwhile reserve requirements are banking mandates to service depositor withdrawals.

As the Mises Institutes wiki explains[22]

The practice of fractional reserve banking expands credit and therefore also expands the money supply (demand deposits and cash) beyond what it would otherwise be in a stable money system. Due to the prevalence of fractional reserve banking, the broad money supply (deposits created via the issuance of loans plus cash) is a much larger multiple than the amount of "real" paper currency created by the country's central bank. That multiple (called the money multiplier) is determined by the reserve requirement or other financial ratio requirements imposed by financial regulators, and by the excess reserves kept by commercial banks.

If we apply this say in the US where reserve rate is at 10% (or 1/10%), and say $10,000,000 in new reserves, the maximum amount of credit expansion from $10m in new reserves is $100 million[23]

Back to the BSP, the new deposit requirement (based on December 2013 deposits of Php 6,059.7 billion) at Php 1.151 trillion already reflects 19% of the BSP’s January’s M3 data. Special Deposit Accounts (SDA) fell by 16.6% over the same period or Php 273 billion had been reverted back to the banking system deposits. Yet it is unclear to me how deposit growth of a staggering Php 1.610 trillion or signifying 2.25x the banking system’s general loan growth has been accomplished.

I suspect that part of such deposit growth may have emanated from offshore banking foreign currency based borrowing that had been converted into pesos which had been spent and deposited into the domestic banking system.

Yet the marginal tweaking by the BSP seems have been seen as unsatisfactory by the domestic bond markets. Ironically some in the mainstream have read this as “tightening” while other experts even alleged that this would be a guide to lower inflation. M3 growth at 30+++ leads to lower inflation??? Water flows uphill now?

Nonetheless, the BSP’s use of the reserve requirements rather than the interest rate policy appears to validate my claim last week that the “BSP has been BOXED into a corner”.

Since the Philippine government has become so deeply addicted to the free lunch provided by monetary steroids or to invisible subsidies in favor of the government and government pet bubble industries that has been charged at the expense of the lowly currency holder, thus the BSP will kick real tightening down the road.

This week’s superficial actions by the BSP in response to the domestic bond and currency market turmoil appear to be a showcase of such pretend-and-extend policies, and thus the variable market responses.

Yet it seems that ultimately it would take a violent market upheaval to force the hands of the BSP.

What will be the outcome of the conflicting policies between the executive branch and the BSP? How much more market turbulence can the BSP afford to pacify? At what costs?

Convulsing Philippine peso and treasury markets have hardly been signs of the return of a bullish ‘easy money’ backdrop. To the contrary these are indications of tightening conditions. Most importantly, they serve as the proverbial writing on the wall.

Assailing the Informal Economy: The Philippines Bans Coin Savings

There are two metrics to gauge whether a nation is on path to attain real economic growth. One is economic freedom (pillared by personal choice, voluntary exchange coordinated by markets, freedom to enter and compete in markets, and protection of persons and their property from aggression by others[24]).

The other is sound money policies[25] founded in “the market's choice of a commonly used medium of exchange” and is “negative in obstructing the government's propensity to meddle with the currency system”.

It is bad enough for a government to penalize their constituents by indirectly promoting transfers of resources to political agents and their favored allies via inflationism or bubble blowing policies. But it is even worse when political forces mount a direct assault on people’s savings and property rights.

Reports say that House Bill 1662 the criminalization of coin hoarding was recently passed in the House panel. The bill supposedly aims[26] to “discouraging private hoarding of coins and by encouraging the people to deposit their money in banking institutions”. It also aims to “re-circulate the hoarded Philippine legal tender coins collected and kept by syndicates currently hoarding coins with impunity that are smelted and converted into another materials of various industrial uses”

First the government monopolizes the money issuance, then restricts the people’s choice of the medium to save. Worse, a mistake in the choice of savings may lead to incarceration and heavy fines. One’s money and savings are now subject to outright confiscation, if not harassment via repressive legislations that openly promotes the interests of the banking industry.

Remember there are only 2 out of 10 households who have access to the banking system, this means many in the informal economy save by virtue of accumulation of coins and in paper money. So essentially this coin hoarding bill signifies as a direct assault on the informal economy. This will also be an attack on the innocent.

Instead of democratizing economic opportunities to encourage the informal sector to grow and assimilate into the formal economy, the incumbent government has been waging war at almost all fronts against the informal economy who mostly represent the middle class or the underprivileged.

