The fact is, the programs labeled as being “for the poor,” or “for the needy,” almost always have effects exactly the opposite of those which their well-intentioned sponsors intend them to have.Let me give you a very simple example – take the minimum wage law. Its well-meaning sponsors there are always in these cases two groups of sponsors – there are the well-meaning sponsors and there are the special interests, who are using the well-meaning sponsors as front men. You almost always when you have bad programs have an unholy coalition of the do-gooders on the one hand, and the special interest on the other. The minimum wage law is as clear a case as you could want. The special interests are of course the trade unions – the monopolistic trade craft unions. The do-gooders believe that by passing a law saying that nobody shall get less than $9 per hour (adjusted for today) or whatever the minimum wage is, you are helping poor people who need the money. You are doing nothing of the kind. What you are doing is to assure, that people whose skills, are not sufficient to justify that kind of a wage will be unemployed.The minimum wage law is most properly described as a law saying that employers must discriminate against people who have low skills. That’s what the law says. The law says that here’s a man who has a skill that would justify a wage of $5 or $6 per hour (adjusted for today), but you may not employ him, it’s illegal, because if you employ him you must pay him $9 per hour. So what’s the result? To employ him at $9 per hour is to engage in charity. There’s nothing wrong with charity. But most employers are not in the position to engage in that kind of charity. Thus, the consequences of minimum wage laws have been almost wholly bad. We have increased unemployment and increased poverty.Moreover, the effects have been concentrated on the groups that the do-gooders would most like to help. The people who have been hurt most by the minimum wage laws are the blacks. I have often said that the most anti-black law on the books of this land is the minimum wage law.There is absolutely no positive objective achieved by the minimum wage law. Its real purpose is to reduce competition for the trade unions and make it easier for them to maintain the higher wages of their privileged members.

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups—Henry Hazlitt

Thursday, February 14, 2013

Video: Milton Friedman on the Minimum Wage Law

Quote of the Day: Why Is Obama Such A Cheapskate?

Pres. Obama's proposal to raise the minimum wage to $9.00 per hour, reflects his contempt for lower-income people. If a $9.00 minimum wage would help poorer people - and without any negative effects, as defenders of this form of price-fixing often pretend - why would he not have the state confer untold wealth on us all by raising the minimum wage to $9.00 per minute, or even higher? Why is he such a piker? After all, wealth is just money, is it not? And if providing every American with $100 billion in cash would make us all rich, why is he holding back? If the government of Zimbabwe had the foresight - and generous intentions - to do this, why not America?

Saturday, January 26, 2013

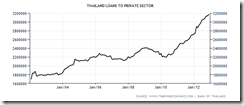

Thailand’s Credit Bubble

Daily minimum wages have risen as much as 89 percent after two increases in the past year. Most factories are located in an area where wages rose to 300 baht per day last April, an average increase of 38 percent, according to the industry ministry.

Another legacy of the 1997 crisis is a lack of investment due to concerns over the country’s debt levels, which has led to persistent current-account surpluses, Kittiratt said. Thailand has had a current-account deficit only once since 1997, according to data compiled by Bloomberg…Over the long term, the government plans to invest in infrastructure to increase imports and reduce pressure on the currency, Kittiratt said. He has proposed spending 2 trillion baht ($67 billion) over seven and a half years on projects such as a railroad network to accelerate investments and put the current account into a deficit.

The Bank of Thailand is keeping a close watch for any indication of a pending collapse in the housing bubble after prices of housing estate units recently sharply increased, Mathee Supapong, a senior director at BoT, said on Friday.Housing loans provided by financial institutions were also substantially up and this was a case to concern, said Mr Mathee.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Example of How the Minimum Wage Hurt Businesses

In November, Albuquerque voters said yes to raising the city's minimum wage from $7.50 to $8.50 an hour, and just 13 days into the increase, historic city restaurant is already feeling the pinch.Owners of the historic El Charritos restaurant on Central say the hike is taking a bit out of business…Romero says the hike came at the worst possible time for the business with an already sluggish economy, as people cut back on eating out and venders upped their prices for food and fuel.To stay afloat El Charritos is cutting back too. They have slashed hours now closing at 2 p.m. on Mondays and Tuesdays to cut back on operating costs. El Charritos has also chosen not to fill six positions and say things could get worse.

