Right now, the FOMC has “a tiger by its tail” - it has lost control of monetary policy. The Fed can’t stop buying assets because interest rates will rise and choke the recovery. In short, today’s decision not to taper was driven by unimpressive economic data, the fear of a 3% yield on the 10 year Treasury and gridlock in Washington. If the economy cannot handle a 3% yield on the 10 year, then the S&P 500 should not be north of 1700. It is remarkable that the equity market continued to buy into easy money over economic growth. QE3 has been ongoing for nearly a year and the economy is not strong enough to ease off the accelerator (forget about applying the brake). Simultaneously, the S&P 500 is up 21% year to date and the average share gain in the index is over 25%. Maybe today’s action will turn out to be short covering, but if it was not then paying continually higher prices for equities in a potentially weakening economy is a very dangerous proposition. Mike O'Rourke at JonesTrading

How promises to extend credit easing (inflationist) policies can change the complexion of the game in just one week.

Spiking the Punchbowl Party, Negative Rates

In a classic Pavlovian response to the intense fears in May-June where central bank policies led by the US Federal Reserve would have the “punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up”[1], to borrow the quote from a speech of the 9th and longest serving US Federal Reserve chairman William McChesney Martin[2], retaining the “punch bowl” electrified the markets across the oceans.

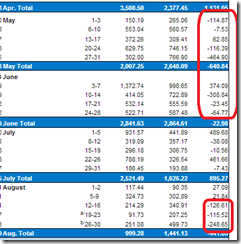

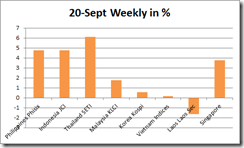

Badly beaten ASEAN market made a striking comeback this week.

A week back, sentiment rotation from falling global bond and commodity markets have begun to spur a shift of the rabid speculative hunt for yields towards equities. This has been justified by discounting the impact from the FED’s supposed taper

Yet this week’s dual events of the Larry Summer’s controversial withdrawal[3] from the candidacy of the US Federal Reserve chairmanship and the FED’s stiffing of the almost unanimous expectations of a pullback on central bank stimulus which proved to be the icing on the cake that spiked this week’s punch bowl party.

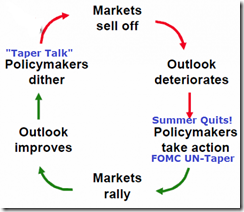

The above highlights much of how financial markets have been hostaged to policy steroids

The markets apparently saw Larry Summers as a “hawk” and a threat to the punch bowl party. This is in contrast to the current the Fed’s Vice Chairwoman Janet Yellen who has been seen as even more a “dove” than the outgoing incumbent Chairman Ben Bernanke.

Ms. Yellen, according to celebrated Swiss contrarian analyst and fund manager Dr. Marc Faber[4], will make Dr. Bernanke “look like a hawk”, because the former subscribed to negative interest rates.

Instead of the banks paying depositors, in negative rates, it is the reverse; depositors who pay the banks. And as likewise as analyst Gerard Jackson noted[5] “It is a situation in which the buyer of treasuries pays the government interest for the privilege of having loaned it money; a state of affairs in which a person's real savings are being continuously reduced”. In short, creditors will pay borrowers interest rates. This puts the credit system upside down.

If savers today are being punished under zero bound rates, negative rates will likely worsen such conditions. In a world where only spending drives the economy, ivory tower theorists mistakenly assume that savings will be forced into “spending” in the economy.

And Wall Street loves this because they presuppose that this will magnify the transfer or subsidies that they have been benefiting at the expense of the Main Street. In the real world, money that goes into speculating stocks represents as foregone opportunities for productive investments.

While the amplification of Wall Street subsidies may be the case, this may also prompt for an upside spiral of price inflation.

But on the other hand, if creditors (savers) will be compelled to pay debtors interest rates, assuming that under normal circumstances interest rates incorporate premium for taking on credit risk which will be reversed by edict, then why will creditors even lend at all? Why would depositors pay banks when they can keep money under the mattress? Or simply, why lend at all?