First of all coin shortages are often symptoms of inflationism as expressed via the Gresham’s law[27]—“When a government overvalues one type of money and undervalues another, the undervalued money will leave the country or disappear from circulation into hoards, while the overvalued money will flood into circulation”

Recent accounts of coin shortages have been seen in Sri Lanka (2007 and 2014) and in Argentina where 524 million coins issued in 2008 simply vanished[28].

In Zimbabwe, people who saved in coins survived former governor of Zimbabwe’s central bank Gideon Gono’s hideous hyperinflation which peaked at 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000% in November 2008.

From the Wikipedia.org[29] (bold mine)

All old coins dating from the first dollar were reintroduced at face value to the third dollar in Aug 2008, effectively increasing their value 10 trillion-fold, and new $10 and $25 coins were introduced.

And recent accounts of coin shortages in Zimbabwe appears to have been eased by market based mobile banking system[30]

As I pointed out far back in May 2012[31], the Philippine government finally admits that “intrinsic value of the coin is greater than its nominal value especially for the lower-denominated coins” which means the government has been inflating the purchasing power of the local currency, the paper Peso, away.

So by prohibiting or restricting coin savings, the Philippine government essentially limits individual protection from government’s destruction of the currency.

Next coin shortages have been an age old problem.

In medieval Europe when metal prices were lower than the face value of the coins, people would bring the metal to the mint. However when prices of the metals rise beyond the face value of the coin, people will melt the coins (or export or hoard them) as the cheapest way of obtaining the metal, according to a book by Thomas J. Sargent and Francois R. Velde as reviewed by Leland B Yeager[32]

So this merely repeats the errors of the past.

But who is really responsible for the coin shortages? Well it has been no more than the government.

Writes Professor George Selgin[33]

Coin shortages are nothing new. A few months before running out of gold Eagles, the US Mint had to ration silver Eagles. Not long before that, pennies were in very short supply. Nor are other government mints any better. Back in 2007, for instance, Argentina had such a severe change shortage that its panhandlers nearly starved to death, while in southern China, 100-yuan coins commanded a whopping 25 percent premium.

Why are coin shortages so common? Governments typically blame unexpected changes in demand. But suppliers of all sorts of other goods manage to avoid running out, despite even more dramatic demand changes. So what's special about coins? An old chestnut says that if the government were put in charge of the desert, pretty soon there'd be a sand shortage. Recall the plight of consumers under socialism: socialist governments tried to make everything and eventually ran out of everything.

Now socialism is dead, but not when it comes to coining. So coin shortages keep breaking out, as they have ever since governments first monopolized coin making in ancient times.

It seems as the Philippine government has been passing their culpability to the private sector. And in doing so appear to be using such repressive edicts to harass and subjugate on the individual’s property rights. Also notice that inflationism have always been a part of the grand scheme of manifold interventions imposed on society—price and wage controls, capital and currency controls and social mobility or travel restrictions.

The seeming all out blitzkrieg by the government against the informal sector appear as signs that we may be headed in the direction of the Argentina. Add to this the 30% money supply growth. Such repression will become more evident when the bubble economy pops that will send fiscal deficits to the moon.

Yet I hope the current political trend reverses.

If saving via coins has been constrained then foreign currency alternatives will likely be considered by the marketplace. This implies more pressure on the peso. As caveat foreign currencies are still paper money which are subject to relative inflationism.

Rotation or Risk ON or Bull Trap???

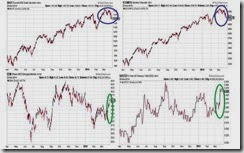

A final thought. Some say that the recent outperformance of Emerging Markets stocks (EEM—lower left window) relative to the US means a rotation and a return to the bullish backdrop.

I doubt such a premise. Using Philippine valuations (PER 30-60 for major blue chips) and signs of emerging price inflation will hardly be bullish for Philippine stocks.

In addition the weakness in the US markets has so far been led by biotechnology sector (not in charts), the Nasdaq (COMPQ—upper right) and the severely overvalued Russell 2000 (RUT—upper left) may be either a temporary reprieve or a periphery to core dynamic.

Yet even as longer end yields for US Treasuries have recently declined. Yields of 2 year USTs (UST2Y—lower right) have sharply risen.

Hardly a good news for a debt financed stock market boom.

[18] BSP loc cit March 27, 2014