In this issue:

Phisix: In 2009, the BSP Engineered a Crucial Pivot to a Bubble Economy

-Has Mr. Bastiat’s principles come to haunt the BSP?

-The Fallacy of Aggregate Demand

-The Stages of Inflation

-The 2009 Pivot Towards the Domestic Demand Bubble

-Costs are NOT Benefits

-Bastiat’s Unheeded Warning for the BSP

-Why a Rotation to Emerging Market Stocks is Unlikely

-Phisix: Market Internals Point to a Steep Correction

Phisix: In 2009, the BSP Engineered a Crucial Pivot to a Bubble Economy

Two of my neighboring “carinderias” or informal retail food (eatery) outlets raised viand prices by 14% this week.

Has Mr. Bastiat’s Principles come to haunt the BSP?

In April 2009, in a speech before the Australian-New Zealand Chamber of Commerce, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas governor Mr Amando M Tetangco, Jr concluded[1]

Frederic Bastiat, a 19th century French economic journalist, once said, “there is only one difference between a bad economist and a good economist: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account the effects that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen”.It may be difficult to perfectly foresee things but this should not discourage us from trying. Thus, I encourage all of us in this venue to remain positive, yet vigilant for any circumstances that could come our way. The BSP, for its part, will remain committed and continue to put forth monetary policy actions and banking reforms that will allow our economy to withstand the road blocks comprising panics, crises and other changes in the horizon.

The good governor had framed Mr. Bastiat in the confused context of merely about foreseeing things or making predictions. But this was not the intended message of Mr. Bastiat. Mr. Bastiat wrote about the importance of the subsequent order effects or the intertemporal tradeoffs (short term versus long term) of political actions to the real economy.

Let me expand the truncated quote of Mr. Bastiat:

Yet this difference is tremendous; for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. Whence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good that will be followed by a great evil to come, while the good economist pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present evil.

The excerpt came from the book “That Which is Seen and That Which is Not Seen”[2]. Bastiat’s book has essentially been about exposing the unseen or unintended consequences from the centralization—via the politicization—of the economy, particularly through seeing good news in destruction (broken window fallacy), demilitarization (disbanding of troops), public work spending, taxes and most importantly credit (inflationism) among the many other forms political interventionism also tackled in the book.

You see, the great Claude Frédéric Bastiat was more than just a journalist, a political economist and a legislator; he championed private property, free markets, and limited government and whose ideas have functioned as one of the pillars for the Austrian school of economics[3].

In other words, the essence of the book whence the BSP chief cited Mr. Bastiat has been diametrically opposite to the principles of central planning as advocated by the former. Bastiat was not for “monetary policy actions”

Has Mr. Bastiat’s principles have come to haunt the BSP?

The Fallacy of Aggregate Demand

Strains on the BSP have become increasingly evident.

Despite the melt-UP in the peso this week, the BSP has once again hinted at a supposed “further tightening”. The BSP governor was quoted, “we continue to be mindful of strong domestic liquidity and credit growth that could heighten financial stability risks…[This] was an important consideration for the preemptive move of raising [the reserve requirement] at our last meeting.”[4]

The fact that the BSP chief had to go to the public again (for the second time in less than 3 weeks) to signal “tightening” is a manifestation of political pressures on BSP monetary policies. The BSP have been a promoter of zero bound rates since 2009 (see below).

In addition, March data on Philippine forex reserves or Gross International Reserves revealed a modest decline of $ 700 million ($.7 billion) reportedly partly due to “foreign exchange operations of the BSP”[5]. Since the Peso meltdown came during the third week of March, this has possibly muted on the scale of operations by the BSP.

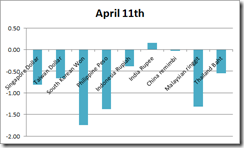

The Peso has been this week’s biggest gainer. This has reversed all the previous declines. This comes as most Asian currencies rallied strongly against the US dollar. Given Friday’s close, the Peso now trades modestly up for the year.