In truth, there is only one way to regard a minimum-wage law: it is compulsory unemployment, period. The law says, it is illegal, and therefore criminal, for anyone to hire anyone else below the level of X dollars an hour. This means, plainly and simply, that a large number of free and voluntary wage contracts are now outlawed and hence that there will be a large amount of unemployment.

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Video: Milton Friedman: Minimum Wage Causes Unemployment and Poverty

Friday, May 25, 2012

Germany’s Competitive Advantage over Spain: Freer Labor Markets

When politics is involved, common sense is eschewed.

The vicious propaganda against “austerity” aims to paint the government as the only solution to the crisis, where the so-called “growth” can only be attained through additional government spending funded by more debt. Unfortunately, these politically confused people have forgotten that today’s crisis has been caused by the same factors which they have been prescribing: debt. In short, their answer to the problem of debt is to acquire more debt.

The same with clamors for crisis plagued nations to “exit” the Eurozone in order to devalue the currency. Inflating away standards of living, it is held, will miraculously solve the social problems caused by too much government interventionism that has led to inordinate debt loads.

Professor John Cochrane of the Chicago School nicely chaffs at statist overtures,

The supposed benefit of euro exit and swift devaluation is the belief that people will be fooled that the 10 Drachmas are not a "cut" like the 5 euros would be. Good luck with that.

Little has been given thought to what’s happening on the ground, particularly achieving genuine competitiveness by allowing entrepreneurs to prosper.

At the Mises Institute, Ms Carolina Carmenes and Professor Howden lucidly explains why Germany has been far more competitive than Spain, specifically in the labor markets .

Spain’s labor costs have been cheaper than Germany, yet the Germans get the jobs. Writes Ms. Carmenes and Prof Howden (bold emphasis added)

Spanish employment is now hovering around 23 percent, with over 50 percent of youths jobless. Only around 6 percent of Germans are without work, almost the lowest level in the country since reunification. This divide solidifies Spain's position among the worst-performing economies of the continent, and Germany's vaunted position as among the best.

Yet such a situation might seem paradoxical. One could, for example, look at the wage rates of the respective workers and find that low-cost Spaniards are much more affordable. Profit-maximizing businesses should be expanding their facilities to take advantage of the opportunity the Spanish crisis has provided and eschew higher-cost German labor.

While fixating on nominal labor costs might provide a compelling case for a bright Spanish future, delving into the details provides some darker figures.

Once again the German-Spain comparison shows of the myth of cheap labor

Little thought has also been given to the impact of minimum wage and excessive labor regulations which stifles investment and therefore adds to the pressures of unemployment

Again Ms. Carmenes and Prof Howden (bold emphasis added)

One of the main differences between Germany's and Spain's labor markets is their minimum-wage rates. A Spanish minimum-wage worker can expect to earn about €633 per month. Germany on the other hand enforces no across-the-board minimum wage except in isolated professions — construction workers, roofers, and electricians, as examples.

German employees are free to negotiate their salaries with their employers, without any price-fixing intervention by the government in the form of wage control. (This is not to imply that the German labor market is completely unhampered — jobs are cartelized by industry each with its own wage controls. While this cartelization is not perfect, it does at least recognize that a one-size-fits-all minimum-wage policy is not optimal for the whole country.)

As an example of the German approach to wages, consider the case of a construction worker. In eastern Germany this worker would make a minimum wage of around €9 per hour. His counterpart in western Germany would earn considerably more — almost €11 an hour. This difference allows for productivity differences to be priced separately or local supply-and-demand conditions to influence wages. Working for five days at eight hours a day would yield this German worker anywhere from €360 to €440.

