Once any attempt is made by the central bankers to slow down or stop the monetary expansion in the face of worsening price inflation, the entire house of cards begins to crumble. The boom turns into the bust, as investments undertaken and jobs created are discovered to be the misdirected outcome of money creation and the unsustainable patterns of demand and employments that could last only for as long as the inflationary spiral was kept going. Professor Richard M. Ebeling

Will a Yearend Rally Take Off?

November and December has largely been seen by the consensus as months favoring stock market investments. Some have classified them as Year-end rallies[1] or Christmas or even Santa Claus (late December) rallies[2]

Such rallies have been in anticipation of increased liquidity (from bonuses and gifts), also from a rebalancing of portfolios (partly from tax purposes) and or from mere optimism for the coming year—the January effect[3].

For the Phisix, since 1985, the November-December window reveals that the Phisix has risen 75% of the time during the past 28 years.

But digging through the numbers divulges some interesting insights.

One, the best returns have been during tops (1986*, 1988*, 1993 and 2006)

*1987 and 1989 I consider as quasi bear markets or countercyclical bear markets within a structural bull market. Both bear markets had been political incited (1987 and 1989 coup), posted significant losses of over 50%— 1987 (-53%) and 1989 (-63%)—and both lasted less than a year, specifically 5 months and 11 months respectively[4].

Two, the biggest returns can also be seen during sharp bear market rallies (1987, 1998**, 2000** and 2001**)

**1998, 2000 and 2001 signified as ephemeral countercyclical bull markets within a structural bear market.

Three, since the new millennium, the seasonality effects from the November-December window have greatly been subdued.

Has deepening connectivity via the cyberspace invoked a crowded trade effect (diminished arbitrage opportunities from most participants expecting everyone to do the same thing)?

Incredibly, the massive run by the Phisix from the nadir of the late 2008 of about 1,700 until the fresh historic highs in May of 2013 at 7,400 for a 335% return for 5 years+ period, has only generated November-December returns of +6.65% for 2009, -1.58% for 2010, +.88% 2011 and last year’s 7.16%.

This means that while stocks may rise over the said period, there is no guarantee, in contrast to popular expectations, that returns for the yearend season to be significant to offset underlying risk factors.

Of course qualitative dynamics of the past hardly resemble today’s conditions for us to rely on empirical data to accurately project future conditions. Said differently, this means that while stocks rose 75% of the time for the past 28 years, the largely downplayed negative returns of 25% over the same period, may also be an outcome.

The unfolding present conditions will determine the direction of price trends rather than from seasonal or historical variables.

The Nikkei-Phisix/SET Pattern

Yet the bullish consensus has been said to view the current consolidation phase as a replica of 2011 in expectations of a major leg to the upside.

Pattern seeking to justify one’s belief is easy.

The year to date chart of the Phisix (left upper window) and Thailand’s SET (right upper widow) looks as they have been behaving in proximate symmetry.

Both have earnestly been attempting to untangle themselves from the twin May-June and August bear market strikes.

Curiously both charts, the year-to-date Phisix and the SETI charts appear to closely approximate what seems as a bigger paradigm, Japan’s major equity bellwether the Nikkei 225 from 1985-1995 (red square).

Yet the succeeding events from the Nikkei’s incipient downfall had been an unpleasant one. In the wake of the 1990 crash where the Nikkei fell by 60% from the pinnacle of 38,916, after a long period of consolidation (1993-1997), the major Japanese equity bellwether plumbed to new depths. The Japan’s lost decade has been underscored by the Nikkei’s 80% loss over a 13 year period.

Since the all-time low of 7,831.42 in March 2003, the Nikkei has been rangebound from 8k to 18k. Even with Abenomics in place, the Nikkei at the 14,000+ levels has still been in a considerable distance from the June 2007 high of 18,138.36.

If the Nikkei’s pattern evolves similarly on the Philippines and on Thailand, then this would hardly be “bullish”.

Will a firming US Dollar be a Spoiler?

As I have been repeatedly saying, financial markets of emerging markets (which includes emerging Asia) will generally depend on the conditions of the bond vigilantes

Rallying US Treasuries (declining yields) appear to have hit a wall. The US dollar has recently strengthened amidst the manic episode in the US equity markets.

In May, the sharply strengthening US dollar peaked along with the Phjsix (PSEC), Emerging Markets (EEM) and the FTSE ASEAN (ASEA) bellwethers. The rally in the US dollar coincided with an unexpected surge in yields of US treasuries.

It was also in May when the financial markets began to speculate on the impact of both Abenomics and more significantly Bernanke’s Taper talk. The financial markets came to believe that even a minor reduction of US liquidity would have an adverse impact on financial markets and the economy.

By June, global stock markets fell hard. Many emerging markets had been pushed to bear market levels. China suffered its first bout of liquidity squeeze[5]. While the US dollar rallied strongly against emerging markets, the US dollar fell against developed market contemporaries.

The sharp second spike in the US dollar (second green rectangle) in response to the continuing stress in the financial markets, corresponded with what seemed as an orchestrated communications campaign launched by central bank officials in pushing back the market’s concern over the Taper[6].