Of course as I mentioned last week, aside mainly from intervention, another factor that would support the peso over the interim is the RISK ON environment. This volatile RISK ON environment supposedly comes from what media claims as ‘rotational’ dynamic as international money managers switch out of technology funds and stampede into Emerging Markets funds allegedly out of valuation reasons. [This I will discuss later]

Yet the decline in March forex reserves validates my suspicion that “the BSP may have used anew forex reserves to defend the peso.”[6] And as I have repeatedly been saying, the BSP has adamantly refrained from using the interest rate channel or the self-imposed banking sector limits to the property sector and instead relies on superficial actions of marginally raising reserve requirements, currency interventions and jawboning via signaling channel or information dissemination management.

In terms of communications management, following the official raising of bank reserve ratios 2 weeks back, the BSP announced “lower” inflation for March a week ago. This week the Philippine government released economic data purportedly showing a strong 24.4% jump in exports. Then the BSP chief went on air to hint at “tightening”. Such are intensifying signs that the peso is being “managed” by the BSP.

In other words, aside from the providence temporarily provided by the region’s strong currency vis-à-vis the weak dollar trade, as I recently wrote, any improvement in the peso will have the BSP’s fingerprints on them[7].

I noted that BSP has been a promoter of zero bound rates since 2009. I have recently discovered that this bubble commenced in 2009, after the BSP chief exhorted for a shift in policies in order to promote ‘domestic demand’ via aggregate demand policies of low interest rates and fiscal spending.

From the Trade Union Congress of the Philippines[8]: (bold mine)

“There are views that Asia must boost domestic consumption and end its dependence on exports,” Tetangco said. “In the longer term the view is that Asian economies may need to look more at their own domestic economies as the engine of growth.”According to Tetangco, counter-cyclical support to aggregate demand in the form of expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, along with strong policy actions to ensure financial and corporate sector health could contribute to faster recovery.“Maintaining an expansionary monetary policy stance to the extent that the inflation outlook allows, could support market confidence and assure households and businesses that risks to macro-stability are being addressed decisively,” he said.

In a barter economy, exchanges are conducted through direct exchange of product/s or service/s without the use of the medium of exchange. Say for instance, a shoemaker will exchange an agreed number of his produce (shoe/s) with a baker for an agreed amount of the latter’s product/s (bread/s). In short, trade is simply an exchange of agreed outputs between two producers or service providers.

The problem with a barter system is in the matching of people’s wants and needs to encourage transactions. Such is called the ‘coincidence of wants’[9]. For example, during a given moment, a shoemaker wants to trade his shoes only with the farmer’s vegetables. But the farmer solely desires to trade his vegetables for the baker’s bread. On the other hand, the baker wants to exclusively trade his bread for shoes with the shoemaker. So the mismatch between the wants and needs of each producer becomes an obstacle (or high transaction costs) to the facilitation of exchange in a barter system.

The introduction of the money or an intermediary as medium of exchange solves this discrepancy by providing liquidity to the producers.

So what am I attempting to point out? All these shows that demand is a function of supply. Money is just a medium of exchange. And the purchasing power of money equals the extent of supply.

Example: If a person carrying a bag of N million of currency units (US dollar or Peso or Euro or etc…) due to an accident is stranded in a remote island inhabited by primitive tribes who lives on fish and coconuts and whose contact with the outside world is severely restricted, then the purchasing power of such currency unit (if accepted by the tribes at all) is only fish and coconuts.

We have seen the value of money in action recently during a supply shock brought about by Typhoon Yolanda in the hardest hit area of Tacloban City in Leyte. Despite the availability of money as I noted here[10]…

Trade or voluntary exchanges has been incapacitated for the simple reason of lack of access to basic goods (food, water, medicine) to fulfill physiological needs (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs).

And the lesson of money being…

The unfolding developments from the unfortunate Typhoon Yolanda tragedy represent a testament to the fundamental economic truism where money, in and of itself is not wealth, rather it is the purchasing power of money (or what money can buy) that reflects on wealth.