It is obvious that the German weekly wage is almost as high as the monthly Spanish one. What is less obvious is why Germans do not move their facilities to lower-cost Spain.

As the old saying goes, "the more expensive you are to fire, the more expensive you are to hire." If a Spanish company decides to lay off an employee, the severance payment for most labor contracts (a finiquito in Spanish) will amount to 32 days for each year the employee has worked with the company. Although this process is not simple in Germany either, there is no legal severance requirement that companies must pay to redundant workers. The sole requirement is for ample notice to be given, sometimes up to six months in advance. If a Spanish company hires a worker who does not work out as intended, a substantial cost will be incurred in the future to offload the employee. Employers know this, and when hiring workers they exercise caution accordingly, lest this unfortunate and unplanned-for future materialize.

These factors make the perceived or expected cost of labor at times higher in Spain than in Germany, despite the actual monetary cost being lower in euro terms. This effect has been especially pronounced since the adoption of the common currency over a decade ago. As we can see below, the average cost of German labor is largely unmoved since 2000, while Spanish labor has increased about 25 percent over the same period.

When hiring a worker, the nominal wage is only half the story. The employer also needs to know how productive that worker will be. Even after we factor for the extra costs on Spanish labor, a German worker could be more costly. A firm would still choose to hire that worker if his or her productivity was greater.

As we can see in the two figures below, over the last decade a large divergence has emerged between the two countries. While German productivity has more or less kept pace with its small increases in wage rates, the Spanish story is remarkably different. Productivity has lagged, meaning that on a real basis Spanish laborers are much more costly today than they were just 10 years ago.

Of course, boom bust policies have also contributed to such imbalances. The EU integration which had the ECB inflating the system essentially pushed Spanish wages levels up substantially, thereby overvaluing Spanish labor relative to productivity and relative to the Germans and to other European nations…

In his book The Tragedy of the Euro, Philipp Bagus mentions a similar phenomenon. Bagus points to the combination of (1) the rising labor costs that result from eurozone inflation and (2) divergent productivity rates between the countries as a source of imbalance. Indeed, inflation has been one driver of rising (and destabilizing) wages in the periphery of Europe, and especially in Spain. Others include, as we have noted here, minimum wages, regulatory burdens, and severance packages that increase the potential cost of labor.

In either case the effect is the same: wage rates do not necessarily reflect the labor itself, but rather the regulation surrounding it. In Spain, this translates to noncompetitive wages. It is important to remember, though, that this does not imply that the labor itself is necessarily uncompetitive — it is price dependent after all.

Every good has its price, even labor. When prices are hindered from fluctuating to clear markets, imbalances occur. In labor markets those imbalances are unemployed people. Policies such as a one-size-fits-all minimum wage and high mandated severance packages keep the price of Spanish labor above what it needs to be to clear the market.

Until something is done to ease these policies, Spanish labor will remain uncompetitively priced. Until Spanish labor costs can be repriced competitively, Spain's masses will need to endure stifling levels of unemployment.

The only solution to the current crisis is to allow economic freedom to prevail. Of course, this means less power for the politicians and their allies which is why they won't resort to this. Their remedies will naturally be worst than the disease.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Reductio Ad Absurdum on Wage Disparities, Supply of Labor and Exports

In trying to demonstrate the importance of the distinction between causation and correlation, my favorite marketing guru Seth Godin asks “Does a ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader, or do successful bond traders go skiing in Aspen?”

This applies to political economic analysis as well.

Mainstream analysis, particularly those of the rigid Keynesian persuasion, would take the former - ski trip to Aspen make you a successful bond trader-over the latter as the answer or correlation mistaken as causation.

