For Ben Bernanke and their ilk, the world exists in a causation vacuum, as things are just seen as they are, as if they are simply "given". And people’s action expressed by the marketplace, are seen as fallible, which only requires the steering guidance of the technocracy (the arrogant dogmatic belief that political authorities are far knowledgeable than the public).

Monetary economist Professor George Selgin majestically blasts Ben Bernanke’s self-glorification. (bold emphasis mine)

So like any central banker, and unlike better academic economists, Bernanke consistently portrays inflation, business cycles, financial crises, and asset price "bubbles" as things that happen because...well, the point is that there is generally no "because." These things just happen; central banks, on the other hand, exist to prevent them from happening, or to "mitigate" them once they happen, or perhaps (as in the case of "bubbles") to simply tolerate them, because they can't do any better than that. That central banks' own policies might actually cause inflation, or contribute to the business cycle, or trigger crises, or blow-up asset bubbles--these are possibilities to which every economist worth his or her salt attaches some importance, if not overwhelming importance. But they are also possibilities that every true-blue central banker avoids like so many landmines. Are you old enough to remember that publicity shot of Arthur Burns holding a baseball bat and declaring that he was about to "knock inflation out of the economy"? That was Burns talking, not like a monetary economist, but like the Fed propagandist that he was. Bernanke talks the same way throughout much (though not quite all) of his lecture.

And for the central bank religion, politics has never been an issue. It’s always been about the virtuous state of public service channeled through economic policies…

In describing the historical origins of central banking, for instance, Bernanke makes no mention at all of the fiscal purpose of all of the earliest central banks--that is, of the fact that they were set up, not to combat inflation or crises or cycles but to provide financial relief to their sponsoring governments in return for monopoly privileges. He is thus able to steer clear of the thorny challenge of explaining just how it was that institutions established for function X happened to prove ideally suited for functions Y and Z, even though the latter functions never even entered the minds of the institutions' sponsors or designers!

By ignoring the true origins of early central banks, and of the Bank of England in particular, and simply asserting that the (immaculately conceived) Bank gradually figured-out its "true" purpose, especially by discovering that it could save the British economy now and then by serving as a Lender of Last Resort, Bernanke is able to overlook the important possibility that central banks' monopoly privileges--and their monopoly of paper currency especially--may have been a contributing cause of 19th-century financial instability. How currency monopoly contributed to instability is something I've explained elsewhere. More to the point, it is something that Walter Bagehot was perfectly clear about in his famous 1873 work, Lombard Street. Bernanke, in typical central-bank-apologist fashion, refers to Bagehot's work, but only to recite Bagehot's rules for last-resort lending. He thus allows all those innocent GWU students to suppose (as was surely his intent) that Bagehot considered central banking a jolly good thing. In fact, as anyone who actually reads Bagehot will see, he emphatically considered central banking--or what he called England's "one-reserve system" of banking--a very bad thing, best avoided in favor of a "natural" system, like Scotland's, in which numerous competing banks of issue are each responsible for maintaining their own cash reserves.

People hardly realize that central banks had been born out of politics and survives on taxpayer money which is politics, and eventually will die out of politics.

Any discussion of politics affecting central banking policymaking has to be purposely skirted or evaded.

Policies must be painted as having positive influences or at worst neutral effects. This leaves all flaws attributable to the marketplace.

In reality, any admission to the negative consequence of the central bank polices would extrapolate to self-incrimination for central bankers and the risk of losing their politically endowed privileges.

Besides ignoring the destabilizing effects of central banking--or of any system based on a currency monopoly--Bernanke carefully avoids any mention of the destabilizing effects of other sorts of misguided financial regulation. He thus attributes the greater frequency of banking crises in the post-Civil War U.S. than in England solely to the lack of a central bank in the former country, making one wish that some clever GWU student had interrupted him to observe that Canada and Scotland, despite also lacking central banks, each had far fewer crises than either the U.S. or England. Hearing Bernanke you would never guess that U.S. banks were generally denied the ability to branch, or that state chartered banks were prevented by a prohibitive federal tax from issuing their own notes, or that National banks found it increasingly difficult to issue their own notes owing to the high cost of government securities required (originally for fiscal reasons) as backing for their notes. Certainly you would not realize that economic historians have long recognized (see, for starters, here andhere) how these regulations played a crucial part in pre-Fed U.S. financial instability. No: you would be left to assume that U.S. crises just...happened, or rather, that they happened "because" there was no central bank around to put a stop to them.