This brings us back to domestic aggregate demand based policies pushed and implemented by the BSP chief in 2009.

What the BSP chief effectively ordered was to inflate the system or to blow bubbles.

Yet in the knowledge that much of the Filipino consumers have little access to the formal banking system, credit inflation was tacitly designed to boost the supply side, who in their vast expansion programs, would add to the demand side that would boost revenues of the government and simultaneously indirectly and covertly divert the society’s resources towards subsidizing government spending via suppressed interest rates on sovereign liabilities

Credit creation and expansion to bubble industries has affected relative price levels and has distorted economic coordination of resources aside from altering the production process. This has become very conspicuous now.

Inflated profits from earlier credit creation and bigger capital expansions facilitated by greater bank lending provided a significant boost to consumer demand too. People within the bubble industries, as well as in the adjunct industries have more disposable income to buy consumption goods and spend on leisure activities. So alongside from OFW based remittances and income and profits from BPOs, disposable income from bubble industries artificially bolstered or padded revenues of retail outlets, hotels and many other consumer based products. This gave property developers, shopping mall and hotel operators and financial intermediaries of asset bubbles (financial assets and property related) the impression of the boundless potentials of the Filipino consumers.

But of course, contra the mainstream, nothing is ever aggregate. Even companies from within the industries benefiting from the bubble do not benefit evenly. Some benefit more than the others. Some clues of such dynamics can be seen from the variance in the compounded annualized growth rates of earnings per share and book value of the 30 member Phisix components.

Moreover given the predisposition by the banking system and the credit markets to lend to big named and politically connected borrowers, such entails that the distribution of benefits and risks tend to be concentrated. The corporate bond market is a shining example of this, as I earlier noted “because of the small size of the corporate bond market, the top 10 share in terms of % to the total is at 90.8%. Said differently, the benefits and risks of Philippine corporate bonds have been concentrated to these top 10 issuers.[11]”

You see the farther the distance a firm or an enterprise is to the epicenter of the credit inflation, the lesser the benefits from the Cantillon spillover effects. So essentially, for the Philippines, the informal economy would signify as the last link in the credit process. Yet as farthest in the monetary economic link, they are to be the hardest hit by the effects of BSP’s bubble policies.

For the informal sector to raise prices is a sign of trouble. For instance, informal sector eateries (or even “sari sari stores” mini convenience stores) operate in highly competitive markets where the typical business model have been based on slim margins and are highly dependent on the scale of volume. Since most of their consumers are from the minimum wage levels, such consumers are heavily sensitive (elastic) to price changes given their limited purchasing power. So raising prices would signify as a drastic recourse in response to changes in prices of entrepreneurial operations. Yet an escalation of price inflation will put many informal enterprises out of business.

And I pointed out last week, money from credit growth simply means additional purchasing power, which will be spent or allocated in the real economy. The temporary-short term increase in purchasing power in favor of select groups will impact prices and the distribution of goods and the production process over relative time frames. Thus additional money from credit growth from the fractional banking system marginalizes existing money which means a long term loss of real purchasing power. Yet despite government data, this process has now been intensifying

To make clear, whether inflated money stems from bank credit growth or from government monetizing spending via deficits, the effects will be the same. As the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises wrote, “Today the techniques for inflation are complicated by the fact that there is checkbook money. It involves another technique, but the result is the same. With the stroke of a pen, the government creates fiat money, thus increasing the quantity of money and credit”[12].

The difference will be from the source/s of risks. Since the 68% of the 30+% money supply growth comes from banking loans to the private sector then this means the immediate risks for the Philippines is one of bubble implosion from a credit fueled asset bubble.

