Domestic media and the mainstream cheers on reports of the vast improvements by the Philippines in the Doing Business rankings by the IFC-World Bank.

The Philippines joins other outperformers led by Ukraine, Rwanda, the Russian Federation, Kosovo, Djibouti, Côte d’Ivoire, Burundi, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and Guatemala

This article from Rappler gives a good account where the gist of the so-called positive developments has been allegedly made.

Regulatory reforms that helped improve the Philippines' ranking were evident in the following 3 criteria:One, the introduction of a fully operational online filing and payment system that made tax compliance easier for companies.The government has aimed to reduce the number of steps to pay taxes to 14 from the previous 47. The survey showed it still takes 36 steps.Two, the simplified occupancy clearances that eased construction permitting:The government wanted to cut the steps to obtaining construction permits to just 12 from 29. The survey results showed it currently takes 25.Three, the new regulations guaranteeing borrowers’ right to access their data in the country’s largest credit bureau.These were some of the areas the government has created specialized teams for to address each of the 10 indicators on the difficulty or ease of doing business in the country that IFC is tracking.The teams' priorities were on indicators that have to do with starting a business, getting credit, protecting investors and resolving insolvency.

Here I will offer a contrarian analysis (using the great Bastiat's Seen and Unseen analytical framework) of the so-called outperformance in Doing Business rankings based on the areas which posted the biggest advancement.

1. Paying Taxes.

It is natural for the Philippine government to prioritize in the enhancements of tax collections.

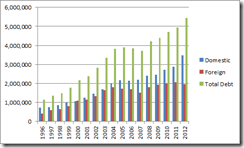

That’s because the government has been spending far more than the revenues the government has generated. Data from NSCB and Bureau of Treasury

Yet the increase in the growth rate of government spending has been accelerating to the upside. On the other hand, revenues while also increasing has failed to keep up with the pace of spending growth.

Moreover, while the rate of government spending appears “linear”, revenues has been subject to fluctuations in the economy

The current “boom” has hardly cut back on the budget deficits that had been accrued during the global 2008 crisis.

In 2010, deficits swelled in the aftermath of a sharp decline in tax revenue collections relative to what seems as steady or constant increase in the trend of government spending. The current deterioration of deficits erased the earlier efforts by the past administration to balance the budget.

In addition, according to the Department of Finance, through July year on year growth of revenues was at 17.3% relative to spending at 21.7%. So nominal deficits (-4.4%) at the current rate will likely even deteriorate more if such a trend persists.

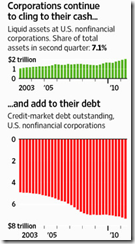

Of course deficit spending unfilled by taxes has been and will be covered by debts. So underneath the surface of a supposed boom has been the swelling of the debt levels.

The government has already been spending a lot more than they can earn, even at pre-Doing Business improvement levels. This means that in contrast to the optimistic perspective, more efficient tax collection will motivate politicians to spend even more. And with bigger government spending, efficient tax collections will extrapolate to higher taxes.

Moreover, money spent for public consumption will mean less money spent for productive activities. Government spending will only add temporarily to statistical growth. In reality, via crowding out of the private sector, government spending diminishes real economic growth. That's because government has no resources to fund any of their spending programs such that the government principally relies on the forcible extraction of savings, output or wealth from the productive agents by taxation. And because government spending cannot be measured by market metrics as they are a monopoly, such spending represent consumption.

So this hardly signifies a positive news over the long term.

2. Construction Permits

In the consensus perspective, ballooning budget deficit and public debt figures when compared to the statistical growth (debt/gdp, deficit/gdp) has been seen as 'stable' or barely viewed as a source of concern.

This is largely because the 'strong' denominator or statistical growth figure (gdp) have “muted” the numerators (debt and deficit).

Such underappreciation of risks has been due to the skewed computation of statistical growth. Yet debts and deficits has largely been driven by the very factors (government spending), aside from the bubbles in the formal economy (nominal private sector debt), constituting statistical growth.