Because he entirely overlooks the role played by legal restrictions in destabilizing the pre-1914 U.S. financial system, Bernanke is bound to overlook as well the historically important "asset currency" reform movement that anticipated the post-1907 turn toward a central-bank based monetary reform. Instead of calling for yet more government intervention in the monetary system the earlier movement proposed a number of deregulatory solutions to periodic financial crises, including the repeal of Civil-War era currency-backing requirements and the dismantlement of barriers to nationwide branch banking. Canada's experience suggested that this deregulatory program might have worked very well. Unfortunately concerted opposition to branch banking, by both established "independent" bankers and Wall Street (which gained lots of correspondent business thanks to other banks' inability to have branches there) blocked this avenue of reform. Instead of mentioning any of this, Bernanke refers only to the alternative of relying upon private clearinghouses to handle panics, which he says "just wasn't sufficient." True enough. But the Fed, first of all (as Bernanke himself goes on to admit, and as Friedman and Schwartz argue at length), turned out be be an even less adequate solution than the clearinghouses had been; more importantly, the clearinghouses themselves, far from having been the sole or best alternative to a central bank, were but a poor second-best substitute for needed deregulation.

To be fair, Bernanke does eventually get 'round to offering a theory of crises. The theory is the one according to which a rumor spreads to the effect that some bank or banks may be in trouble, which is supposedly enough to trigger a "contagion" of fear that has everyone scrambling for their dough. Bernanke refers listeners to Frank Capra's movie "It's a Wonderful Life," as though it offered some sort of ground for taking the theory seriously, though admittedly he might have done worse by referring them to Diamond and Dybvig's (1983) even more factitious journal article. Either way, the impression left is one that ought to make any thinking person wonder how any bank ever managed to last for more than a few hours in those awful pre-deposit insurance days. That quite a few banks, and especially ones that could diversify through branching, did considerably better than that is of course a problem for the theory, though one Bernanke never mentions. (Neither, for that matter, do many monetary economists, most of whom seem to judge theories, not according to how well they stand up to the facts, but according to how many papers you can spin off from them.) In particular, he never mentions the fact that Canada had no bank failures at all during the 1930s, despite having had no central bank until 1935, and no deposit insurance until many decades later. Nor does he acknowledge research by George Kaufman, among others, showing that bank run "contagions" have actually been rare even in the relatively fragile U.S. banking system. (Although it resembled a system-wide contagion, the panic of late February 1933 was actually a speculative attack on the dollar spurred on by the fear that Roosevelt was going to devalue it--which of course he eventually did.) And although Bernanke shows a chart depicting high U.S. bank failure rates in the years prior to the Fed's establishment, he cuts it off so that no one can observe how those failure rates increased after 1914. Finally, Bernanke suggests that the Fed, acting in accordance with his theory, only offers last-resort aid to solvent ("Jimmy Stewart") banks, leaving others to fail, whereas in fact the record shows that, after the sorry experience of the Great Depression (when it let poor Jimmy fend for himself), the Fed went on to employ its last resort lending powers, not to rescue solvent banks (which for the most part no longer needed any help from it), but to bail out manifestly insolvent ones. All of these "overlooked" facts suggest that there is something not quite right about the suggestion that bank failure rates are highest when there is neither a central bank nor deposit insurance. But why complicate things? The story is a cinch to teach, and the Diamond-Dybvig model is so..."elegant." Besides, who wants to spoil the plot of "It's a Wonderful Life?"

Cherry picking of reference points and censorship had been applied on historical accounts that does not favor central banking.