Meanwhile the risks for countries like Argentina and Venezuela or the rest of the other nations that saw money growth at over 30+% in 2011 and or 2012 or in both years based on World Bank data—such as Sudan, Tajikstan, Myanmar, Malawi, Liberia, Iran, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Congo Republic, Belarus, Azerbaijan and Angola—has been mostly on hyperinflation or total bankruptcy. [As a snarky side remark, a very impressive lists of colleagues.]

Yet in 2012, Belarus recently suffered from hyperinflation[13]. Meanwhile, Myanmar property bubble[14] appears as being accommodated by the huge money supply increase.

The Stages of Inflation

Inflation in essence signifies a series of political actions whose effects on the marketplace can be identified as having 3 stages which vary in time periods.

The first stage is when consumer prices barely rise at all even if the rate of money supply growth significantly expands. That’s because most people think that price inflation will be transient. Therefore instead of spending, the people tend to save more money in anticipation of lower prices. [As a side note, this seems as the case in Japan today[15]]

Such action would imply an increase in social demand for money. The gestation period tends to be longest here. Yet this phase represents the sweet spot for the invisible transfer of resources from the society to the government. The great dean of Austrian economics Murray N. Rothbard explained[16],

The government obtains more real resources from the public than it had expected, since the public’s demand for these resources has declined

The second stage is when the public comes to realize that prices continue to rise, so they step up the rate of goods purchases. So the social demand for money falls. The rate of price increases now accelerates. They will rise to the proportion of rate of growth of the money supply. This would be the rigid quantity of money theory[17]. The second phase serves as a springboard to the third phase, thus has a very much shorter time frame. Argentina’s inflation seems as in the second stage.

The third and final stage will be when trust in the domestic currency continues to substantially erode. People will go into a panic buying spree in order to dispense of their currency in exchange for real goods. Here price inflation will far outpace money supply growth. This phase is known as the runaway or hyperinflation.

For the Philippines, if the 30+% money supply growth rate continues then we should expect a significant pick up in price inflation rates, no matter what the mainstream or official data says. This also shows that the Philippines may be in the basketball equivalent of the third quarter of the first stage of the inflation cycle.

Yet all the financial price “management” measures by the BSP (applied to the peso and to bonds) will eventually fail for they continue to deal with the symptoms rather addressing the root cause of the present imbalances.

Nonetheless given the propensity to attack the symptoms, it is not farfetched that the Executive Branch will join the BSP to impose populist ‘price control’ measures.

But should this be the case, then we should expect an aggravation of shortages. What will happen is that statistical price inflation will fall but the peso will also plunge. But if the peso will be controlled, then either we see the vaunted forex reserves decline significantly or that a foreign exchange black market will emerge.

The 2009 Pivot Towards the Domestic Demand Bubble

Importantly, as noted above it was in 2009 where the Philippines economy made a critical pivot towards a bubble economy. This has been a consequence of BSP’s bubble blowing policies aimed at refocusing to the economy towards domestic demand via aggregate demand policies.

Essentially Mr. Tetangco’s call to action for a shift in focus by sacrificing external trade in 2009 essentially validated my observation last week[18],

we shouldn’t expect material improvements in domestic export industry even amidst a weak peso environment due to substantial resources already committed by a large segment of the formal economy in the redirection of their efforts towards bubble blowing industries rather than to the production for exports. In short, current easy monetary policies have incented a shift in the Philippine economy’s production structure favoring bubble industries at the expense of external trade.

By politically choosing winners and losers through monetary policies, the BSP has fundamentally “crowded out” resources available to the export industry via transfers to the bubble sectors and to the government. Along with restrictive regulations, the weak peso will hardly pose as subsidy for exports as massive resources have already been sunk into future malinvested projects that will soon be exposed as unprofitable.

So while the Philippine government reported[19] a 24.4% spike in February 2014 export growth last week (see chart via this link), this only represents half of the real picture. Why? Because the supposed extraordinary growth came from a vastly depressed February 2013 export data (see chart here). In nominal terms, February 2014 data has even been below many of the monthly data for the 2nd and 3rd quarter of 2013. So the so-called ‘strong’ growth seems all been about framing and the contrast principle or compared to what?

