Fourth Touchdown into the Bear Market Zone

The Philippine equity benchmark, the Phisix touched the bear market zone for the FOURTH time since June 2013 this week. This comes amidst two successive weeks of heavy foreign selling where net foreign sales accounted for about 11.18% (Php 6.475 billion) of the two week volume of Php 57.9 billion.

However, in contrast to previous week, the Phisix resonated on the steep volatility of the US stock markets.

Monday’s over 2% slump by US stock markets rippled through Asian stock markets the following day. Japan’s Nikkei 225 suffered a quasi-collapse of 4.18% (-11.23% year-to-date), Hong Kong’s Hang Seng tumbled 2.98% (-7.16% ytd) while the Phisix tanked by 2.15%[1] (+2.06% ytd).

By the end of the week as US markets pole-vaulted to recover all of Monday’s losses to even close the week higher, e.g. S&P 500 +.81% (-2.78% ytd), where risk OFF abruptly morphed into risk ON.

Asian markets rallied sharply to shave off Monday’s losses. For instance the Nikkei posted a weekly 3.03% loss, the Hang Seng -1.81% and the Phisix -.5%. Indonesia and Thailand’s equity benchmarks the JKSE and the SETI even registered sharp gains 1.08% and 1.74% respectively.

Amazingly, even Singapore’s stock market broke below the September 2013 lows early this week, but like the Phisix, the STI rallied furiously by the week’s close.

The purpose of my reference to Singapore has been to demonstrate that financial stress hasn’t been limited to emerging markets but has begun to impact even developed economies.

This seems part of the periphery-to core transmission mechanism in motion.

And this also validates my repeated observations on the predominating character of stock market activities[2].

We should expect sharp volatility in the global financial markets (stocks, bonds, commodities and currencies) in the coming sessions. The volatility may likely be in both directions but with a downside bias.

Such volatility has hardly been manifestations of a bullish backdrop. Instead they seem like a varied strain of the 1994-1997 episode, which are reflections of a “toppish” or increasingly high risks financial markets.

Yet today’s degree of volatility has been muted relative to pre-Asian crisis landscape where then the Phisix endured a series of vertiginous rollercoaster swings marked by four sharp sell offs (3 of which had been bear market strikes) that had been accompanied by very ferocious denial rallies for two years (1994-1995).

The rollercoaster eventually transitioned into a bull trap. In 1996 to early 1997 the Phisix went on to recover the highs of 1994 (56% gain). But like all bull traps, the Phisix eventually succumbed to a full bear market cycle where the local benchmark hemorrhaged nearly 70% from the 1997 highs[3].

The fourth attempt by the Phisix last week to reach the bear market territory is a reminder of how treacherous today’s markets operate on.

Phisix and US Treasuries: the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea

Yet for many of those afflicted by the Aldous Huxley “facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored” syndrome they cling on to spurious logic in support of the bullish backdrop whose foundations are presently being eroded by signs of sustained rise in interest rates.

For instance many fail to see of the relationship between yields of 10 US treasury notes with the actions of the Phisix. The overlapped charts of the Phisix (PSEC) and 10 year UST yields (TNX) have shown of emerging correlations since May 2013.

Notice that each of the Phisix ‘lower’ peaks (blue ellipses) comes in the face of either low or bottom in UST yields. And that for each time the UST yield reach an interim apex (red ellipses) the Phisix bottoms. Put differently when UST yields begin to rise, this puts selling pressure on the Phisix and vice versa.

Yet if the current correlations persist then this implies that for the Phisix to have a sustainable upside move, US bonds should continue to rally or that yields should be in a falling streak. This should be conditional to US stocks trading either sideways or to the upside and NOT on the downside.

The fantastic two day rally in the US stock markets (of more than 2%) last Thursday and Friday provides us some clues.

