We believe investors often confuse waves of capital inflows into emerging markets-when global monetary conditions are permissive and the consequent asset inflation and credit booms -with some fundamentally-driven intrinsic “growth” theme in emerging markets. There are many ebullient investment ideas we have hear d over the past 25 years: the massive infrastructure theme, the growing middle class, the nutrition/water idea, the urbanization meme, the emergence of this sub-region or the other. We remain skeptical and cynical. Eventually, these glossy investment views have run into tighter global monetary conditions, the inevitable crises, large capital losses and vows of “never again”. Until, of course, the next global monetary easing, when all is forgiven, and a fresh wave of investors wades in again. Ajay Singh Kapur, Ritesh Samadhiya,and Umesha de Silva

Bullish hopes had been rejuvenated this week as the Philippine equity benchmark, the Phisix, went into a melt up mode.

Powered by foreign buying, the Phisix leapt by 3.18%. Year to date gains suddenly tallied to 7.11% after last week’s 1.71% rally. The bulk of the annual gains had been built on from the late January surge. The advances during the last two weeks piggybacked on this despite the sporadic accounts of downside volatilities from late January.

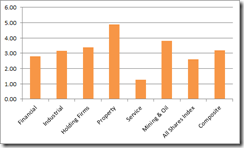

Market Breadth Highlights Fragility of Recent Run Up

Stock market bulls have latched their hopes on a sustained “high” statistical economic growth, ignoring recent developments or facts (Aldous Huxley syndrome) that unemployment data has surged in late 2013 and of the deterioration of sentiment by recent surveys on the quality of life. They would most likely see the recent rally backed by foreign flows as signs of a return to “rational” assessment by foreigners of Philippine assets.

The technically speaking, the recent rally which broke beyond the January highs will be seen as “falsification” of the “descending” triangle that has haunted and encumbered the Phisix. Yet the fact is that the late January inspired rally represents the third major attempt to push the Phisix back into bullish territory where the previous two failed.

The health of the recent rally can be measured by relative market breadth developments which are indicative of sentimental changes.

While it has been true that foreign buying may have returned to their “senses” (putting on the hat of the bulls), previous patterns of foreign flows tell us, in 2013, a different story. In the past, spikes in foreign flows (in both directions) have been accompanied by major volatile periods marked by interim peaks and bottoms (left window/ blue circles). While the recent rally has not reached levels as those with May, July and September, yet if the recent rate of foreign inflows will continue in the coming week or so, this may portent of another major interim retracement. That’s in the condition where the past will rhyme.

In addition, it would be a mistake to read foreign flows as a static or linear based dynamic. In 2013, foreign flows have mostly been mercurial characterized by drastic and substantial reversals of sentiment, particularly from June onwards. I don’t think this dynamic would stabilize anytime soon for reasons I have long stated, and for reasons I will elaborate below.

Moreover, despite the very impressive 4.89% two week swing supported by a sudden turnaround in foreign sentiment, peso volume (weekly averaged or total peso volume for the week divided by the number of trading days) has materially lagged the earlier denial rallies of July and September (right window).

In other words, in the face of the nice numerical gains, it would seem that the bulls have hardly maintained a wholehearted conviction of a sustainable upside move, or that the bulls have remained reluctant. This seems in contrast to the bears whom has used the buy-up as opportunities to exit.

We then move from flows to trades.

This week’s massive rally has been accompanied by a spike in the number of daily trades (averaged weekly or total weekly daily trades divided by number of trading days) as shown on the left diagram.

A sustained upsurge in daily trades has coincided once again with major interim tops (Feb 2013, May 2013 and July 2013). Sudden and dramatic increases in daily trades have been indicative of increases in trade churning. This implies more participation from retail participants who has bought into bullish “growth” story/spin.

Yet in every peak of stock market cycles, retail investors, who are usually the last movers into maturing runs, have usually been the last left holding the proverbial empty bag[1]. So if there should be another significant gush of churning activities in the coming week or so, then we should expect another major downside move soon. That’s again if the past will rhyme.