Of course, it is natural for central bankers to be averse to the gold standard. A gold standard would reduce or extinguish central banker’s (as well as politicians') political control over money.

Bernanke's discussion of the gold standard is perhaps the low point of a generally poor performance, consisting of little more than the usual catalog of anti-gold clichés: like most critics of the gold standard, Bernanke is evidently so convinced of its rottenness that it has never occurred to him to check whether the standard arguments against it have any merit. Thus he says, referring to an old Friedman essay, that the gold standard wastes resources. He neglects to tell his listeners (1) that for his calculations Friedman assumed 100% gold reserves, instead of the "paper thin" reserves that, according to Bernanke himself, where actually relied upon during the gold standard era; (2) that Friedman subsequently wrote an article on "The Resource Costs of Irredeemable Paper Money" in which he questioned his own, previous assumption that paper money was cheaper than gold; and (3) that the flow of resources to gold mining and processing is mainly a function of gold's relative price, and that that relative price has been higher since 1971 than it was during the classical gold standard era, thanks mainly to the heightened demand for gold as a hedge against fiat-money-based inflation. Indeed, the real price of gold is higher today than it has ever been except for a brief interval during the 1980s. So, Ben: while you chuckle about how silly it would be to embrace a monetary standard that tends to enrich foreign gold miners, perhaps you should consider how no monetary standard has done so more than the one you yourself have been managing!

Bernanke's claim that output was more volatile under the gold standard than it has been in recent decades is equally unsound. True: some old statistics support it; but those have been overturned by Christina Romer's more recent estimates, which show the standard deviation of real GNP since World War II to be only slightly greater than that for the pre-Fed period. (For a detailed and up-to-date comparison of pre-1914 and post-1945 U.S. economic volatility see my, Bill Lastrapes, and Larry White's forthcoming Journal of Macroeconomics paper, "Has the Fed Been a Failure?").

Nor is Bernanke on solid ground in suggesting that the gold standard was harmful because it resulted in gradual deflation for most of the gold-standard era. True, farmers wanted higher prices for their crops, if not general inflation to erode the value of their debts--when haven't they? But generally the deflation of the 19th century did no harm at all, because it was roughly consistent with productivity gains of the era, and so reflected falling unit production costs. As a self-proclaimed fan of Friedman and Schwartz, Bernanke ought to be aware of their own conclusion that the secular deflation he complains about was perfectly benign. Or else he should read Saul's The Myth of the Great the Great Depression, or Atkeson and Kehoe's more recent AER article, or my Less Than Zero. In short, he should inform himself of the fundamental difference between supply-drive and demand-driven deflation, instead of lumping them together, and lecture students accordingly.

Although he admits later in his lecture (in his sole acknowledgement of central bankers' capacity to do harm) that the Federal Reserve was itself to blame for the excessive monetary tightening of the early 1930s, in his discussion of the gold standard Bernanke repeats the canard that the Fed's hands were tied by that standard. The facts show otherwise: Federal Reserve rules required 40% gold backing of outstanding Federal Reserve notes. But the Fed wasn’t constrained by this requirement, which it had statutory authority to suspend at any time for an indefinite period. More importantly, during the first stages of the Great (monetary) Contraction, the Fed had plenty of gold and was actually accumulating more of it. By August 1931, it's gold holdings had risen to $3.5 billion (from $3.1 billion in 1929), which was 81% of its then-outstanding notes, or more than twice its required holdings. And although Fed gold holdings then started to decline, by March 1933, which is to say the very nadir of the monetary contraction, the Fed still held over than $1 billion in excess gold reserves. In short, at no point of the Great Contraction was the Fed prevented from further expanding the monetary base by a lack of required gold cover.

Finally, Bernanke repeats the tired old claim that the gold standard is no good because gold supply shocks will cause the value of money to fluctuate. It is of course easy to show that gold will be inferior on this score to an ideally managed fiat standard. But so what? The question is, how do the price movements under gold compare to those under actual fiat standards? Has Bernanke compared the post-Sutter's Mill inflation to that of, say, the Fed's first five years, or the 1970s? Has he compared the average annual inflation rate during the so-called "price revolution" of the 16th century--a result of massive gold imports from the New-World--to the average U.S. rate during his own tenure as Fed chairman? If he bothered to do so, I dare say he'd clam up about those terrible gold supply shocks.