Excess volatility has pervaded into the US bond markets too. Monday’s US stock market selloff incited a fierce rally in US bonds (where yields collapsed). US bonds fell (yields rose) from Tuesday until Thursday, in response to Monday’s sharp rally (falling yields). The yield spike in Wednesday was followed thru in Thursday. By Friday, much of Thursday’s yield gains had been reduced. 10 year USTs ended the week very little change despite the wild pendulum swings over the week.

What activities influenced both the actions of the stock and bond markets? The gains of US stocks and rising UST yields came amidst anticipation of a strong jobs report for Friday.

At the same time, ECB’s Mario Draghi floated a “teaser” for the Wall Streets spanning the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The ECB reportedly would act by March “to counter low inflation”, this partly by suspending sterilization or “ending the absorption of crisis-era bond purchases” in order to flood Europe’s system with more liquidity[4].

Also the US government reported that trade deficit widened as exports fell[5].

[As a side note, I have been saying[6] the reason why the Fed has resorted reluctantly to the “taper” has been because of the looming shortages of debt papers issued by the US government due to improving twin deficits in both budget and trade. Wider trade deficit means more leeway for the Fed to cease with “tapering”]

So while the anticipation of good news in the job markets resulted to higher yields, the gains appear to have been capped by the signalling of monetary easing from the proposed unsterilized injections by the ECB and from a wider US trade deficit.

Thus the scent of monetary heroin sent stocks into a Risk ON “high” mood.

Friday confirmed Wall Street’s addiction to monetary heroin. Aside from increases in earnings of several companies, the disappointing job report heightened the speculations for monetary easing, as this news report implies, the Fed has been “scrutinizing employment data to determine the timing and pace of cuts to stimulus”[7] So the “bad news is good news” has sent stocks into another overdrive session as bond yields fell.

But there is a big hole with the concept of a sustained decline of yields of USTs considering the record borrowing in the bond market which has now spilled over to banking system.

For instance fund withdrawal from emerging markets, has reportedly further fuelled a “doubling down” of Wall Street’s buying in junk bonds[8]

As the Bond King PIMCO’s William Gross rightly explains[9] (bold original)

Asset prices are dependent on credit expansion or in some cases credit contraction, and as credit goes, so go the markets, one might legitimately say, and I do most emphatically say that!

A sustained inflationary boom in the US would mean higher bond yields due to greater demand for credit and/or due to rising pressures on price inflation mostly on the input prices in support of the bubble sectors.

In other words, for as long as the US stock market bubble inflates, there will pressure on yields of USTs to rise. On the other hand, if US stock markets convulses, this will likely be accompanied by a slowdown in credit thus rallying bonds.

The proof of the latter has been a record outflow from stocks to bonds in the US (US $24 billion) and the world (US $28 billion) in the week through February 5[10].

This bring to fore a devil and the deep blue sea paradox for Emerging Markets including the Phisix. The era of rising stocks amidst low interest rates have increasingly become outmoded. Rising stocks in the US or developed economies will most likely be backed by higher UST yields. This means pressure on emerging markets financial markets.

On the other hand, falling stocks in US and developed economies accompanied by rallying bonds would signal ‘asset deflation’ which will likewise put a lid on any rally for emerging markets.

So the escalating volatility in US treasuries have hardly provides for a bullish backdrop on Emerging Markets and the Phisix.

Direction of US Treasuries as Prognosticator of Emerging Market Money Policies

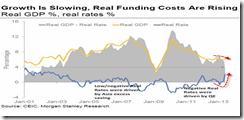

It’s not just in the correlations in the financial context, rising yields of USTs will soon be revealed in monetary policies of the world. The Emerging Market turmoil represents a symptom of such unfolding progression.

Relative yield spreads in EM will have to adjust in accordance to the directional path of the yields of USTs.

Remember the US dollar remains as the world’s primary reserve currency as shown in the above chart[11]. 86% of the world’s transaction has been facilitated by the US dollar. 64% of the international currency reserves are in US dollar. 46% of debt securities have been priced and issued in US dollar. 65% of the banknotes held overseas are denominated in US dollars and so with cross boarder deposits and banking loans, 59% and 52% respectively.