Such sentiment metric has hardly been any different with advance decline spread. The current run has been broad based. Weekly averaged advance decline spreads have reached levels where previous rallies has been abbreviated or accompanied by a big downside swing.

And such scale of climaxing bullish sentiment has translated into interim peaks which has been apparent in February 2013, May 2013, July 2013, October 2013 and the late January 2014 rally. So again if the past will rhyme, any sustained bullish breadth this coming week or so, would translate into a selling opportunity.

Despite the impressive gains during the past two weeks, four market breadth indicators (flow) peso volume and foreign money flux and (trade) daily trades and advance-decline spread have shown how fragile the current rally has been.

This means that while technically the declining triangle may have been invalidated (this depends really on reference points), bullish sentiment based on the above facts reveal of a largely uncommitted stance.

Excess Volatility, Market Tops and History Rhymes

Since we are into Mark Twain’s history doesn’t repeat but history rhymes, let me exhibit why I believe patterns reinforce their existence.

As a student of the business cycle and of economic history, I am convinced that this time will not be any different. Inflationism as evidenced by the symptoms—rising markets (expressive of overconfidence) driven by excessive speculation founded on rampant debt accumulation—is fundamentally unsustainable. This has been proven all throughout history and has even been documented by Harvard professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff[2]. And rising rates in the face of such untenable conditions serve as the proverbial pin that eventually that leads to what I call as the Wile E. Coyote moment (a bubble bust).

I am not a fan of simplistic pattern based analysis for one simple reason: people’s social interactions and reaction with the environment will hardly ever be constant.

But there are reasons why patterns, which can be expressed as cycles, exist.

Despite technological advances and the permeation of education, people incur the same errors. And such errors have been induced by social policies. Unfortunately a majority of people, including the so-called intellectuals, can’t seem to comprehend that the impact of regulations or of social policies has never been neutral. Social policies affect people’s incentives and behavior to such extent that people have been lead to commit the same mistakes; thus such become cycles. So for instance, when central bankers dabble with money inflation, almost similar to the way Roman emperors debased their coins[3], eventually crises occurs and society degenerates.

I have noted that bubble cycles operate on a “periphery to the core” dynamic where the zenith of bubble cycles applied to the stock market can be seen via extreme volatility or what I say as volatility in both directions with a downside bias.

I have previously demonstrated how “volatility in both directions with a downside bias” applies to the Philippine Phisix, based on the 20 years of history[4]

Applied to the US we see the same volatility dynamic at work.

In hindsight all topping process in the S&P 500 has been accompanied by “volatility in both directions with a downside bias” whether in 2007-8, 2000 dotcom bust, 1973-1975 US recession and 1929 stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression.

Like me, the source of the charts above except 2007, fund manager John Hussman who hasn’t been a fan of patterns too but notes on why patterns may become a self-fulfilling reality[5] “We would dismiss historical analogs like this if the recent market peak did not feature the “full catastrophe” of textbook speculative features – particularly the same syndrome of extreme overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield conditions observed (prior to the past year) only at major market peaks in 2007, 2000, 1987, 1972, and 1929.”

This brings us back to the Phisix in the context of a 1994-1997 top and today’s perhaps more truncated cycle. The numbers are not Elliott Wave counts, instead they are occasions when the Phisix suffered from bear market seizures.

So far, there seems to be a pattern or a resemblance between 1994-95 topping process and today’s cycles. The common denominator three bear market strikes (June, August, December 2013) and three bear market convulsions (1994-1995).

Yes I know the difference: today 5,800 has been the support, while in 1994-5 the decline has been a downside channel.

If the past should repeat then we should see a final blowoff phase rally prior to the capitulation.

Troubling Signs from Property Bubbles

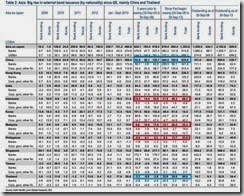

One of the troubling indicators underscoring the “this time is different mentality” is from an article touting “Who’s afraid of interest spike?”[6] noting of the largest property developer thrust to finance a major expansion program by going into the debt markets.