Denmark has adapted a negative deposit rate for the banking system in July of 2012[6] But this has not been meant to encourage spending but as a form of capital controls, viz prevent influx.

While the Danish central bank claims that this has been a policy success story, indeed capital flows have declined, the other consequence has been a sharp drop in net interest income (lowest in 5 years[7]) which has been due to the marked contraction in loans extended to the private sector.

Economic wide, the Danish negative rates has been a drag on money aggregates (M3), sustained “spending” retrenchment as shown by retail sales (monthly and yearly) and a growth recession based on quarter and annualized rates. So instead of inflation, in Denmark’s case it has been disinflation.

The problem is that once the US assimilates such policies, such will likely be adapted or imported by their global counterparts. The European Central Bank has already been considering such policies[8] last May.

The Denmark episode may or may not be replicated elsewhere. The point is that such adventurous policies run a high risk of unintended consequences.

The Fed’s UN-Taper: Spooked or Deliberately Designed?

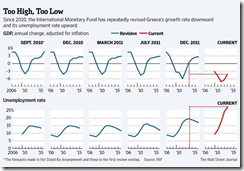

The consensus has declared that the US Federal Reserve has been “spooked”[9] by the bond vigilantes as for the reason for withholding the taper.

They can’t be blamed, the FOMC’s statement underscored such concerns, “mortgage rates have risen further and fiscal policy is restraining economic growth” and “but the tightening of financial conditions observed in recent months, if sustained, could slow the pace of improvement in the economy and labor market”[10]

However, I find it bizarre how stock market bulls entirely dismiss or ignore the impact of interest rates when the Fed authorities themselves appear to have been revoltingly terrified by the bond vigilantes.

But if the FED has been petrified by the bond vigilantes then this means that they likewise seem to recognize of the fragility of whatever growth the economy has been experiencing. In other words they have been sceptical of the economy’s underlying strength.

Some economic experts have even been aghast at the supposed loss of credibility by the US Federal Reserve’s[11] non transparent communications.

But I have a different view. I have always been in doubt on what I see as a poker bluff by the FED on supposed exit or taper strategies since 2010, for four reasons.

1. The US government directly benefits from the current easing environment. Credit easing represents a subsidy to government liabilities via artificially repressed interest rates. In addition, the current inflationary boom has led to increases in tax revenues. Both of these encourage the government to spend more.

As I previously wrote[12],

Given the entrenched dependency relationship by the mortgage markets and by the US government on the US Federal Reserve, the Fed’s QE program can be interpreted as a quasi-fiscal policy whose major beneficiaries have been the political class and the banking class. Thus, there will be little incentives for FED officials to downsize the FED’s actions, unless forced upon by the markets. Since politicians are key beneficiaries from such programs, Fed officials will be subject to political pressures.

This is why I think the “taper talk” represents just one of the FED’s serial poker bluffs.

2. The second related reason is that by elevating asset prices, such policies alleviates on the hidden impairments in the balance sheets of the banking and financial system. The banking system function as cartel agents to the US Federal Reserve, which supervise, control and provides relative guarantees on select elite members. The banking system also acts as financing agent for the US government via distribution and sale of US treasuries, and holding of government’s debt papers as part of their reserves.

For instance the reserves held by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporations (FDIC) are at only $37.9 billion, even when it insures $5.25 trillion of ‘insurable deposits’ held in the US banking system or about .7% of bank deposits. According to Sovereign Man’s Simon Black[13], the FDIC names 553 ‘problem’ banks which control nearly $200 billion in assets or about 5 times the size of their reserve fund.

In short should falling asset markets ripple across the banking sector, the FDIC would need to tap on the US treasury.

Essentially the UN-taper seem to have been designed to burn short sellers with particular focus on the bond vigilantes, where the latter may impact the balance sheets of the banking system.

