[note I am having difficulties in the posting of this blog for unknown technical reasons on my windows writer. So I used direct posting via blogger, which has so far, resulted to below expectations performance. So pardon me for the abnormalities. Thanks]

Activities in the Philippine stock exchange reveal that the mania phase has not only gotten a second wind but appears to intensify far more than the initial phase.

Between the manic episodes from 2013 and 2014, a similar 45° slope has been formed. What took 5 months for a near vertical “parabolic” lift off in 2013[1] has taken only less than three months for the current version.

Of course the degree of gains has been different; about 26% in 2013 vis-à-vis 12% in 2014. But the slope reveals of the desperate and violent “resistance-to-change” attitude from the attempt to resurrect the old scenario.

And market internals also exhibit how activities the Philippine Stock Exchange has reached levels considered as excessively overbought conditions and reeks of severe overconfidence which has been expressed via ludicrously mispriced valuations.

In terms of flows, peso volume has recaptured the gist of previous denial rallies (left pane). This by no means is a negative indicator. But it shows the rather fickle flow of trading volume dependent on the direction of the markets.

However, the current mania, which has been backed by foreign money flows, seems to have reached levels again that have highlighted major correction phases. The blue ellipses demonstrate the levels in the surges of foreign money flows that coincided with interim market tops.

In the context of sentiment, the same holds true where (weekly) average number of trades and (weekly) average number of issues traded exhibits acute inflation of overconfidence.

The average daily trade (left) has reached the February 2013 levels which produced a 5% correction. Such has been indicative of new participation and or aggressive momentum based churning by existing players.

The average number of issues traded (right), which means retail trades bidding up the broader market (third tier non-liquid issues), has surpassed previous denial rallies and remains elevated despite this week’s slight retracement. Although the broad based bullishness has yet to reach the February and May levels.

Again the difference between the time zone of February to May and today’s rally is that the former represents bullish conditions (tailwinds) from strong currency and zero bound rates as against today’s bear market rally amidst opposing conditions (headwind).

The seeming resemblance has been from the current participants’ attempt at restoring or reviving the old order even under a starkly distinct environment.

To fittingly quote Black Swan theorist, author, philosopher and my favorite iconoclast Nassim Nicholas Taleb[2],

Never rid anyone of an illusion unless you can replace it in his mind with another illusion

More Incredible Embrace of Delusions

And allow me to delve deeper into what has been part of the worship of bubbles as vented through outrageously mispriced Philippine stocks.

First let me put on the mainstream thinking hat which sees no risks of a Black Swan and where growth will be sustained but at an undermined rate.

The following table signifies the compilation of the nominal (non-inflation adjusted) earnings per share (eps) based on Philippines Stock Exchange data from 2010 until 2013[3] of the 20 of the 30 Phisix component issues. My selection initially came about from what seems as lofty Price earnings ratio based on 2012 data.

I used three categories in evaluating the changes in eps. First is the average eps for the 4 years. Next is the Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) covering the same period. And finally the % change from 2013 to 2012 where I attempt to identify the extent of contribution of the 2012-2013 relative to the 4 year CAGR. The reason for the latter? 2013 saw a fantastic surge in money supply, and as I point out below, surges in money supply has influence in buttressing of high profit levels.

From the eps covering 2010-2013, the green filled data exhibits a sustained rise in eps. The yellow filled data represents the succession of declines of eps for specific companies.

Yet it seems ironic to see declines in Globe Telecoms [GLO] in four successive years (that has a 4 year CAGR of -22.97%) and SM Prime Holdings [SMPH] over 3 continuing years (that has a CAGR of -12.17% and is not in the table above), produce an uptrend in their respective prices or positive returns. GLO today, drifts just off the 2007 highs. SMPH soared to a record high in June 2013 but has been significantly down by about 30% from the highs. Based on this eps numbers alone, how has declining growth rate of eps been supportive of record or near record prices? Bad news is good news? What has become of the markets?

Based on 2013 eps, at Friday’s close, per for GLO is at 62.74 while SMPH is at 35.1!!!

And in the CAGR column we note that only a few companies have far exceeded the 15% threshold marked by blue (above 20%) and orange (above 15%).

This includes holding companies of Alliance Global [AGI], DMC Holdings [DMC], newly listed LT Group [LTG], coal mining Semirara [SCC] and property developer Ayala Land [ALI].