Last week’s rally has been inspired by the property sector largely premised on the supposed jump in the profits of Ayala Land in 2013. Company officials announced that past is the future so they will sustain a massive expansion program to be financed mostly by debt

I had wondered if truly the officials of the largest property developer expected an interest spike as the title of the article suggested.

Well it turned out to be a disappointment. The quoted official of developer said that “We have debt capacity we can utilize” and when asked how interest rates developments affected their plans the reply was “already built in to the plan”

Would a company acquire massive debts if faced with “spiking” interest rates that would jeopardize their profit position? From a rational economic position the answer would be NO. Instead the company will take on more debt because they foresee that profits will eclipse the cost of debt servicing.

So it is obvious that “built in to the plan” extrapolates to expectations for a negligible rise in interest rates. Obviously too that a “spike” in interest rates has hardly been a factor into the expectations of company’s officials in the context of demand for the company’s property products. Company officials seem to see that the finances of their customers are without limits.

The article even quotes the BSP governor who reportedly said “high liquidity in the banking system will help mitigate any increases at all.” When does “mitigate any increases” equal to “interest rate spike”?

So contra the headline of the article whose author may be impliedly sneering at cynics, the headlines represents an inaccurate and inconsistent depiction of the official stand of the property company. There hardly has been any trace of expected “spike” in interest rates.

Two reasons why these are troubling signs. The inaccurate representation of the company official’s position is a sign of media’s undiscerning promotion of bubbles. It is also a sign of illusion of superiority based on what seems as false knowledge or the Dunning–Kruger effect[7].

Two, the stock market players bidded up on property stocks based on past performance (last year’s profits) and based on the company’s optimism via a massive debt financed expansion. This means that stock market players practically threw “risk” under the bus and virtually agreed that “debt is growth”. Such signifies nauseating signs of overconfidence or reckless yield chasing speculation or both.

Where will Domestic Demand for Properties come from?

If the recent surge in unemployment rates have anywhere been accurate, and if this has been supported by deteriorating sentiment on the public’s perception in terms of quality of life standards (due to spreading price inflation), then demand for middle and lower class housing will begin to taper.

The adverse impact from inflation will also impact demand from remittance based finances or OFW dependent markets, a sector that previously contributed to an estimated one fourth of demand of the housing industry[8]. While it is true that devaluing peso means more pesos for every unit of foreign currency, such advantage will be offset by increases in domestic prices of other goods and services. As pointed before, Philippine households are mostly sensitive to changes in food, energy and housing as part of their consumption distribution basket. So a switch in spending to food and energy or even to rental would mean less money available for housing acquisition.

And if inflation intensifies and will get reflected on interest rates, there will be reduced demand for housing even to people with access to the banking system, since debt servicing will eat up a larger share of a shrinking income base, due to reduced purchasing power from an inflated peso.

This also means that any sustained boom in demand for property will largely depend now on a narrowing spectrum of markets, particularly the elite (perhaps funded via debt financed purchases) most likely for speculation (flipping) purposes, from foreigners (mostly for speculation), and from some property owners who benefited from the expansion undertaken by property developers by selling to the latter.

While it is true that high end properties may not even be price sensitive as they can perceived as “status symbol” products or Veblen Goods[9], demand for such goods will depend on the prestige behind the scarcity, and the available financing to acquire such products.

But the race to develop properties has been an industry wide phenomenon, not limited to the prime developers, so inventories have been rising faster relative to demand in almost all categories.

And rising rates from increasing signs of inflation will mean lesser availability of capital.

One demand for property boom comes from previous property owners who sold to the developers. Some may have bought into developer’s project while others may have joined the race in the snapping up of properties in the hope of flipping them again to developers. Both have contributed to higher property prices. Some have used the windfall for consumption.