Applied to the political economic sphere they would argue that in order to preserve employment at home, the policy prescription should be a mercantilistic one: inflate (currency devaluation) or impose protectionism (limiting trade via tariffs). Never mind if this flawed argument has been a discredited idea even by 18th century economists. For Keynesian mercantilists, subtraction and not addition equals prosperity (gains).

Their assumption, which mostly signifies from a reductionist perspective, oversimplifies trade as operating in fixed pie wherein one gains at the expense of the other (zero sum).

And this is supported by their rationalization which sees every economic variable as homogenous.

And through selective statistical aggregates, they derive the conclusion that only government, equipped by the knowledge on how to adjust the knobs, can rightly balance out the interest of the nation. [Applied to Seth Godin’s riddle, government should send everyone to Aspen to make them all successful bond traders!]

And also from such perspective they see employment as the only driver of businesses and of economies-forget profits, capital, productivity, property rights, market accessibility and everything else-in the rigid Keynesian world, what only counts are labor costs.

In other words, labor cost, not profits, determines investments which subsequently translate to employment. Thus for them government policies must be directed towards accomplishing this end.

It has further been alleged that the supply of labor accounts for as a vital part in determining wage levels.

The reductionism: large supply of labor equates to low wages and consequently export power.

Let’s see how true this is applied to the real world.

Since labor basically is manpower then population levels would account for as the critical denominator.

One might argue that demographic distribution per nation would be different, which is true, but the difference does not neglect the fact that population levels fundamentally determine the supply of available labor.

Here is the world’s largest population, according to Wikipedia.org,

Given the reductionism which postulates that large labor force equates to low wages, then we should expect these countries, including the US and Japan to have the lowest wage rates in the world!

Yet even without looking at wage statistics we know this to be patently false (as seen from the bigger picture)!

Since wage levels are different per nation or per locality, perhaps the best way to gauge wages would be to use minimum wages as a yardstick.

Minimum wage account for as the national mandated minimum pay levels that are directed towards the lowest skilled workers.

Going back to the mercantilist postulate, since the largest population (largest pool of available labor) per continent belongs to Asia,...

...then the mercantilist logic implies that the lowest wages should be in Asia. Chart courtesy of Geo Hive (xist.org).

Yet according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), based on median minimum wages per country (US $PPP) the lowest wages would be in South East Europe and the CIS!

Asian wages are even higher than Africa and Southeast Europe and the CIS. Another disconnect!!

In addition, if broken down on a per country basis, based on the level of minimum wages in 2007 (PPP US$).... (again from ILO)

We would find that NONE of the largest or most populous countries (all in red arrows) are at the lowest echelon, except for Bangladesh and the Russian Federation seen at the lowest decile. (Yet the latter two are NOT export giants)

In pecking order, China, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria Pakistan and India are mostly situated at the upper segment of the lower half of the graph.

Meanwhile the Philippines can be seen on the higher second quartile, and the US having the highest minimum wages (among the highest populated nations), along with European countries.

So what this proves?

There is hardly any correlation between population levels (supply of labor) and wage levels! The assertion that supply of labor equals low wages is outrageously naive and inaccurate!

And let us further examine how these minimum wage levels impact exports. The following chart of the world’s largest exporters is from Wikipedia.org

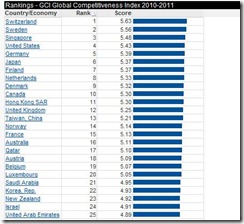

And I would also include global competitiveness as measured by the World Economic Forum (Global Competitiveness report)

So what do we see?

We see a strong correlation between the world’s biggest exporters and the most competitive nations. And one might add to that HIGH minimum wages!

While it would be tempting to argue that high minimum wages equals strong competitiveness/exports, we would be falling for the same post hoc argument trap of misreading correlation as causation like those employed by rigid Keynesians.

The real answer to such wage disparity is the high standards of living in developed economies which arises from the greater capital stock (or productive assets in the economy) and a higher productivity of the citizenry.

