The IMF’s advice to central bankers is an example why we can expect central bankers to keep blowing asset bubbles.

That’s of course until bubbles pop by their own weight, or until the stagflation menace emerges or a combo of both.

But stagflation has been absent based in the econometric papers of the IMF, that’s according to the Bloomberg:

Monetary stimulus deployed by advanced countries to spur growth is unlikely to stoke inflation as long as central banks remain free of outside influence to react to challenges, according to a study by the International Monetary Fund.

In a chapter of its World Economic Outlook released today, the Washington-based IMF said that inflation has become less responsive to swings in unemployment than in the past. Inflation expectations have also become less volatile, according to the report.

“As long as inflation expectations remain firmly anchored, fears about high inflation should not prevent monetary authorities from pursuing highly accommodative monetary policy,” IMF economists wrote in the chapter called “The dog that didn’t bark: Has inflation been muzzled or was it just sleeping?”

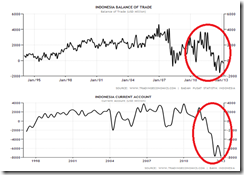

Considering the distinctive political-economic structure of each nations, such pursuit of bubble policies will translate to varying impacts on specific markets and economies. For instance, emerging markets are likely to be more vulnerable to price inflation.

And by simple redefinition and measurement of inflation as based on econometric models and statistics, the IMF has given the green light for central bankers do more.

This also means that the IMF has prescribed to central bankers to throw fuel on the inflation fire.

Based on mainstream’s twisted definition of inflation, such as being predicated on demand and supply “shocks”, hyperinflation ceases to exist.

Interestingly too the IMF hardly see current policies as having “compromised” central bank independence.

Again from the same article:

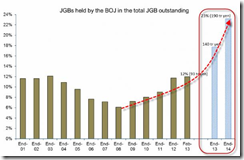

The BOJ’s new policy “is something that we hope will lift inflation durably into positive territory, which would help the economy,” said Jorg Decressin, deputy director of the IMF’s research department. “We see in no way the operational independence of the BOJ compromised at all.”

This is a rather absurd claim. When central banks buy government debt, they effectively encroach into the realm of fiscal policies.

Instead of voters determining the dimensions of fiscal policies via taxation, central bank financing of fiscal deficits motivates government profligacy that enhance systemic fragility through higher debts and the risks of price inflation (stagflation) or even hyperinflation.

Historically, and across the world, the primary driver of inflation has always been expansion in unproductive government spending (think of Germany paying striking workers in the early 1920s, or the massive increase in Federal spending in the 1960s that resulted in large deficits and eventually inflation in the 1970s). But unproductive fiscal policies are long-run inflationary regardless of how they are financed, because they distort the tradeoff between growing government liabilities and scarce goods and services.

For instance, Japan’s government will increasingly become dependent on the Bank of Japan via Kuroda’s “shock and awe” Abenomics policies. This makes Japan vulnerable to a debt or a currency crisis.

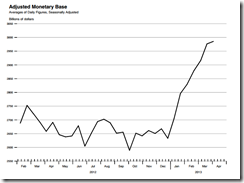

And recent interventions on the fiscal space by central banks of developed economies essentially reveals of the closely intertwined relationship between governments and central banks. (charts above from Zero Hedge)

This only validates the hypothesis of the Austrian school of economics that the fundamental role played by the central banks has been to support the government (welfare-warfare state) and the cartelized crony banks, which essentially means that central bank independence is a myth.

The Central Bank has always had two major roles: (1) to help finance the government's deficit; and (2) to cartelize the private commercial banks in the country, so as to help remove the two great market limits on their expansion of credit, on their propensity to counterfeit: a possible loss of confidence leading to bank runs; and the loss of reserves should any one bank expand its own credit. For cartels on the market, even if they are to each firm's advantage, are very difficult to sustain unless government enforces the cartel. In the area of fractional-reserve banking, the Central Bank can assist cartelization by removing or alleviating these two basic free-market limits on banks' inflationary expansion credit

Yet here is the IMF’s prescription for more bubble blowing, from the same article:

“The dog did not bark because the combination of anchored expectations and credible central banks has made inflation move much more slowly than caricatures from the 1970s might suggest - - inflation has been muzzled,” the IMF staff wrote. “And, provided central banks remain free to respond appropriately, the dog is likely to remain so.”

As I explained before, inflationism represents a political process employed by governments to meet political goals. Inflationism, which is an integral part of financial repression, signify the means (monetary) to an end (usually fiscal objectives). And when governments become entirely dependent on money printing from central banks, hyperinflations occur.

Just because money printing today has not posed as substantial risks to price inflation, this doesn’t mean such risks won’t ever occur.

And that the current low inflation environment basically implies "free lunch" for central banks.

Price controls, market manipulations (via central bank), the Fed’s Interest rate on reserves (IOR) and even productivity issues have also contributed significantly to subdue price inflation over interim.

And again since monetary inflation represents a process, such take time to unfold via different stages, which is why price inflation tend to occur with suddenness to become a significant threat.

IMF’s reckless advocacy of bubble policies will have nasty consequences for the world.

The IMF experts or bureaucrats, who are paid tax free and are tax consumers, hardly realize such blight will affect them too.

Yet should a crisis of a global dimension emerge, and where a chain of defaults by governments on their liabilities (such may include developed economies, BRICs, Asia and elsewhere), their privileges, if not their existence, will likewise be jeopardized, as governments retrench or have their respective budgets severely slashed or faced with real "austerity".

Let me venture a guess, such scenarios haven’t been captured by the IMF's econometric models.

When the late Margaret Thatcher warned that "the problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people's money [to spend]", this applies to multilateral institutions too.