3. Credit easing policies have been underpinned by the philosophical ideology that wages war against interest rates via the “euthanasia of the rentier[14]”. Central bankers desire to abolish what they see as the oppressive nature of the “scarcity-value of capital” by perpetuating credit expansion. So zero bound rates will be always be the policy preference unless forced upon by market actions in response to the real world dynamic of “scarcity-value of capital”

4. In the supposed May taper, where the markets reacted or recoiled with vehemence, the markets selectively focused on the taper aspect “moderate the monthly pace” even when the FED explicitly noted that “our policy is in no way predetermined” and even propounded of more easing[15].

This dramatic volatility from the May “taper talk” even compelled Fed chair Dr. Ben Bernanke to explicitly say “I don't think the Fed can get interest rates up very much, because the economy is weak, inflation rates are low. If we were to tighten policy, the economy would tank”[16]

In other words, the taper option functioned as a face saving valve in case the rampaging bond vigilantes would force their hand.

For me Dr. Bernanke’s calling of the Poker “taper” Bluff has been part of the tactic.

The bond vigilantes have gone beyond the Fed’s assumed control over them. And since the Fed construes that the rising yields has been built around the expectations of the Fed’s pullback on monetary accommodation, what has been seen a Fed “spook” for the mainstream may have really been a desperate ALL IN ante “surprise strike” gambit against the bond vigilantes. The Un-taper was the Pearl Harbor equivalent of Dr. Bernanke and company against the bond vigilantes.

The question now is if the actions in the yield curve have indeed been a function of perceived “tapering”. If yes, then given the extended UN-taper option now on the table, bond yields will come down and risk assets may continue to rise. But if not, or if yields continue to ascend in the coming days that may short circuit the risk ON environment, then this may force the FED to consider the nuclear option: bigger purchases.

But of course there have been technical inhibitions that may force the Fed to taper.

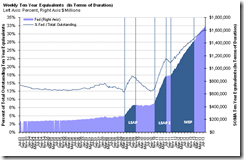

With shrinking budget deficits, meaning lesser treasury issuance and with the FED now holding “$1.678 trillion in ten year equivalents, or 31.89% as of August 30th total according to Zero Hedge[17], the Fed’s size in bond markets have been reducing availability of collateral. Reduced supply of treasuries, which function as vital components of banking reserves will only amplify volatility.

The Fed’s policies are having far wider unintended effects on the bond markets.

Should the Fed consider more purchases it may expand to cover other instruments.

The Fed has Transformed Financial Markets to a Giant Casino

While targeting the bond vigilantes, the FED’s UN-taper has broader repercussions; this served as an implied bailout to emerging markets and Asia.

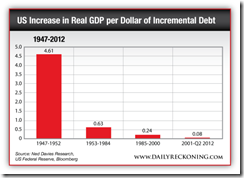

Mainstream analysts have been quick to grab this week major upside move as an opportunity to claim that the Fed’s actions vastly reduced risks to the global economy. They conclude without explaining why despite the huge (more than double) expansion of assets by the major central banks since 2008 which now accounts for about 12-13% of the global GDP, economic growth remains highly brittle.

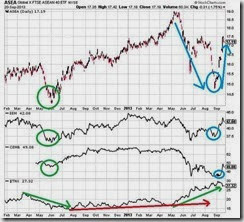

They even point out that current conditions seem like a replay of the May 2012 stock market selloff (green ellipses) where emerging markets stocks (EEM) and bonds (CEMB Emerging Market Corporate bonds) as well as ASEAN stocks (ASEA) eventually climbed.

They forgot to say that the selloff in May 2012 had been one of a China slowdown and signs of market stress from the dithering of the Fed’s on QE 3.0[18]. Importantly markets sold off as yields of 10 year US notes trended to its record bottom low in July.

Today has been immensely a different story from 2012. UST yields have crept higher since June 2012 (red trend line). The effects on UST yield by QE 3.0 a year back (September 13, 2012) had been a short one: 3 months. This means in spite of the program to depress bond yields, bond yields moved significantly higher.

