Desperate debt burdened governments will resort to the brazen confiscation of the savings of their constituents.

In the case of Poland almost half of private pensions have been nationalized.

Notes the Zero Hedge (bold original)

By way of background, Poland has a hybrid pension system: as Reuters explains, mandatory contributions are made into both the state pension vehicle, known as ZUS, and the private funds, which are collectively known by the Polish acronym OFE. Bonds make up roughly half the private funds' portfolios, with the rest company stocks.And while a change to state-pension funds was long awaited - an overhaul if you will - nobody expected that this would entail a literal pillage of private sector assets.On Wednesday, Prime Minister Donald Tusk said private funds within the state-guaranteed system would have their bond holdings transferred to a state pension vehicle, but keep their equity holdings. The funds would effectively be left with only the equities portions of their assets, even this would be depleted, and there will be uncertainty about the number of new savers joining.But why is Poland engaging in behavior that will ultimately be disastrous to future capital allocation in non-public pension funds (the type that can at least on paper generate some returns as opposed to "public" funds which are guaranteed to lose)? After all, this is a last ditch step which no rational person would engage in unless there were no other option. Simple: there were no other option, and the driver is the same reason the world everywhere else is broke too - too much debt.By shifting some assets from the private funds into ZUS, the government can book those assets on the state balance sheet to offset public debt, giving it more scope to borrow and spend. Finance Minister Jacek Rostowski said the changes will reduce public debt by about eight percent of GDP. This in turn, he said, would allow the lowering of two thresholds that deter the government from allowing debt to raise over 50 percent, and then 55 percent, of GDP. Public debt last year stood at 52.7 percent of GDP, according to the government's own calculations.To summarize:1. Government has too much debt to issue more debt2. Government nationalizes private pension funds making their debt holdings an "asset" and commingles with other public assets

3. New confiscated assets net out sovereign debt liability, lowering the debt/GDP ratio4. Debt/GDP drops below threshold, government can issue more sovereign debt

The seizure of private sector savings to lower debt levels only whets government’s appetite to go into a spending binge.

The Polish government’s spending extravaganza as seen via chronic budget deficits

Nationalization of pensions funds means that the Polish government sees a growing risk of diminished access to external financing as external debt has been swelling to finance lavish government spending habits.

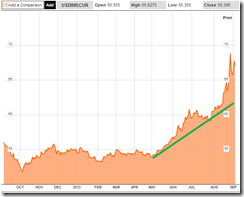

The actions of the Polish government appear to have slammed her equity markets as seen via the WIG benchmark.

And with it, Polish bonds has been sold off (along with the world)

Actions by Polish policymakers may aggravate the dour sentiment on emerging markets.

As Reuter’s analyst Sujata Rao at Global Investing observed: (bold mine)

If the backdrop for global emerging markets (GEM) were not already challenging enough, there are, these days, some authorities that step in and try to make things even worse, writes Societe Generale strategist Benoit Anne. He speaks of course of Poland, where the government this week announced plans to transfer 121 billion zlotys ($36.99 billion) in bonds held by private pension funds to the state and subsequently cancel them. The move, aimed at cutting public debt by 8 percentage points, led to a 5 percent crash yesterday on the Warsaw stock exchange, while 10-year bond yields have spiralled almost 50 basis points since the start of the week. So Poland, which had escaped the worst of the emerging markets sell-off so far, has now joined in.But worse is probably to come. Liquidity on Polish stock and bond markets will certainly take a hit —the reform removes a fifth of the outstanding government debt. That drop will decrease the weights of Polish bonds in popular global indices, in turn reducing demand for the debt from foreign investors benchmarked to those indices. Citi’s World Government Bond Index, for instance, has around $2 trillion benchmarked to it and contains only five emerging economies. That includes Poland whose weight of 0.55 percent assumes roughly $11 billion is invested it in by funds hugging the benchmark.

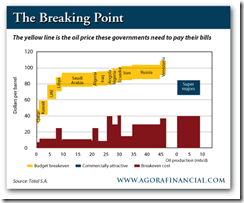

As the US dollar liquidity is being drained off the world, governments will become increasingly exposed on their dependence on debt, and subsequently on their debt based economies.

Such dynamic are presently being ventilated mainly via the currency markets where many emerging markets including the ASEAN region have been facing a currency storm.

Nonetheless, pension funds have increasingly become targets for government’s financial repression as in the case of Argentina and Spain.

Pension funds have also transformed into tools for market interventions in order to support political objectives such as in the Philippines.

And the seeming political trend in response to the US dollar scarcity has been knee jerk reactions to indulge in more direct and harsher financial repression or savings confiscation measures.

Hardly a positive sign.