The Philippine central bank, the Bangko ng Pilipinas (BSP) released its 2nd quarter inflation report last week.

And as expected, the BSP, which interprets the same statistical data as I do, sees them with rose colored glasses. On the other hand, I have consistently been pointing out that beneath the statistical boom based on credit inflation, has been a stealth dramatic buildup of systemic imbalances

BSP Predicament: Strong Macro or Fed Policies?

In a special segment of the report, the BSP recognizes of the tight correlation between US Federal Reserve policies and the price action of the local stock market (as noted above)

The BSP implicitly infers of the influence or the transmission mechanism of the actions of the US Federal Reserve (FED) on foreign portfolio flows to emerging markets, such as the Philippines, by stating that Fed policies “followed generally by upward trends in portfolio investment inflows”.

The BSP also sees portfolio flows as having contributed to the recent stock market boom, “A similar trend was observed with the Philippine stock exchange index; that is, QE announcements were followed generally by an increasing trend in prices, with varying lags.”[1]

And when the jitters from the FED “taper” surfaced on the global markets late May, the BSP admits that foreign funds made a dash for the exit door, “In May 2013, portfolio investment flows registered a net outflow of US$640.8 million, a reversal from the previous month’s inflow of US$1.1 billion. Net capital flows for the period 3-14 June 2013 have recovered somewhat to US$65.13 million”

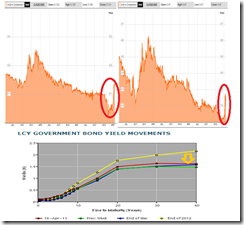

The BSP also noted that the sudden reversal of sentiment affected other Philippine markets, particularly

a) Philippine credit outlook represented by credit default swap (CDS), “The credit default swap (CDS) index exhibited a widening trend to 157 bps on 24 June after trading below 100 bps in the past month, as the market increased its premium in holding emerging market bonds. The country’s CDS narrowed to 145 bps as of 25 June 2013, improving further to 139 bps by 27 June 2013” and

b) The currency market, “the peso weakened significantly by 6.36 percent year-to-date against the US dollar, closing at a low of P43.84/US$ on 24 June 2013. Subsequently, the peso began to recover, closing the quarter at P43.20/US$ on 28 June 2013.”

The BSP dismissed the domestic market’s convulsion as having “overreacted to some extent”, and put a spin on a recovery “are now beginning to bounce back”.

But curiously the BSP justifies the selloff as having a beneficial effect of “reducing the build-up of stretched asset valuations and in making the growth process more durable in long run”, this predicated on the “inherent strength of Philippine macroeconomic fundamentals”.

See the contradictions?

If the BSP thinks that the domestic market’s reactions to external forces reduced the “build-up of stretched asset valuations”, which essentially represents an admission of overpriced domestic markets, then what justifies significantly higher markets from current levels?

And in my reading of the BSP’s tea leaves, domestic markets should rise but at a gradual pace to reflect on the “growth process” over the “long run”.

But this hasn’t been anywhere true in the recent past where mania has dominated sentiment.

The BSP doesn’t explain why markets reached levels that “stretched asset valuations” except to point at foreign portfolio flows (which they say has been influenced by the external or US policies).

And similarly in the opposite spectrum, the BSP doesn’t enlighten us why markets “overreacted to some extent” except to sidestep the issue by defending the ‘stretched’ markets with “strong macroeconomic fundamentals”.

Basically the BSP connects FED policies to rising markets, but ironically, sees a relational disconnect from a threat of a reversal of such external factors, banking on so-called strong “macroeconomic fundamentals”.

The BSP, thus, substitutes the causality flow from the FED to domestic macroeconomic fundamentals whenever such factors seemed convenient for them.

Notice that the May selloff hasn’t been limited to the stock market, but across a broad range of Philippine asset markets, which the BSP acknowledges, specifically, domestic treasuries, local currency (Peso) and CDS. Yet if ‘macroeconomic fundamentals” were indeed strong as claimed, then there won’t be ‘overreactions’ on all these markets.

And it would be presumptuous to deem actions of foreign money as irrational, impulsive, finical and ignorant of “macroeconomic fundamentals”, while on the contrary, latently extolling the optimists or the bulls as having the ‘righteous’ or ‘correct’ view.

The BSP also misses that the point that the impact by FED policies, and more importantly, their DOMESTIC policies, has not only influenced the stock market, but other asset prices and the real economy, as well, via credit fueled asset bubbles.

Central banks have become the proverbial 800 lb. gorilla in the room for the interconnected or entwined global financial markets.

Take the Peso-Euro relationship. The balance sheet of the European Central Bank (ECB) began to contract in mid-2012 (right window[2]), which has extended until last week[3].

On the other hand the balance sheet of the BSP continues to expand over the same period[4]. The result a declining trend of the Peso vis-à-vis the euro (left window[5]).

The Peso-Euro trend essentially validates the wisdom of the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises who wrote of how exchange rates are valued[6],

the valuation of a monetary unit depends not on the wealth of a country, but rather on the relationship between the quantity of, and demand for, money

The BSP seem to ignore all these.