Nonetheless, for such segment consumption and property speculation extrapolates to capital consumption. When developers see the light of a slowing demand, such beneficiaries will also feel the heat from financial losses once the excess from the supply side becomes apparent.

The Singapore Model for Foreign Demand of Philippine Properties?

The last dynamic driving housing demand comes from foreigners.

Experts from the housing industry said last year that new regulations and taxes in Hong Kong and Singapore in order “to curb speculation in their property markets”, drove demand for domestic properties since the Philippines have become a “more foreign-investor friendly destination”[10]

As a side note, I’d say that liberalization that led to a “foreign-investor friendly destination” has been mostly in the construction sector[11], and hardly the general economy. Like almost every government elsewhere today, the incumbent have used bubbles to spruce up statistical economic growth.

In short, what the report should have said was that speculative demand merely transferred from Hong Kong and Singapore to the Philippines.

Here is more of what they didn’t say.

Singapore’s property bubble fuelled by the Singaporean central bank’s easy money policies has essentially driven a stake into the hearts of the Singapore’s free market model[12].

The politically divisive easy money policies by Singapore’s monetary authority have made foreigners a lightning rod for politically correct populist inequality sloganeering that has raised nationalist sentiment[13]. As such, Singapore’s politics has ushered in statists leaders who has imposed welfarist programs[14], and has recently even imposed labor protectionism[15] by putting a law to prioritize on locals over foreigners.

A few days ago we see Singapore’s descent deeper into a welfare state by the imposition of sin taxes[16]. Those low tax days appear to be numbered.

Would you believe that riots afflicted a developed economy like Singapore in late December[17]?

So what the report didn’t say was that the untoward political repercussions from Singapore and Hong Kong’s property bubbles would have been inherited by the Philippines. But that’s if the housing boom transmission persists.

The good news is that rising bond yields of 10 year treasuries of both in Singapore and Hong Kong will most likely stymie any foreign demand for Philippine properties for speculative purposes. So this should temper any political ramifications from massive inflow of foreign money on domestic properties. But this will be bad news for developers and for stock market investors who bought into the “debt is prosperity” spin.

And as I previously noted the property bubble will induce a change in the composition of ownership[18]

…the ongoing leveraging by players in the property sector whom has access to the banking system may be acquiring properties from the 68% of households and selling these projects to the same high end sector whom have been speculating both in stocks and in properties

As events in Singapore reveal, property bubbles has nasty political consequences.

[1] See Should Your Housemaid Invest In The Stock Market? September 5, 2010

[2] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff This Time is Different Princeton Press

[3] Mises Wiki Money and banking in Ancient Rome

[5] John P. Hussman Topping Patterns and the Proper Cause for Optimism, Hussman Funds, February 17, 2014

[6] Interaksyon.com Who's afraid of interest rate spike? Not Ayala Land, as it eyes sale of more debt in 2014, February 14, 2014

[7] Wikipedia.org Dunning–Kruger effect

[8] See Philippine Overseas Workers Help Fuel Philippine Property Bubble June 14, 2012

[9] Wikipedia.org Veblen Goods

[10] ABS-CBNNews.com Why foreigners are snapping up properties in PH June 5, 2013

[11] See Philippine Economy: The Unseen Factors behind the “Doing Business” improvements October 30, 2013

[12] See Lessons from Singapore’s Central Bank: Central Banks are Vulnerable to Bankruptcies September 4, 2013

[13] See Singapore’s Gradualist Descent to the Welfare State August 12, 2012

[14] See Singapore’s Gradualist Descent to the Welfare State 2: The Rise of “Consultative Government” January 28, 2013

[15] See How Inflationism Spurred Singapore’s Labor Protectionism September 24, 2013

[16] Wall Street Journal Singapore Ups Sin Taxes Amid Higher Social Spending February 22, 2014

[17] See How Inflationism Propagated Singapore’s Riots December 10, 2013

[18] See Cracks in the Philippine Property Bubble? October 17, 2013