In short, global trade and finance have been deeply anchored on the US dollar which have been partly reflective of the conditions provided by the monetary policies of the US Federal Reserve. Thus actions of US dollar assets will have material influence in shaping EM policies.

So if yields of UST climb, the rest of the world will follow suit. But this will follow a time consuming process and won’t happen overnight.

Since EM economies took excessive debt in order to generate statistical growth when USTs were low, the coming adjustments would naturally expose on these unsustainable growth models

And symptoms of such adjustments, which so far have been disorderly and violent, have been substantially weaker currencies, higher inflation, foreign outflows and subsequently rising rates (e.g. Turkey, India, Indonesia).

Such adjustments will be seen in the Philippine arena. This has not only been via a falling peso, the pressures are now being felt by the tightly controlled (by government and their allied private sector banks) and less liquid domestic bond markets.

As a side note, for the first time in 2014 or in 5 successive weeks, the Philippine peso rallied to 44.985 vis-à-vis the US dollar this week. This is likely a dead cat’s bounce.

From the short end (1 month) to the mid curve 5 year to the benchmark rate (10 year), the latter usually has been used as basis for the lending rates, to even the long curve the 20 year (not in the above chart), yields across the curve have all reached June 2013 levels. 5 and 20 year yields have even surpassed the June highs. Remember, the crash in domestic bonds which saw a spike of yields in June has been in consonance with the first bear market encroachment by the Phisix over the same period.

Some questions for the bulls: how will rising rates influence the financial positions of over indebted or overleveraged companies? How will rising rates impact credit quality? What will be the ramifications of rising rates to the real and statistical growth aspects of the demand side and the supply side? How will rising rates impact demand and supply of credit? How will higher interest rates amidst high debt levels be bullish for the stock markets? How will high interest rates in the face of relatively higher debt levels today be bullish for foreigners?

An even more important question is why has the Phisix been sensitive to the movements in the 10 year UST notes, if indeed “fundamentals” have been indeed sound as alleged?

Pardon my appeal to authority, but one of the former major defenders of the status quo, Emerging Market guru Franklin Templeton’s Mark Mobius, who earlier predicted that foreign flows will revive in 2014 due to “fast economic growth, low debt relative to gross domestic product and high foreign-exchange reserves” apparently made a volte face in declaring just the other day, that EM outflows will “deepen” or intensify[12].

Whatever happened to the standard mantra of “fast economic growth, low debt relative to gross domestic product and high foreign-exchange reserves”?

We don’t even look far ahead to see how confused policymakers have been in wavering from one stance to another.

Take for instance the Wall Street Journal notes of a dithering BSP governor Amando Tetangco, who allegedly said a few days back that policy interest rates is “not necessarily the most appropriate response at this time”. But in the face of rising statistical inflation the same article quotes the BSP governor, “We still have room to keep rates steady, but given how these factors play out, that room may be narrowing,” Mr. Tetangco said in a text message to reporters after the data release. “We will see if any adjustments to the stance of policy are warranted based on the balance of these risks to the inflation outlook over our policy horizon”[13]

First BSP officials have been hesitant to use the interest rate channel but updated inflation data[14] seem to have painted the BSP into the corner. Has the BSP been revealing increasing signs of desperation?

For the BSP, who have been blindsided by the adverse effects of soaring M3 (add to this soaring deposit levels), has the inflation chickens come home to roost?

It’s important to add that the BSP data for December[15] shows a still stunning 32.7% jump in M3 growth year on year where claims on the private sector and on other financial corporations constitute 67.83% of December M3. (no credit bubble?)

Not only has soaring M3 been a major symptom of the unsustainable credit boom underpinning the artificial statistical growth, the falling peso has been another transmission channel for higher consumer prices since the Philippines buys more than she produces as evident by her sustained balance of trade deficits.