And because today’s artificial boom has been depicted as a product of their policies, the BSP thinks that the market’s politically correct direction can only be up up up and away!

Cheering on Unsustainable Growth Models

The BSP cheers on data whose sustainability has been highly questionable.

On the aggregate demand side, the BSP admits that household spending growth has been at a ‘slower pace’.

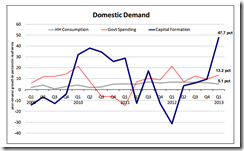

With slowing household, the biggest weight of the much ballyhooed statistical growth of domestic demand has been in capital formation. This has been attributed to the massive expansion in construction (33.7%) and durable (9.4%) equipment, and in public (45.6%) and private (30.7%) construction[7]

As pointed out in the past, construction and construction related spending has all been financed by a bank deposit financed or credit fueled asset bubbles.

The other factor driving demand has been government demand or public spending.

As I have been pointing out, this supposed growth in demand via government deficit spending means more debt and higher taxes over the future. Frontloading of growth via debt based spending signify as constraints to future growth.

Pardon my appeal to authority, but surprisingly even a local mainstream economist, the former Secretary of Budget and Management under the Estrada administration and current professor at University of the Philippines[8], Benjamin Diokno, acknowledges this.

In a 2010 speech Mr Diokno noted that[9]

Deficit financing leads to lower investment and, in the long run, to lower output and consumption. By borrowing, the government places the burden of lower consumption on future generations. It does this in two ways: future output is lowered as a result of lower investment, and higher deficits now means higher debt servicing thus higher taxes or lower levels of government services in the future.

The above debunks the populist myth which views the Philippine economy as having been driven by a household consumption boom[10].

The aggregate supply side dynamics mirrors almost the same as the above—bank deposit financed credit fueled asset bubbles.

While agriculture has pulled down or weighed on the growth statistics, production side expansion has been largely led by construction (32.5%) and manufacturing (9.7%).

On the service sector side, financial intermediation (13.9%) led the growth, followed by real estate and renting (6.3%) and other services (7.6%)[11].

In short, except for manufacturing, most of the supply side growth has centered on the asset markets (real estate and financial assets).

These booming sectors, which has benefited a concentrated few who has access to the banking system and or on the capital markets, have mostly been financed by a massive growth in credit. Yet this credit boom has fundamentally been anchored on zero bound interest rates policies.

The reemergence of the global bond vigilantes have been threatening to undermine the easy money conditions that undergirds the present growth dynamic, a factor which ironically, the BSP seems to have overlooked, and intuitively or mechanically, apply the cognitive substitution over objections or over concerns on the risks of bubbles with the constant reiteration of: “strong macroeconomic fundamentals”—like an incantation. If I am not mistaken the report noted of this theme 4 times.

And yet the recent market spasms appear to have been a drag on credit growth of these sectors (although they remain elevated).

And as noted last week, the rate of credit growth on financial intermediation, so far the biggest contributor of the services sector, has shriveled to a near standstill (1.45% June 2013)[12]. Financial intermediation represents 9.73% share of the total supply side banking loans last June.

This should translate to a meaningful slowdown for the growth rate of this sector over the next quarter or two.

It remains unclear if the growth in the other sectors will be enough to offset this. But given the declining pace of credit expansion in the general banking sector lending activities, particularly in sectors supporting the asset boom, growth will likely be pared down over the coming quarters.

So far the exception to the current credit inflation slowdown as per June data, has been in mining and quarrying (85.66%), electricity gas and water (13.84%), wholesale and retail trade (15.74%) and government services—administration and defense (17.11%) and social work (47.21%)—however these sectors only comprise 31% of the production side banking loan activities. Half of the 31% share is due to wholesale and retail trade; will growth in trade counterbalance the decline in the rate of growth of financial intermediation?

Interestingly, the BSP does not provide comprehensive data on bank lending except to deal with generalities. And puzzlingly, the BSP report has been absent of charts on the bank loans and money supply aggregates such as M3, which like the banking loans, the latter has been treated superficially. Why?

So far market actions in the Phisix and the Peso appear to be disproving the BSP’s Pollyannaish views.

Asia’s Credit Trap

The financial markets of Asia including the Philippines appear to be ‘decoupling’ from the Western counterparts, particularly the US S&P (SPX) and Germany (DAX) where the latter two has been drifting at near record highs.

Has the nasty side effects of “ultralow rates” where Southeast Asian economies, as Bloomberg’s Asia analyst William Pesek noted[13], “didn’t use the rapid growth of recent years to retool economies” been making them vulnerable to the recent bond market rout?

The appearance of current account surplus, relatively low external debt, and large foreign reserves, doesn’t make the Philippines invulnerable or impervious to bubbles as mainstream experts including local authorities have been peddling.

Japan had all three plus big savings and net foreign investment position[14] or positive Net international investment position (NIIP) or the difference between a country's external financial assets and liabilities[15], yet the Japanese economy suffered from the implosion of the stock market and property bubble in 1990 (red ellipse).