The upward ascent accelerated a month after Abenomics was launched and days prior the sensational taper talk. Nonetheless, media and authorities believe that rising yields have been a consequence of a purported Fed slowdown and from ‘economic growth’

What has been seen as economic growth by the mainstream has really been an inflationary boom which indeed contributes to higher yields. Yet the consensus ignores that rising yields may also imply of diminishing real savings and deepening capital consumption via implicit revulsion towards more easing policies that has only been fueling an acute speculative frenzy on asset markets driving the world deeper into debt.

As analyst Doug Noland at the Credit Bubble Bulletin notes[19]

Last week set an all-time weekly record for corporate debt issuance. The year is on track for record junk bond issuance and on near-record pace for overall corporate debt issuance. At 350 bps, junk bond spreads are near 5-year lows (5-yr avg. 655bps). At about 70 bps, investment grade Credit spreads closed Thursday at the lowest level since 2007 (5-yr avg. 114bps). It's a huge year for M&A. And with the return of “cov-lite” and abundant cheap finance for leveraged lending generally, U.S. corporate debt markets are screaming the opposite of tightening.

And such “all-time weekly record for corporate debt issuance” has coincided with the equity funds posting the “second largest weekly inflow since at least 2000” according to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch as quoted by the Zero Hedge[20]. The year 2000 alluded to signified as the pinnacle of the dot.com mania.

How will rising stock prices reduce risks in the real economy?

In the case of India, the Reserve Bank of India led by Chicago School, former IMF chief and supposedly a free market economist Raghuram Rajan sent a shocker to the consensus by his inaugural policy of raising repurchase rate rates by a quarter point to 7.5, which is all not bad.

However Mr. Rajan contradicts this move by relaxing liquidity curbs by “cutting the marginal standing facility rate to 9.5 percent from 10.25 percent and lowering the daily balance requirement for the cash reserve ratio to 95 percent from 99 percent, effective Sept. 21. The bank rate was reduced to 9.5 percent from 10.25 percent.”[21]

So the left hand tightens while the right hand eases.

Sure India’s stocks as indicated by the Sensex have broken into the year’s highs and is at 2011 levels, but it remains to be seen how much of the record highs have factored in the risks from such policies and how of the current price levels have been from the Summer-Fed UN-taper mania.

As one would note in the Sensex or from ASEAN-Emerging Markets stocks, current market actions have been sharply volatile in both directions. And volatility in itself poses as a big risks. Financial markets have become a giant casino.

QE Help Produce Boom-Bust Cycles and is a Driver of Inequality

It is misguided to believe that QEternity extrapolates as an antidote to an economic recession or depression.

The reality is Quantitative Easing extrapolates to discoordination or the skewing of consumption and production activities which leads to massive misallocation of capital or “malinvestments”. QE also translates to grotesque mispricing of securities and maladjusted price levels in the economy benefiting the first recipients of credit expansion.

And all these have been financed by a monumental pile up on debt and equally a loss of purchasing power of currencies.

Eventually such imbalances will be powerful enough to overwhelm whatever interventions made to prevent them from happening, specifically once real savings or capital has been depleted.

As the great Austrian Ludwig von Mises warned[22]

But the boom cannot continue indefinitely. There are two alternatives. Either the banks continue the credit expansion without restriction and thus cause constantly mounting price increases and an ever-growing orgy of speculation, which, as in all other cases of unlimited inflation, ends in a “crack-up boom” and in a collapse of the money and credit system. Or the banks stop before this point is reached, voluntarily renounce further credit expansion and thus bring about the crisis. The depression follows in both instances.

QE also means a massive redistribution of wealth.

Rising stock markets have embodied such policy induced inequality.

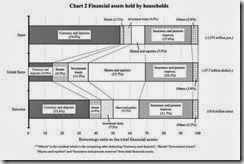

US households have the biggest exposure on stocks with 33.7% share of total financial assets according to the Bank of Japan[23].

In Japan, only 7.9% of financial assets have been allocated to equities. This means that Abenomics will crater Japan’s households whose biggest assets have been currency and deposits. The Japanese may pump up a stock or property bubble or send their money overseas.