This brings us back to the inner sanctum of the BSP’s fulcrum towards bubble policies.

Let us do some legwork on the recent data.

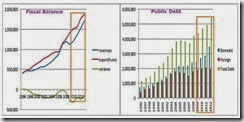

In 2013, Philippine government revenues grew by 11.8% year on year based on the data provided by the National Statistical Coordination Board (see left window). This rate is way above the CAGR of 8.07% over the past 17 years or from 1996-2012 and was obviously influenced by the half year 30+% money supply growth. Since the BSP reconfigured the nation’s economic structure, government revenues jumped by a CAGR 8.85% from 2009 until 2013. Again the latter has been skewed by the hefty increase in the 2013 data.

To reemphasize, this substantial growth in government revenues has largely been brought about by a boom in the mostly the bubble sectors of the formal economy due to bank credit inflation, as evident by the 30++% money supply rate growth, that has inflated revenues, income and earnings.

Meanwhile expenditures grew by only 5.8% in 2013. This has largely been below the 17 year CAGR (1996-2012) of 9.1%. Since 2009, the annualized growth rate has been slower than the earlier years at 5.75% or about the same rate as 2013. This has eased on the fiscal deficit which should signify as good news.

But media yammers about restrained government spending. A report insinuates that anti-corruption measures have diminished government spending in Asia (including the Philippines) therefore involuntary “austerity” comes at the cost of statistical growth[20]. For media anything that slows spending is bad. Such is an example of the Bastiat’s “seen” effect while at the same time discounting the “unseen” benefits of the diminished government spending.

And signs of “prudence” may just be jettisoned in 2014, as I previously noted[21],

The BIR, which accounts for 70% of the government’s total revenues, expects a 16.16% increase in her 2014 target. That’s because national government budget will expand by 13% to Php 2.265 trillion in 2014. So government spending will grow about twice the statistical economy….All these means that the incumbent government will have to increasingly rely on a sustained credit financed boom of assets in the formal economy in order to fund her fast expanding spendthrift appetite, as well as, to maintain zero bound rates or negative real rates (bluntly financial repression) to keep her debt burden manageable.

Now let us move on to debt (right window)

According to the data from Bureau of Treasury, Public debt (domestic and internal) in 2013 has grown by only 4.5% in 2013 as against the CAGR of 9.54% from 1996-2012. Since 2009, the total public debt has grown by only 5.3% compounded annualized. [note: not included is the government guaranteed debt]

And here is the beauty: the Philippine government has shifted the share of debt burden in 2009 which was at 44:56 in favor of domestic debt to 2013’s 34:66 share, again in favor of domestic debt. While public debt continued to grow modestly, the Philippine government deftly transferred the weightings significantly towards domestic debt (again from 56% in 2009 to 66% 2013) in order to optimize the capture of the subsidies provided by the Philippine society to the government from negative real rates—financial repression policies.

The statistician cum economic analyst will see this as good news. Yehey, great debt management they say! But if we apply the great Bastiat’s methodology of looking at the “unseen” long term consequence from current policies that have brought about the current benign “visible” effects, we will see a vastly different picture.

Costs are NOT Benefits

Well the above figures reveal to us that costs are not benefits.

What seems as prudent is in fact reckless. The principal cost to attain lower public debt has been to inflate a massive bubble. The current public debt levels have been low because the private sector debt levels, specifically the supply side, have been intensively building.

And yet the secondary major cost from inflating a bubble in order to keep debt levels low has been to diminish the purchasing power of citizenry, so aside from domestic price inflation, this can now be seen in the falling peso. Government debt has been and continues to be subsidized by the private sector in possession of the currency, the peso.

A third major cost has been the illicit and immoral transfer of resources not only to the government but also to politically connected firms who has and continues to benefit from the BSP sponsored redistribution. Such has concentrated benefits to a few but has distributed the risks and the costs to the rest of non-beneficiaries, including this analyst.