As equity markets of emerging markets partially recovered on assurances from central bankers, which has signalled a return of the quasi-Risk ON environment, the US dollar failed to sustain its advance and consequently declined dramatically.

However by August the rally in the equity markets of emerging markets hit a wall. Renewed concerns over the taper, uncertainty over Ben Bernanke’s replacement and the Syrian standoff emerging market sent stocks reeling[7]. Such uncertainties propelled the US dollar index higher for the third time.

But again this wouldn’t last as central bank officials come to the “rescue”.

The FED surprised the markets heavily expecting a tapering with an UN-Taper announcement[8]. Stocks in developed economies run amuck and went into a blowoff phase. Debt ceiling deal and Ms. Janet Yellen’s anointment as Bernanke’s replacement further fired up the melt-UP mode[9]. This US stock market bidding frenzy continues until today.

Some of this optimism has diffused into select emerging markets. The US dollar tumbled once again.

The wild volatility swings prompted by action-reaction feedback mechanism between, on one side, the central bankers and political authorities, and on the other, the financial markets continues.

Amidst a continuing meltup mode by US equities, the oversold US dollar staged a massive comeback this week. This has been accompanied by a renewed selloff in US treasuries as well as in commodities.

The question is will US treasury selloff and the US dollar rally be sustained? If so what could be the implications?

How the US dollar may affect the US-ASEAN equity correlation?

Changes in the direction of the US dollar index have demonstrated some correlation with the performance of US stocks relative to ASEAN contemporaries.

With a 2-3 months lag, the rise of the US dollar (February to June) eventually coincided with outperformance of the S&P 500 over the Phisix (SPX:PSEC; window below USD index), S&P 500 over Thailand’s SET (SPX: SETI) and S&P 500 over Indonesia’s IDDOW (SPX: IDDOW; lowest pane).

When the US dollar peaked in July and turned lower until last week, the SPX’s outclassing of the ASEAN stocks seems to have also culminated (blue line).

If such trend should continue, then we can expect the following

-ASEAN stocks can go higher vis-à-vis the US (but count me as doubtful)

-Even if ASEAN equities continue to consolidate or move sideways, ASEAN outperformance could mean a coming correction in US stocks.

-Since the above represents a ratio between two indices, even if both the S&P and ASEAN bellwethers posted declines, for as long as the degree of contraction by ASEAN equities is smaller than the S&P the ratio will favor ASEAN. The charts indicated (S&P: ASEAN) will reveal a downside motion.

But I lean towards a coming US stock market correction.

I have been pointing out how market participants have frenetically bid up US stocks by indulging in record high net margin debt, wallowing in debt financed share buybacks[10] and splurging on massive leveraging on indirect speculative activities

This comes amidst declining rate of growth in terms of net income and earnings, as well as, manipulations of earnings guidance[11] in order to justify such a mania.

I have noted that PE ratio of US stocks as embodied by the small cap Russell 2000 has reached shocking 80+ levels.

I have also alluded to substantial cash raising activities by foreign investors and by many celebrity and market gurus in anticipation of a major pullback.

Even the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, Norway’s Norges Bank Investment Management has joined this bandwagon and recently warned of an impending reversal or “correction” of stock markets[12].

On the other hand, retail investors have been piling in as US stocks goes vertical.

It’s also important to realize that when major US equity benchmarks move farthest from each other, the outcome has been significant retrenchments or bear markets.

The S&P (red) pulled away from the Dow Industrials (green) and the Russell 2000 (blue line) in the dotcom bubble days, the corollary had been a dotcom bust.

In 2007, the small cap Russell 2000 meaningfully surpassed the Dow Industrials (green) and S&P (red) by a mile. The patent discrepancies eventually paved way for a bear market which has been triggered by a housing bubble bust.

The same can be seen in 2011, where huge divergences (but over a short period) led to a significant correction.

Today such incongruities have not only been colossal but have also been critically extended as earlier discussed[13].

But what if the US dollar index continues to climb?

The most likely answer is that in 2-3 months after, we can expect another round of outperformance by US equities relative to ASEAN.

Again this may not necessarily mean rising markets. The S&P 500 fell along with ASEAN markets in August, but again the decline was lesser in scale relative to the ASEAN bourses which endured the second strike from the bears. The August selloff resulted to the zenith of the SPX:ASEAN ratio

This means that if the US dollar should rise further, then this extrapolates to bigger fragility for emerging markets and for ASEAN.

Indonesia Remains Vulnerable

ASEAN’s vulnerability can be seen from developments in Indonesia

The recent seemingly tranquil pseudo-risk ON period has hardly pacified Indonesia’s mercurial financial markets.

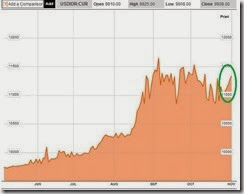

It has failed to dampen the elevated conditions of Indonesia’s currency, the rupiah.