Interestingly the huge growth rates in the CAGR have mostly been driven by a surge in eps from 2013-2012. For instance 50.67% of the 4 year CAGR for AGI emanates from the spectacular 80.77% growth of the firm’s eps in 2013. The same goes for DMC where the 74.62% jump in 2013 eps lifted the 4 year CAGR to 26.11%. This implies that 49.66% of the 4 year CAGR emanates from the 2013 growth rate alone. And so forth.

As a side note, I found out that the probable reason for the 75% spike in DMC’s eps may have emanated from a non-recurring one-time sale of 15.74% share in Manila Water Corporation to a consortium Marubeni Corporation - Nippon Koei Ltd (MCNK) for the amount of Php 10.2 billion[4]. So if I apply a 15% growth rate to DMC’s 2012 earnings, Friday’s pe ratio of 10.03 will balloon by half to 15.23. I am not aware of the anomalies of the others.

And if I apply standard deviation (based on the 2010-2012 eps) to compare with 2013 eps, using the normal distribution curve, AGI and DMC aside from JFC will account for “5 sigma events”, particularly 4.417 σ (99.999% measure of confidence), 4.892 σ (99.9999%) and 3.291 σ (99.9%) respectively, or fat tails[5].

In short, the Philippine stock market seem to have bought into the idea that statistical outliers or fat tails will become the new normal.

And if you look at the pe ratio of Friday’s close relative to 2013 eps (which ranges from 10-63), the 18 companies has an average 26.84 pe!!! And if I apply average of the 4 year eps, at Friday’s closing prices the average pe for the 18 companies stands at an astounding 31.94!!!

And above is an example of the PER of Philippine consumer stocks.

Top of the honor roll of stupendously overpriced issues are liquor company Emperador Inc [EMP], recently listed Robinson’s Retail Holdings [RRHI] comes second at 43.02 and ‘hypermart’ retail Puregold [PGOLD] at 34.84. Even if we assume that statistical final consumption HIFE (Household Final Consumption Expenditure) grows at 10% (in 2013 HIFE clocked at 7.9% at current prices as per NSCB), what justifies price level growth at current levels?

And all these have been premised from the perspective that growth will be sustained. But what if a Black Swan event occurs?

The market has now come to believe in impossible things.

The Natural Limits to Profit Growth

There are natural limits to profit growth

The law of compounding restrains any high growth rate in earnings.

Take for instance a growth rate of 15% means doubling of earnings in 5 years. If a company earns at 15% growth perpetually then the company’s earnings will far exceed GDP (assuming the latter is < than eps growth rate). So any outgrowth will extrapolate to future mean reversions.

Next, competition should drive profits lower as new players participate in the hope to partake of a share in the high profit environment.

As the great Austrian economist Hans Sennholz explained[6]

Contrary to popular belief, pure profits are only short-lived. Whenever a change in demand, supply, fashion, or technology opens up an opportunity for pure profits, the early producer reaps high returns. But immediately he will be imitated by competitors and newcomers. They will produce the same good, render identical services, apply similar methods of production, and thus depress prices until the pure profit disappears. The first hula-hoop manufacturer undoubtedly reaped pure profits. But as soon as dozens of competitors had retooled their factories the market was flooded with hula hoops. Prices dropped rapidly until the pure profits had vanished

So the fantastic expansion in the Philippine real estate industry for instance would mean less profit in the future for many firms due to the entry of more competition[7].

High profits are indicative of a high risk environment. Higher returns from a perceived high-profit-high risk tradeoff lures risk takers to increasingly undertake arbitraging activities under such an environment until the rate of profit diminishes. When the risk premium declines, and so will profits.

Again Professor Sennholz,

Industries that work with a minimum of risk in stable markets and with stagnant technology must expect to earn the lowest profits. When completely adjusted to consumer demand and without any anticipation of risk, pure profits would indeed be completely eliminated and only the originary interest return would remain

Profits are also determined by the lengthening or shortening of the production cycle—or the time span covering expenditures for means of production and the proceeds from the sale of final consumer goods.

As the Austrian economist George Reisman explains[8]

The principle is that, other things being equal, a lengthening of the average-period-of-production/necessary-lapse-of-time brings about a transitory decrease in aggregate costs of production in the economic system and increase in profits in the economic system. By the same token, other things being equal, a shortening of the average-period-of-production/necessary-lapse-of-time brings about an increase in aggregate costs of production in the economic systems and decrease in profits in the economic system.

The lengthening and shortening or of the production process determines the limits of profits.

And allocation of capital to the production process involves the underlying social policies affecting people’s time preferences. And this involves monetary inflation and government spending as well.