A fourth major cost is that bubbles have effectively heightened “financial stability risks”. The BSP has created and unleashed an inflation ‘Godzilla’ which they proclaim they wanted to slay but seem to have second doubts.

Yet credit inflation has increasingly been concentrated to a few Philippine version of “too big to fail” companies. Meanwhile stock Market PE ratios of blue chip companies are at a stunning 30-60 and equally shocking has been the price to book value which have significantly been valued above 3. Such financial instability risks include the suppressed yields of Philippine treasuries which continue to reflect on the artificially priced convergence trade. The latter has been instrumental in the misallocation and redistribution of resources transmitted via the interest rate channel.

A fifth major cost is that resources channeled to the bubble sectors are resources that should have been used by the market for real productive growth. Much of these resources are now awaiting reappraisal from the marketplace via a shift in consumer’s preferences which will render much of these misallocated capital as consumed capital.

A sixth major cost is that once the bubble implodes, government revenues will dramatically fall while government spending will soar as the government applies the so-called “automatic stabilizers” (euphemism for bailouts). This would also extrapolate to a phenomenal surge in debt levels. All these will unmask today’s Potemkin’s village seen in the fiscal and debt space.

And the most likely response would be to increase taxes which should further penalize real economic growth. I expect sometime in the future the Philippine government will raise E-VAT to 15%[22].

A seventh major cost is that not only will a bust imply possible curtailment of civil liberties but the onslaught against economic freedom in particular the informal economy will likely intensify. This will come with more mandates, regulations and other restrictions. A government deprived or starved out of taxes for her insatiable spending appetite will desperate seek a larger tax base whose resources they intend to seize by taxation.

There may more but grant me the leeway such that I do not possess all the knowledge required as of this writing.

Nonetheless the cost benefit tradeoff reveals why the BSP will unlikely use the interest rate policy tool unless they have been forced by the marketplace.

Bastiat’s Unheeded Warning for the BSP

Going back to the BSP’s citation of the great Bastiat

I’m sad that the good BSP chief may not have read the book he excerpted. It would have given him a gem of an insight that may have prevented such risks from spreading and burgeoning. But yet again in doing so he may not be the anointed.

Here is Mr. Bastiat’s response to state guaranteed loans, or we might say the BSP’s aggregate demand policies.

This solution, alas, has as its foundation merely an optical illusion, in so far as an illusion can serve as a foundation for anything.These people begin by confusing hard money with products; then they confuse paper money with hard money; and it is from these two confusions that they profess to derive a fact.In this question it is absolutely necessary to forget money, coins, bank notes, and the other media by which products pass from hand to hand, in order to see only the products themselves, which constitute the real substance of a loan.For when a farmer borrows fifty francs to buy a plow, it is not actually the fifty francs that is lent to him; it is the plow.And when a merchant borrows twenty thousand francs to buy a house, it is not the twenty thousand francs he owes; it is the house.Money makes its appearance only to facilitate the arrangement among several parties.Peter may not be disposed to lend his plow, but James may be willing to lend his money. What does William do then? He borrows the money from James, and with this money he buys the plow from Peter.But actually nobody borrows money for the sake of the money itself. We borrow money to get products.Now, in no country is it possible to transfer from one hand to another more products than there are.Whatever the sum of hard money and bills that circulates, the borrowers taken together cannot get more plows, houses, tools, provisions, or raw materials than the total number of lenders can furnish.For let us keep well in mind that every borrower presupposes a lender, that every borrowing implies a loan.

Has Mr. Bastiat’s principles come to haunt the BSP?

Why a Rotation to Emerging Market Stocks is Unlikely

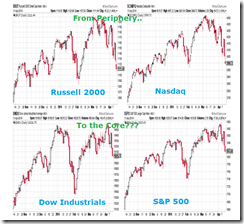

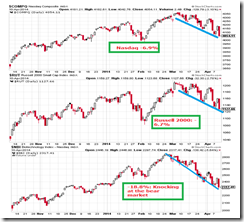

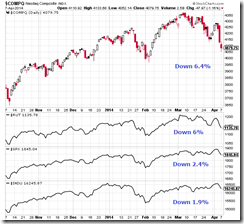

Developed economy stocks led by the US have been showing signs of pronounced weakness.

