The race to build real estate projects funded by debt by property developers and by the government has been rapidly inflating domestic property prices.

I was surprised to have read an article[1] citing a Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL) research as saying with unabashed confidence that despite soaring prices and massive supply growth there is no glut in the property sector (bold mine)

A sharp increase in new supply began in 2005. Since then, supply growth has averaged more than 30% annually. The total stock of condominiums jumped from 7,000 at the beginning of the millennium, to around 90,000 units by end of 2011, according to JLL. But Jll sees no glut, and CBRE Philippines’ executive director for global research and consultancy, Victor Asuncion, shares the same viewpoint….

Vacancy rates in Makati rose to 11.7% in Q1 2012 from 9.4% a year earlier, according to Colliers. The rise is attributable to new condominiums adjacent to, but not in, Makati - and in regions near Metro Manila.

This is a prime example of Warren Buffett’s advice of “never ask a barber if you need a haircut”. People will continue to talk up their industry regardless of the risks and of reality.

Common sense tells us that if economic growth stands at 7%, and supply side growth is at 30% annually for the last 8 years, unless the law of economics grind to a halt, eventually there will be a glut.

But the statistical economic growth which the article relies on as demand for burgeoning supplies has exactly been driven by the supply side growth of the property sector.

The article says that a remittance based demand is likely to slow due to factors which they refer to World Bank as -Stricter Implementation of the migrant workers’ bill of rights; -Political uncertainties in host countries; and -The slowdown in the advanced economies. The Pollyannaish article also pins on the growth of BPO industry as potential source of demand.

Yet the rise in vacancy rates in Makati by 11.7% from 9.4% while seemingly statistically small represents a 24.45% increase! And this could be the periphery to the core process.

I have pointed out in the past that the Asian crisis was partly triggered when Thailand’s vacancy rates soared to 15%[2].

The article only confirms my observation of a debt driven property bubble.

Total real estate loans country-wide soared by 42% to PHP546.51 billion (US$12.47 billion) in 2012 from the previous year, based on figures from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), the country’s central bank. Despite the spectacular growth, the size of the mortgage market remains small at about 5.5% of GDP in 2012.

Of course, the mortgage market is small and will likely remain small because of the limited penetration level by the population on the formal banking industry. This isn’t Singapore or Hong Kong. We should see a bigger enrolment of the population on the banking industry first before we can expect the mortgage markets to expand. And the banking industry would have to downscale regulations for more people to enrol.

The property market reflects on the conditions of the stock market.

Figure 8 World Bank Market Cap as % of GDP

The boom in local stocks which in 2012 market capitalization of listed companies according to World Bank accounts for 105.6% of the GDP[3] has only added 22% for a total of 525,850 accounts for the entire PSE brokerages from 2007[4]. This means that booming stocks benefits less than 525,850 accounts (individuals or corporations) or particularly the 83% of market capitalization controlled by a few families whom are now using aggressive leveraging.

The article also notes that “Most houses are sold for cash or pre-sold. Property buyers also face high transaction costs, corruption and red tape, fake land titles and substandard building practices.” The cash transactions are manifestations of clout of the informal economy and the dearth of access to the formal banking sector. And part of the preselling has been financed by developers themselves which the World Bank calls as the domestic shadow banking industry[5].

Finally here is the kicker, from the same article “Recovery from the subsequent crash has been slow. Nominal prices are now back above 1997 levels, but prices are still 46% below pre-Asian crisis peak levels in real terms (Q1 2012) – an astonishing reminder of how much the crash cost.”

Real terms (based on government statistics) don’t seem as an adequate or accurate representation property values.

My neighbourhood store raised the prices of my favorite merienda lumpia by 20% about 2 weeks ago. My daughter’s favorite pie Banoffee recently jumped by 10%. My favorite vendor who maintains his fishball price at 50 cents has shown a considerable shrinkage in the size of his products. I asked why this is so, he says that his supplier can’t raise prices so they deflate the size of their products. Real time economics from the man on the street. Even government’s lotto prices has recently been doubled which accounts for 3.93% lotto inflation. My neighbourhood rental prices have increased by about 10%.

The statistical world is far from the real world. It seems ivory tower economists don’t ever spend at all to know of this reality.

And by the way, a domestic central banker admits that CPI prices don’t accurately reflect on real inflation. At a Bank of International Settlements paper BSP Deputy Governor Diwa C Guinigundo writes[6] (bold mine)

Excluding asset price components from headline inflation also has little effect. Currently, the CPI includes only rent and minor repairs. The rent component of the CPI is, however, not reflective of the market price because of rent control legislation. The absence of a real estate price index (REPI) reflects valuation problems, owing largely to the institutional gaps in property valuation and taxation. While the price deflator derived from the gross value added from ownership of dwellings and real estate could represent real property price, it is also subject to frequent revisions, making it difficult to forecast inflation.

There you have it. The cat is out of the bag. Philippine CPI inflation is NOT a reliable indicator of inflation.

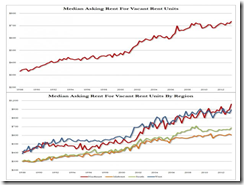

Importantly, real estate nominal prices have reached the 1997 highs.

And lastly I often hear officials say how much a backlog in demand for property in the low end market as a retort against suggestions of bubbles. They have suggested that the shortage of the housing industry is as much as 7 million units[7].

The problem with this concept is that low cost and socialized housing is not a market based demand, but rather a political demand for housing.

The basic assumption is that lack of housing is mainly a pecuniary factor caused by inequality or the lack of social justice. So the government undertakes programs to expand homeownership via socialized or subsidized housing.

So for instance when the BSP claims that 68% of households owns or co-owns their houses[8], this leaves 32% of households who don’t own their homes. This includes me.

So from the government perspective this represents “demand”. Since there are 20.2 million household according to Bureau of Census estimates as of 2010[9], 32% equals 6.4 million!

But homeownership has not just been a function of income. It is also a choice. I personally know of a family who rents their residence at a posh exclusive village in Makati for years even when they can afford to buy 10 of them.

So the reality is that when vested interest groups ask the government to undertake mass housing projects to fill in an imagined demand gap for a cosmetic goal of social justice, the real issue is the transfer of resources from taxpayers to politically connected business firms, bureaucrats and to some welfare beneficiaries.

My guess is that the ongoing leveraging by players in the property sector whom has access to the banking system may be acquiring properties from the 68% of households and selling these projects to the same high end sector whom have been speculating both in stocks and in properties

Figure 9 US Homeownership rates

At the end of the day political demand via interventions to attain homeownership goals by blowing bubbles usually end up with the opposite effect. This can be seen in Figure 9[10]

The US experience should be a valuable example where homeownership rate has plunged to almost the 1995 levels even as homeownership programs spanned from different administrations[11].

Property bubbles will hurt both productive sectors and the consumers. Property bubbles increases input costs which reduces profits thereby rendering losses to marginal players but simultaneously rewarding the big players, thus property bubbles discourage small and medium scale entrepreneurship. Property bubbles can be seen as an insidious form of protectionism in favor of the politically privileged elites.

Property bubbles also reduces the disposable income of marginal fixed income earners who will have to pay more for rent and likewise reduces the affordability of housing for the general populace.

Outside the ethics of the property bubbles, the mania as shown by chronic overconfidence by industry participants, nominal prices of real estate at 1997 highs and signs of rising vacancy rates could be seen as a potential red flag especially if the bond vigilantes will reassert their presence.