As Professor Donald J. Boudreaux explains, (bold highlights mine, emphasize his)

Low-wage labor is generally not low-cost labor. The reason is that the productivity of low-wage workers in China and other developing countries is much lower than is the productivity of workers in America. While low-wage foreigners outcompete high-wage Americans at many low-skill, routine, and repetitive tasks, high-wage Americans can (and do) outcompete low-wage foreigners in those tasks that can be performed efficiently only in advanced economies that are full of the machinery and intricate infrastructure – physical, legal, and cultural – that raise wages by raising worker productivity

In short, high American wages aren’t a disadvantage; they are a happy reflection of the fact the typical American worker is a powerhouse of production.

In short to argue from a wrong premise would mean wrong conclusions.

Why?

Because for politically blinded people, their intuitive tendency is to selectively pick on events or data points (data mining, e.g. low value low skill industries, China) and deliberately misinterpret them (to create a strawman-China's low wages stealing American and Filipino jobs) in order to fit all these into their desired conclusions (cart before the horse reasoning-erect trade barriers).

They similarly deploy false generalizations based on the perceived defects interpreted as a general condition (fallacy of composition-low wages equals export strength).

These represent not only as sloppy ‘blind spot’ thinking but likewise, a reductio ad absurdum or a conclusion based on the reduction to absurdity.

Caveat emptor.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Gender Inequality In Post Graduate Earnings

According to the Economist (bold highlights mine),

``UNIVERSITY offers more than the chance to indulge in a few years of debauchery. A new report from the OECD, a rich country think-tank, attempts to measure how much more graduates can expect to earn compared with those who seek jobs without having a degree. In America the lifetime gross earnings of male graduates are, on average, nearly $370,000 higher than those of non-graduates, comfortably repaying the pricey investment in a university education (female graduates earn an extra $229,000). In South Korea and Spain female graduates pull in a lot more than their male counterparts. In Turkey, although the additional wages are more modest, the difference between men and women is far less pronounced."

OECD in a press release makes additional notes where male ROI (on earning/learning) have been higher in most instances... (emphasis added) [note I haven't accessed the complete report]

``The average net public return across OECD countries from providing a male student with a university education, after factoring in all the direct and indirect costs, is almost USD 52,000, nearly twice the average amount of money originally invested.

``For female students, the average net public return is lower because of their lower subsequent earnings. But overall the figures provide a powerful incentive to expand higher education in most countries through both public and private financing...

I would comment that much of this outlook is more a function of the financial perspective and omits social aspects (role of maternal or child bearing women on lower wages) based on the press release.

The OECD adds, (again all emphasis mine)

``Among other points, the 2009 edition of Education at a Glance reveals that:

``The number of people with university degrees or other tertiary qualifications has risen on average in OECD countries by 4.5% each year between 1998 and 2006. In Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey, the increase has been 7% per year or more

``In 2007, one in three people in OECD countries aged between 25 and 34 had a tertiary level qualification. In Canada, Japan and Korea, the ratio was one in two.

``In most countries, the number of people who leave school at the minimum leaving age is falling, but in Germany, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Turkey and the United States their numbers continue to rise.

``Early childhood education is growing fast, and nowhere more than in Sweden. On average in OECD countries, enrolments have risen from 40% of 3-4 year-olds in 1998 to 71% in 2007; and in Turkey, Mexico, Korea, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and Germany enrolment in early childhood education more than doubled.

``Young people who leave school at the minimum leaving age without a job are likely to spend a long time out of work. In most countries over half of low-qualified unemployed 25-34 year-olds are long-term unemployed.

``People who complete a high-school education tend to enjoy better health than those who quit at the minimum leaving age. And people with university degrees are more interested in politics and more trusting of other people."

Well, the OECD seem to omit the impact of minimum wages in the role of unskilled and school drop-out unemployment figures.

The outlook appears skewed towards promoting government spending in education.