Unlike in January where the correction has been led by the blue chips (S&P—lower right and Dow Jones—lower left), we seem to be seeing a change in complexion.

First, volatility in both directions has become more pronounced. The downside bias appears to be picking up momentum. If the degree of fluctuations continues then this will reinforce my perception that this has been a topping process.

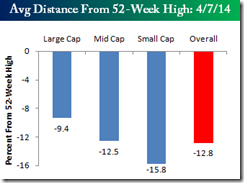

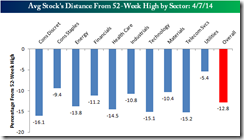

Two, as pointed out earlier[23], market breadth has significantly been deteriorating where the average stocks have been falling faster than the cushioned fall in the blue chips.

Third, one key barometer, the Nasdaq biotechnology index has been the first index to fall into a bear market.

Fourth, there are increasing signs of the periphery to the core in progress.

The periphery to core dynamic of the bubble bust cycle appears to be gaining strength. This can be seen through the growing signs of divergence[24]

This has been a long term process.

First to be affected has been commodities, then emerging markets. This has now spread to the developed economies. The initial impact in developed economies has been in the fringes: overpriced technology stocks. Now even the blue chips are affected.

Falling yields of the 10 year notes reinforces the sign of pressures on risk asset deflation.

Some experts have said that there has been an ongoing rotation from high flying technology stocks to emerging markets due to valuations.

I doubt that this logic has merit. First of all emerging markets like the Philippines has hardly been cheap at all. Emerging markets may seem cheaper than high flying technology but such comparison would be fallacious as this has been based on the contrast principle.

This leads us to the second factor: What drove popular stocks to their high flight status? If they are driven debt and if the current meltdown means liquidations from earlier leverage build up, then this would have an impact to the real economy. Sustained market pressures will hit overleveraged Wall Street firms first before the real economy—where the latter has hardly benefited from the FED’s subsidies.

Emerging markets have been slammed last year, but despite the sharp rallies in risk assets they haven’t been clean from debt. In fact the recent rallies have only whetted the appetite for debt where much of these may have been used to push up prices of risk assets.

Third just look at where the biggest rally in emerging markets comes from. In terms of emerging market debt, Argentina and Venezuela has been the biggest gainers from the recent rally according to JP Morgan see chart from February 3 to April 8th here.

Ukraine has been said to be part of the “tantalizing trio”. Ukraine’s stocks have also been astoundingly up by 40% year to date. And as I noted in the past Ukraine’s has the tendency to go stock market bubble blowing, she had two bubble bust in 2008 and in 2012 or in a span of 4 years. Ironically, Ukraine seems headed for a civil war.

And this is a striking comment as quoted by the New York Times[25] on the character of people piling into emerging markets.

“Many of the funds that are buying these companies don’t even know what they are buying,” said Elizabeth R. Morrissey of Kleiman International Consultants, an emerging-market investment monitoring and analysis firm. “All of a sudden, we have Joe Middle Class loading up on emerging-market bond E.T.F.s. That is a little frightening.”

My guess is that these are the same category of desperately seeking yield funds stampeding into Philippines equity assets with 30-60 PE ratios.

Phisix: Market Internals Point to a Steep Correction

As for the market breadth, I think retail punters have become exceedingly or wildly bullish on outrageously mispriced and overvalued Philippines equity markets.

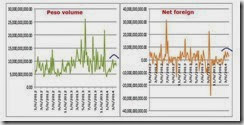

Retail players have been trading a broader segment of the market as shown in the Issues traded (averaged on a weekly basis) left pane. So the small number of moneyed retail punters has been bidding up on illiquid second-third tier issues, hoping to squeeze marginal yields.