As legacy of bailouts, pump priming and money printing to contain the bust, Japan’s political economy presently suffers from a Japanese Government Bond (JGB) bubble.

And given the reluctance to reform, the negative demographic trends, and the popular preference of relying on the same failed policies, the incumbent Japan’s government increasingly depends on surviving her political economic system via a Ponzi financing dynamic of borrowing to finance previously borrowed money (interest and principal) where debt continues to mount on previous debt. Japan’s public debt levels has now reached a milestone the quadrillion yen mark[16], which has been enabled and facilitated again by zero bound rates.

And this strong external façade has not just been a Japan dynamic.

China has currently all of the supposed external strength too, including over $3 trillion of foreign currency reserves, NIIP of US $1.79 trillion (March 2012[17]).

But a recession, if not a full blown crisis from a bursting bubble, presently threatens to engulf the Chinese economy.

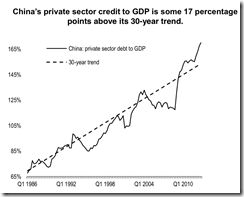

As growth of “new” credit sank to a 21 month low where new loans grew by ‘only’ 9% in July and ‘only’ 29.44% y-o-y[18], the Chinese government via her central bank the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) continues to infuse or pump ‘money from thin air’ into the banking system[19].

Such actions can be seen as bailouts by the new administration on a heavily leverage system.

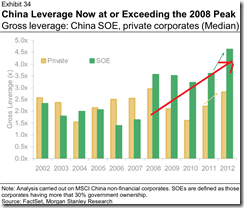

Incidentally, debt of China’s listed corporate sector stands at over 3x (EBITDA) earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization[20]. Notice too that listed companies from major Southeast economies (TH-Thailand, ID-Indonesia, and MY-Malaysia) have likewise built up huge corporate debt/ebitda.

State Owned Enterprises (SoE), their local government contemporaries and their private vehicle offsprings plays a big role in China’s complex political economy. Hence, latent bailouts targeted at these companies have allowed for the ‘kicked the can down the road’ dynamic. China recently announced a railroad stimulus[21], again benefiting politically connected enterprises.

I cast a doubt on the recent reported 5.1% surge in in export growth[22] considering her recent propensity to hide, delete or censor data[23]. These claims would have to be matched by declared activities of their trading partners. Nonetheless, eventually markets will sort out the truth from propaganda.

The point is that Asian economies have become increasingly entrenched in debt dynamics in the same way the debt has plagued their western contemporaries.

And the deepening dependence on debt as economic growth paradigm puts the Asian region on a more fragile position.

Asia is in a ‘credit trap’ according to HSBC’s economist Frederic Neumann[24]. Asian economies have traded off productivity growth for the credit driven growth paradigm, where Asian economies have “become increasingly desensitized to credit”. Yet lower productivity growth will mean increasing real debt burdens.

And if the bond vigilantes will continue to assert their presence on the global bond markets, then ‘strong macroeconomic fundamentals” will be put to a severe reality based stress test.

And the validity of strong macroeconomic fundamentals will also be revealed on charts.

Risk remains high.

[1] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Inflation Report, Second Quarter 2013, BSP.gov.ph p. 37-41

[2] JP Morgan Asset Management Weekly strategy report – 28 January 2013

[3] Reuters.com ECB balance sheet shrinks to 2.391 trillion euros, August 6, 2013

[4] see Phisix: BSP’s Tetangco Catches Taper Talk Fever July 29, 2013

[5] Yahoo Finance PHP/EUR (PHPEUR=X)

[6] Ludwig von Mises Trend of Depreciation STABILIZATION OF THE MONETARY UNIT—FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF THEORY On the Manipulation of Money and Credit p 25 Mises.org

[7] BSP op. cit., p.9-10

[8] Wikipedia.org Benjamin Diokno

[9] Benjamin Diokno Deficits, financing, and public debt UP School of Economics.

[10] see Phisix: The Myth of the Consumer ‘Dream’ Economy July 22, 2013

[11] BSP op. cit., p.19

[12] see Phisix: The Impact of Slowing Banking Loans August 5, 2013

[13] William Pesek Specter of Another Bond Crash Spooks Asia, June 7, 2013

[14] Bank of Japan Japan's International Investment Position at Year-End 2012, May 31, 2013

[15] Wikipedia.org Net international investment position

[16] see Japan’s Ponzi Finance: Public Debt Tops Quadrillion Yen Mark! August 10, 2013

[17] China Daily China's intl investment position reaches $1.8t July 14, 2012

[18] Bloomberg.com China’s Credit Expansion Slows as Li Curbs Shadow Banking August 10, 2013

[19] China Daily China central bank continues liquidity injection August 6, 2013

[20] Businessinsider.com 17 Reasons Why Experts Are Convinced China's Economy Is Doomed, July 15, 2013

[22] Bloomberg.com China Trade Rebounds in Further Sign Economy Stabilizing August 8, 2013

[23] see China’s Government Hides, Deletes and Censors Economic Data, July 5, 2013

[24] AsianInvestor.net Asia in a credit trap, warns HSBC's Neumann August 8, 2013