So when it comes to the gold standard, it is not only the omission of facts and of glaring blind spots, but importantly, it is about deliberate twisting of the facts! At least they practice what they preach--they manipulate the markets too.

Now this is what we call propaganda.

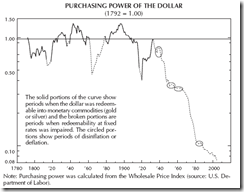

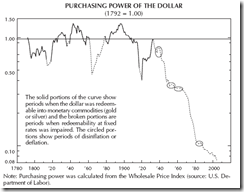

It is best to point out how Bernanke’s central banking has destroyed the purchasing power of the US dollar as shown in the chart above.

Yet here is another example of the mainstream falling for Bernanke’s canard.

Writes analyst David Fuller,

Preservation of purchasing power is the main reason why anyone would favour a gold standard. However, if we assume, hypothetically, that the US and other leading countries moved back on to a gold standard, I do not think many of us would like the deflationary consequences that followed. Also, a gold standard would almost certainly involve the confiscation of private holdings of bullion, as has occurred previously. Most of us would not like to lose our freedom to hold bullion.

I have long argued that we would never see the reintroduction of a gold standard because no leading government is likely to surrender control over its own money supply. For current reasons, just ask the Greeks or citizens of other peripheral Eurozone countries, struggling to cope with no more than a euro standard.

There would also be national security issues as it would not be difficult for rogue states to manipulate the price of bullion as an act of economic war.

First of all, the paper money system is not, and will not be immune to the deflationary impact caused by an inflationary boom. That’s why business cycles exist. Under government’s repeated doping of the marketplace we would either see episodes of monetary deflation (bubble bust) or a destruction of the currency system (hyperinflation) at the extremes.

As Professor Ludwig von Mises wrote

The wavelike movement affecting the economic system, the recurrence of periods of boom which are followed by periods of depression, is the unavoidable outcome of the attempts, repeated again and again, to lower the gross market rate of interest by means of credit expansion. There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

Next, as previously pointed out the intellectuals and political authorities resort to semantic tricks to mislead the public.

Deflation caused by productivity gains (pointed out by Professor Selgin) isn’t bad but rather has positive impacts—as evidenced by the advances of technology.

Rather it is the money pumping and the leverage (gearing), or the erosion of real wealth, caused by prior inflationism from the central bank sponsored banking system. These political actions spawns outsized fluctuations and the adverse ramifications of monetary deflation.

And it is the banking system will be more impacted than that the real economy which is the reason for these massive bailouts and expansion of balance sheets of central banks. It's about political interest than of public interests.

In addition, it is wildly inaccurate to claim to say gold standard would “involve the confiscation of private holdings of bullion”. FDR’s EO 6102 in 1933 came at the end of the gold bullion standard which is different from the classical gold standard. In the classic gold standard, gold (coins) are used as money or the medium of exchange, so confiscation of gold would mean no money in circulation. How logical would this be?

Finally while the assertions that “no leading government is likely to surrender control” seems plausible, this seems predicated on money as a product of governments—which is false. Effects should not be read as causes.

As the great F. A. Hayek wrote (Denationalization of Money p.37-38)

It the superstition that it is necessary for government (usually called the 'state' to make it sound better) to declare what is to be money, as if it had created the money which could not exist without it, probably originated in the naive belief that such a tool as money must have been 'invented' and given to us by some original inventor. This belief has been wholly displaced by our understanding of the spontaneous generation of such undesigned institutions by a process of social evolution of which money has since become the prime paradigm (law, language and morals being the other main instances).

If governments has magically transformed money into inviolable instruments then hyperinflation would have never existed.

At the end of the day, the world in which central bankers and their minions portray seems no less than vicious propaganda.