Yet the last two times such level has attained, the Phisix had a 6% correction in March of 2013 and a 20+% in June 2013.

Such aggressiveness can also be seen in the average daily trade where retail punters have been churning more frequently. I don’t expect much new accounts. Average daily trade has surpassed the May highs and is at the August levels.

The last time such levels were reached we saw significant corrections.

I spoke about the likely class of foreign funds buying into outlandishly priced Philippine stocks, yet recent actions suggest that foreign buying though still positive has been in a slowdown.

Since foreign money accounts for a little more than half of the peso volume daily trade, the slackening of foreign activities has been mirrored by the Daily Peso volume.

The above only suggest that another interim significant correction may likely be next phase.

Nonetheless if the declines in the stock markets of developed economies worsen, then the supposed “animal spirits” that has backed much of the statistical growth figures will be exposed as a charade.

And as I recently wrote[26],

Such sustained risk off scenario will ricochet back to emerging markets where both the stock markets and the economies of developed-emerging market in tandem will substantially sputter. Then the Global financial-economic Black Swan manifested by the Wile E. Coyote moment appears.

If this becomes true, then what seems as a likely correction to occur may morph into a full bear market.

[1] Amando M Tetangco, Jr: Philippines – navigating through the global financial turmoil Australian-New Zealand Chamber of Commerce Philippines Annual General Membership Meeting, Makati-City, 14 April 2009 Bank of International Settlements

[2] Frédéric Bastiat What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen Library of Economics and Liberty

[3] Thomas DiLorenzo Biography of Frederic Bastiat (1801-1850) Frederic Bastiat (1801-1850): Between the French and Marginalist Revolutions Mises.org, Wikipedia.org Frédéric Bastiat

[4] Inquirer.net BSP hints at further monetary tightening, April 10, 2014

[5] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas End-March 2014 GIR Stands at US$79.8 Billion April 7, 2014

[6] See Phisix: BSP’s Response to Peso Meltdown: Raise Banking Reserve Requirements March 31, 2014

[7] See Behind the Furious Rally of the Philippine Peso April 10,2014

[8] Trade Union Congress of the Philippines Bangko Sentral urges government to end dependence on exports July 2, 2009

[9] Wikipedia.org Coincidence of wants

[10] See Typhoon Yolanda: From Natural to Man-Made Calamity; Spontaneous Order Thrives! November 18, 2013

[11] See Phisix: Will the Global Risk OFF Environment Intensify? February 3, 2014

[12] Ludwig on Mises Inflation Economic Policy Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow(1979), Lecture 4 (1958)] Mises.org p 62

[13] See Belarus Hyperinflation: Money Abhors a Vacuum June 23, 2012

[14] See Myanmar’s Property Bubble June 28, 2012

[15] See Japan’s Ticking Black Swan February 24, 2014

[16] Murray N. Rothbard E. The Government as Promoter of Credit Expansion Chapter 12—The Economics of Violent Intervention in the Market (continued) Man, Economy & State

[17] Henry Hazlitt THE INFLATION CRISIS, AND HOW TO RESOLVE IT p.58

[18] See Phisix Melts Up as Money Supply Growth Sizzles for the Eight Month April 7, 2014

[19] National Statistics Office Merchandise Export Performance : February 2014 April 10, 2014

[20] Wall Street Journal Real Time Economics Asia’s anti-corruption battle produces unofficial austerity April 9, 2014

[21] See Phisix: The BSP’s Self Imposed Hobson’s Choice March 9, 2014

[22] See E-Vat 15%: Possible Consequence from Current Quasi Boom Policies December 10, 2012

[23] See Signs of deteriorating US Stock Market Internals? April 8, 2014

[24] See Phisix Meltdown: A Reality Check on the Bullish Dogma June 10, 2013

[25] New York Times I.M.F. Warns of Risk From Emerging-Market Corporate Debt April 9, 2014