In addition, “dramatically increased the cost of living” has prompted labor unions and workers to hold a nationwide strike to demand a FIFTY 50% increase in minimum wages.

In Jakarta, this comes on top of earlier minimum wage hike of 42% in less than a year[14]

Yesterday, a first batch of a dozen Indonesian governors agreed to increase minimum wages by an average of 19%. Later in the day, another batch announced higher minimum wages from anywhere between 10-45%[15].

So rising minimum wages will compound on the drag effects on Indonesia’s real economic growth.

And to think just a year back Indonesia has been a darling of credit rating agencies[16].

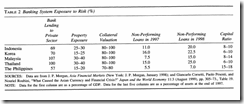

While Indonesia’s inflation woes has been blamed on the partial lifting of oil subsidies (subsidies I earlier noted accounts for 3% of the GDP[17]), Indonesia’s main predicament has been due to unwieldy government spending, interventionist populist government (as shown by minimum wages) and massive credit expansion both to the private and government as measured by Indonesia’s external debt.

These has prompted for trade deficits and a blowout in current account deficits[18]

In short, the Indonesian economy reveals of the priority to spend financed by debt rather than to produce and generate savings and increase productivity[19].

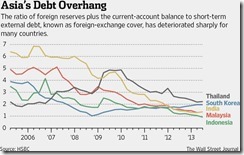

Indonesia’s foreign currency stockpile has been eroded by 23.2% to USD 95.675 million as of September 2013 from a high of USD 124.637 in August of 2011 mainly from defending the rupiah.

This compares to the USD 83.029 million for the Philippines as of September which also appears to be in a downshifting trend. From the record high in January 2013 Philippine foreign currency reserves has declined by 3.2% as of September.

The above only exhibits how the rupiah appears highly vulnerable to a crisis from a sustained surge in the US dollar and or extended selloffs in US treasuries.

This also shows how the damage from the bond vigilantes has percolated into the real economy.

And the recent rebound of Indonesia’s stock market appears to have ignored all these risks.

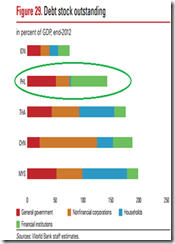

Curiously, Indonesia has a low government debt to GDP level (23.1% 2012) even lower than the Philippines at (40.1% 2012)

And it has not just been government debt but likewise overall debt standings which I previously shown where Indonesia’s debt exposure has been the lowest among ASEAN peers and China.

As a reminder, relative low debt levels by the Philippines or even by Indonesia didn’t spare these countries from a regional contagion when the Asian crisis hit in 1997[20].

The point of the above is that vulnerabilities to a debt crisis may emanate from different soft spots in the economy. This means relative debt levels hardly represents an accurate measure for measuring risks without understanding the interconnectedness and interdependencies of different sectors of an economy.

Yet it isn’t relative debt levels but rather confidence levels by creditors on the ability or willingness of a country to honor their liabilities.

External factors like a surge in the US dollar or rampaging bond vigilantes may expose such weakness.

Bottom line: ASEAN stocks and or the Phisix may rise mainly out of the desire to stretch for yields, but substantial risks remain. Potential tinderboxes as China (as explained last week), Japan, the US, Europe, India or even ASEAN would make global stock markets highly vulnerable to black swans especially amidst the unsettled bond vigilantes.

[1] The Free Dictionary Year-End Rally

[2] Investopedia.com Santa Claus Rally

[3] The Free Dictionary January Effect

[4] See Phisix: Don’t Ignore the Bear Market Warnings June 30, 2013

[5] See Emerging Market Rout: Prelude to a Global Crisis? June 17, 2013

[6] See Phisix: The Myth of the Consumer ‘Dream’ Economy July 22, 2013

[7] See Histrionics of US Politics: Markets in Buying Orgy on Hopes of Debt Ceiling Deal October 11, 2013

[8] See Asian Markets Jump on the FED’s 'Untapering' or QE extension September 19, 2013

[9] See Phisix: US Debt Ceiling Deal and UNTaper Spurs a Global Melt UP October 21, 2013

[10] see Phisix: Rising Systemic Debt Erodes the Margin of Safety October 14, 2013

[11] see Phisix: The Implication of the US Boom Bust Cycle October 28, 2013

[12] Bloomberg.com Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Shuns Stocks on Reversal Bet October 26, 2013

[13] See More on Russell 2000s Outrageous Valuations October 29, 2013

[14] Wall Street Journal Indonesians Strike for Higher Wages October 31, 2013

[15] Wall Street Journal Indonesia Governors Boost Minimum Wage, November 1, 2013

[16] see Phisix: Moody’s Sees Bubbles as Structural Shift to Higher Growth October 7, 2013

[17] See Phisix: Will the Global Equity Meltup be Sustainable? September 16, 2013

[18] Tradingeconomics.com INDONESIA CURRENT ACCOUNT

[19] See Is Indonesia ASEAN’s Canary in the Coal Mine? August 2, 2013

[20] Marcus Noland, The Philippines in the Asian Financial Crisis: How the Sick Man Avoided Pneumonia, University of California Press 2000