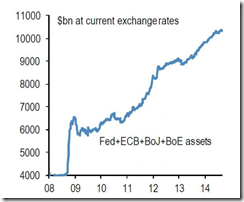

Via bubble cycles, monetary inflation also spruces up profits temporarily but eventually leads to depression.

When money is injected into the system, this raise prices relative to previously incurred business costs. Thus faster rate in the increase in prices boost sales revenues relative to historical business costs paving way for high profit rates.

But since relatively rising prices will spread in the activities supported by money growth, rising prices will also raise business costs and may eventually, but not necessarily, spillover to consumer prices. So this means high business costs and consumer prices will offset any gains from nominal high profits. This also means that for high profit rates to be sustained such would require even faster rate of monetary inflation. The 30++% in Philippine M3 underscores on the outlier profit booms for some Phisix companies.

But whatever profits gained from increases in money supply are again only nominally based and will not be beneficial to the economy.

Why? Because again according to Mr. Reisman[9],

The rise in the nominal rate of profit does not imply any increase in the real rate of profit, that is, the rate of gain in actual wealth, because the same rise in spending that raises sales revenues and profits in the economy also raises the level of prices. The extra profits are almost necessary to meet the high replacement costs of inventory and plant and equipment, and the rest are necessary to meet the higher prices of consumer goods that the owners of businesses were previously able to buy in their capacity, say, as stockholders receiving dividends. Indeed, the real rate of profit firms earn actually falls while the nominal rate of profit rises. One major reason it does so is because the additional nominal profits, while mainly necessary for the replacement of assets at higher prices, are taxed, as though they were real profits. Thus firms are placed in position in which, after paying taxes, they are actually worse off as the result of the rise in the nominal rate of profit

In other words, cosmetically high profits are essentially eroded by the inflation tax. In the case of the Philippines, high profits come amidst the deepening of stagflation.

And this is why inflationary boom are capital consuming. Not only have capital been misdirected towards speculative non-productive high order/capital intensive ventures, any gains from such undertaking are being taxed via reduced purchasing power in terms of business costs and consumer prices. And because they erode resources and wealth, they are unsustainable.

So not only will the pricing mechanism serve as natural barrier for artificially high profits from an inflationary boom, the unsustainable debt structure and the attendant amplification of risks in the monetary system will also render inflationary booms as temporal and ultimately regressive. Thus the boom-bust cycles.

Government spending via deficits also boosts profits momentarily.

As capital is diverted away from production into consumption activities by the government, the disparity from the increase in consumption activities via spending in the face of reduced business activities (via lowering of business costs) will extrapolate to higher profits.

Again Professor Reisman[10]

The average rate of profit is raised by virtue of both of the rise in the aggregate amount of profit and the reduction in the aggregate amount of capital invested. The difference between the effect of budget deficits on the rate of profit, and of taxes that reduce productive expenditure, is that in the case of budget deficits the rise in the rate of profit is a rise in the net, aftertax rate of profit, not merely in the gross, pretax rate of profit. This because in this case, there is no rise in tax costs in the economic system to offset the fall in ordinary business costs that results from the fall in productive expenditure.

Of course, just as in the case of a fall in productive expenditure caused by taxation, the decline in productive expenditure caused by budget deficits is inimical to economic progress, and, if carried far enough, must cause economic retrogression.

When businesses spend less for expansion, fewer goods and services are produced. This also means fewer jobs which also imply of depressed wages. But increased government consumption translates to higher consumer prices relative to currency’s spending power backed by reduced productivity. The implication is that high profits can be symptoms of untenable wealth distribution that leads to a lower standard of living. And anything that diminishes people’s standard of living is unsustainable.

Yet there is no singular explanation to the high profits/earnings seen in 2013 for Philippine listed companies, as they involve all the factors above at varying degrees that has boosted relative earnings to tenuous statistical outlier levels.

Importantly, whether it is statistics or theory, current price levels hardly reflects on “investments” but about unalloyed excessive speculative yield and momentum chasing or punting activities. Bluntly put; gambling in the first degree.

French writer François-Marie Arouet popularly known by his pen name Voltaire describes what seems as fitting for the current price levels,

It is difficult to free fools from the chains they revere

[2] Nassim Nicholas Taleb Additional Aphorisms, Maxims & Heuristics

[3] Philippine Stock Exchange Monthly report: December 2011, March 2012, December 2012, January 2014 (subscription required)

[6] Hans F. Sennholz Profits June 6, 2012

[10] Ibid p 829-830

.png)

.png)