This leads us to the next "big" advance in Doing Business.

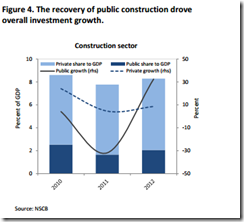

The 2nd quarter 2013 Philippine statistical growth clock came at 7.8%. But when one scrutinizes on the National Statistical Coordination Board data, economic growth emanated from mostly construction and government spending (based on expenditures).

And the construction share of growth includes government spending, where the share of public construction has increasingly added to statistical growth data based on World Bank data

In short, measures to improve regulations in the construction and real estate industry seem as deliberately designed to accommodate a real estate-construction boom in order to boost the statistical economy.

Yet how has the boom in these sectors been funded? Well by credit expansion.

BSP data shows how bank lending to the real estate has exploded since 2010 until 2012

Despite some moderation in the current pace of bank lending, construction and real estate loans remains vastly above “statistical growth”. Of course there has also been the Philippine version of the shadow banking industry.

3. Getting Credit.

The third room for the Doing Business upgrade has been in the partial easing of credit regulations, particularly “guaranteeing borrowers’ right to access their data”

As noted above, the booming areas, specifically real estate and construction and allied industries have mainly been funded by a credit boom

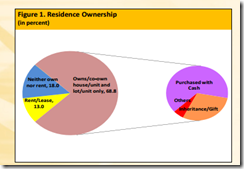

On the consumer side, given that 8 in every 10 households are estimated as unbanked according to the BSP’s annual report…

…and that only 4% of the households have credit cards…

…and where 6.8% of households borrowed money for housing

The above data suggests that “Guaranteeing borrowers’ right to access their data” will hardly be a factor in enticing the informal economy to access the formal banking sector. The average borrower will hardly be concerned about right to access data but rather over access to funds.

True, consumer credit has grown in 2010-2012

…and also through 2013, but they have largely remained below the pace of the supply side growth rate.

Again the so-called “guaranteeing borrowers’ right to access their data” will unlikely boost the overall credit market for the simple reason it does not address the disease: rigid regulations (e.g. AMLA) and taxes that inhibit access to the formal banking system.

Instead “getting credit” will likely buttress the asset speculators, whom have been driving an asset mania, the same entities who have access to the formal banking sector and to the capital markets, as well as, the financiers of these speculative boom.

In short, the credit financed boom has been concentrated to a small sector of the Philippine economy who will benefit from "doing business" upgrade.

Yet in order to maintain current statistical growth levels largely dependent on debt, this means inflating bigger asset bubbles financed by even more ballooning of debt levels. The so-called Doing Business reforms has just facilitated this.

Bottom line: The biggest improvements in the Philippine IFC’s "Doing Business" has hardly been about promoting small and medium scale businesses and or the informal economy

Induced by zero bound rates, the selective easing of regulations essentially compounds on the accommodation by the government of the debt financed speculative binge on asset markets, as well as, debt financed government consumption.

Instead,

ease of paying taxes, construction permits and getting credit only

reinforces the transfer of resources (via inflationism, deficit spending and asset inflation) from society to the political class and their favored allies and constituents

This has been hailed by the short term looking consensus as an ideal growth paradigm.

But as the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises warned,

The popularity of inflation and credit expansion, the ultimate source of the repeated attempts to render people prosperous by credit expansion, and thus the cause of the cyclical fluctuations of business, manifests itself clearly in the customary terminology. The boom is called good business, prosperity, and upswing. Its unavoidable aftermath, the readjustment of conditions to the real data of the market, is called crisis, slump, bad business, depression. People rebel against the insight that the disturbing element is to be seen in the malinvestment and the overconsumption of the boom period and that such an artificially induced boom is doomed. They are looking for the philosophers' stone to make it last.

Yet the soundness of such paradigm may soon be tested by the global bond vigilantes