At the Wall Street Journal, American Enterprise Institute’s Peter J. Wallison explains how capital regulations are partly responsible for the current mess (bold emphasis mine)

Basel is the Swiss city where the world's bank supervisors regularly meet to consider and establish these rules. Among other things, the rules define how capital should be calculated and how much capital internationally active banks are required to hold.

First decreed in 1988 and refined several times since then, the Basel rules require commercial banks to hold a specified amount of capital against certain kinds of assets. Under a voluntary agreement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the largest U.S investment banks were also subject to the form of Basel capital rules that existed in 2008. Under these rules, banks and investment banks were required to hold 8% capital against corporate loans, 4% against mortgages and 1.6% against mortgage-backed securities. Capital is primarily equity, like common shares.

Although these rules are intended to match capital requirements with the risk associated with each of these asset types, the match is very rough. Thus, financial institutions subject to the rules had substantially lower capital requirements for holding mortgage-backed securities than for holding corporate debt, even though we now know that the risks of MBS were greater, in some cases, than loans to companies. In other words, the U.S. financial crisis was made substantially worse because banks and other financial institutions were encouraged by the Basel rules to hold the very assets—mortgage-backed securities—that collapsed in value when the U.S. housing bubble deflated in 2007.

Today's European crisis illustrates the problem even more dramatically. Under the Basel rules, sovereign debt—even the debt of countries with weak economies such as Greece and Italy—is accorded a zero risk-weight. Holding sovereign debt provides banks with interest-earning investments that do not require them to raise any additional capital.

Accordingly, when banks in Europe and elsewhere were pressured by supervisors to raise their capital positions, many chose to sell other assets and increase their commitments to sovereign debt, especially the debt of weak governments offering high yields. If one of those countries should now default, a common shock like what happened in the U.S. in 2008 could well follow. But this time the European banks will be the ones most affected.

In the U.S. and Europe, governments and bank supervisors are reluctant to acknowledge that their political decisions—such as mandating a zero risk-weight for all sovereign debt, or favoring mortgages and mortgage-backed securities over corporate debt—have created the conditions for common shocks.

I have explained here and here how Basel capital standard regulations does not address the root of the crisis—fiat money and central banking—and will continue to churn out rules premised on political goals, knee jerk responses to current predicaments (time inconsistent rules) and incomplete knowledge.

A manifestation of the institutional distortions as consequence to regulations which advances political goals can be noted at the last paragraph where US and European governments and bank supervisors are “reluctant to acknowledge that their political decisions”, which have not only “created conditions for common shocks”, but has existed to fund the welfare state and the priorities of political leaders in boosting homeownership ownership which benefited or rewarded the politically privileged banks immensely.

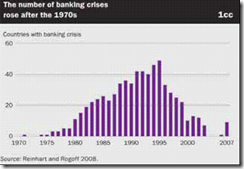

Capital regulation rules will continue to deal with the superficial problems of the banking system which implies that banking crises will continue to haunt us or won’t be going away anytime soon despite all model based capital ratio adjustments. It's been this way since the closing of the gold window or the Nixon shock (see above chart from the World Bank)