In the Eurozone, stocks constitute only 15.2% of household financial assets.

The above figures assume that each household has exposure in stocks. But not every household has exposure on stocks.

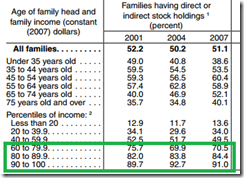

In the US for instance, while 51.1% of families have direct or indirect holdings on the stock markets as of 2007[24], a significant share of stock ownership have been in the upper ranges of the income bracket (green rectangle).

Since the distribution of ownership of stocks has been tilted towards the high income groups, FED policies supporting the asset markets only drives a bigger wedge between the high income relative to the lower income groups.

This is essentially the same elsewhere.

In the Philippines, according to the PSE in 2012 there have been only 525,850 accounts[25] of which 96.4% has been retail investors while 3.6% has been institutional accounts.

And of the total, 98.5% accounted for as domestic investors while foreigners constituted 1.5%.

Amazingly the 2012 data represents less than 1% (.54% to be exact) of the 96.71 million (2012 estimates) Philippine population.

Meanwhile online participants comprised 78,216 or 14.9%[26].

In 2007 the PSE survey reported only 430,681 accounts[27]. This means that the current stock market boom has only added 22.1% of new participants or 4.07% CAGR over the past 5 years.

The media’s highly rated boom hasn’t been enough to motivate much of the public to partake of FED-BSP manna.

One may add that some individuals may have multiple accounts, or members of the one family may all have accounts. This means that the raw data doesn’t indicate how many households or families have stock market exposure. Under this perspective, the penetration figures are likely to be even smaller.

This also means that in spite of the headline hugging populist boom, given the sluggish growth of ‘new’ stock market participants most of pumping up of the bull market activities have likely emanated from recycling of funds or increased use of leverage to accentuate returns or the deepening role of ‘fickle’ foreign funds. I am sceptical that the major stockholders will add to their holdings. They are likely to sell more via secondary IPOs, preferred shares, etc…

And this means that for the domestic equity market to continue with its bull market path would mean intensifying use of leverage for existing domestic participants and or greater participation from foreigners. That’s unless the lacklustre growth in new participants reverses and improves significantly.

And it is surprising to know that with about half of the daily volume traded in the PSE coming from foreigners, much of this volume comes from the elite (1.5% share) of mostly foreign funds.

So who benefits from rising stock markets?

As pointed out in the past[28], the domestic elite families who control 83% of the market cap as of 2011.

The other beneficiary has been foreign money which accounts for the 16% and the residual morsel recipients to the retail participants like me.

So the BSP’s zero bound rates, whose credit fuelled boom inflates on statistical growth figures, likewise drives the inequality chasm between the “haves” and the “havenots” via shifting of resources from Mang Pedro and Juan to the Philippine version of Wall Street.

Interviewed by CNBC after the Fed’s surprise decision to UN-Taper, billionaire hedge fund manager Stanley Druckenmiller, founder of Duquesne Capital commented[29]

This is fantastic for every rich person…This is the biggest redistribution of wealth from the middle class and the poor to the rich ever.

Such stealth transfer of wealth enabled and facilitated by central bank policies are not only economically unsustainable, they are reprehensively immoral.

[1] Wm. McC. .Martin, Jr . Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System before the New York Group of the Investment Bankers Association of America Punch Bowl Speech October 19, 1955 Fraser St. Louis Federal Reserve

[27] Philippine Stock Exchange, Less than half of 1% of Filipinos invest in stock market, PSE study confirms 16 June 2008 News Release Refer to: Joel Gaborni -- 688-7583 Nina Bocalan-Zabella – 688-7582 (no available link)

![[clip_image009%255B3%255D.png]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-kfbo0Uaxtyc/UmQXuMj8IqI/AAAAAAAAXXw/8jxf9KFMp1A/s1600/clip_image009%25255B3%25255D.png)