If rising bond yields have been signs of upcoming consumer price inflation which means a reduction of purchasing power by consumers or a reduction in disposable income, how will this be bullish for the economy and the stock market?

Essentially the BSP’s concerns could be a validation of the results of the recent surveys depicting a serious deterioration of the outlook of the general populace over the quality of life as noted last week[16].

And whatever happened to the much hyped foreign currency reserves? The BSP data reveals that forex reserves[17] stumbled by 5.17% last month and 7.42% from a year ago due purportedly to “foreign exchange operations of the BSP and payments by the National Government (NG) for its maturing foreign exchange obligations”.

Has the BSP been massively selling US dollars to shore up the Peso in January? Yet despite the about $4 billion in interventions the peso lost 2.07% over the month.

Will forex currency reserves fail to work as “elixir” as so-claimed by worshippers of the bubble? Will this prove my thesis that forex reserves are symptoms of bubbles rather than signs of strength[18]?

And why the state of confusion by BSP officials?

Because of the resistance to realize that domestic yield spreads would need to be adjusted to reflect on the changes in interest rates of the US. Since the BSP mimicked on the FED’s zero bound rate policies, naturally any aftereffects of the latter will most likely be reflected on the former’s operating environment as presently expressed through the unfolding developments in the financial markets and in the real economy. See the M3 example and the January losses in forex reserves.

The major flaw of the mainstream economic experts, who really are statisticians masquerading as economists, has been to project the past as operating in a linear motion into the future. Yet there have been little incentives for them to understand of the causal realist link or the entwined cause and effect relationships between markets and policies. Besides, incumbent bureaucrats are naturally expected to be salespeople of any administration everywhere, so everything will look rosy until it isn’t.

Remember late last year I noted how the interest rate spread between the US and Philippine 10 bonds have narrowed to a record 78 basis points which I called the convergence trade[19]?

Presently this spread has widened to 168 bps (as of Friday) which has unfortunately been accompanied by market distress. Yet I expect a reversion to the mean in yields of UST and Philippine treasuries to occur sometime and I doubt if this will be in an orderly manner.

And if interest rate levels, for the mainstream, serve as a reflection of creditworthiness of a nation, then what justifies such record interest rate convergence? Statistical economic growth predicated on the actions of mostly the less than 20% of the households whom have access to the formal banking and capital markets? And statistical growth founded on a credit boom which distributes the risks and the benefits to a concentrated few?

And how can a nation with a nominal per capita GDP of US $2,611 (IMF 2012) with a relative underdeveloped banking and financial system, implying the paucity of intermediation channels of savings into investments and equally indicative of high costs of, and limited access, to capital, as well as, high transaction costs and inefficient facilities for capital accumulation, establish a position as being more creditworthy, than say, compared to New Zealand with a nominal per capita GDP of US $38,225? (IMF 2012)

Yield of New Zealand 10 year treasuries have been priced at 4.59% as of Friday which still remains higher than the Philippines.

As reminder yield spreads are based on domestic currencies which even accentuate the grotesqueness of domestic bond market mispricing. Lower rates for the peso postulates to less currency risk for the peso relative to the New Zealand dollar, for instance. All these premised on the less than 20% of households!

Yet it would seem that in a milieu where investors have been conditioned like Pavlov’s dogs through central bank policies to chase yields, running a façade of anti-corruption theatrics combined with a puffery in statistical growth data has been enough to pull the proverbial wool over the eyes of the indiscriminate money allocators.

Well economic reality seems as knocking on the door.

Waking up to the fact that the Philippine Economy has been in a Bubble

Speaking of credit driven statistical economic boom, the BSP finally released their yearend data for 2013[20]. This gives me the opportunity to combine both BSP and NSCB data and see whether the highly acclaimed Philippine economy have been founded on sound principle or from a bubble.

As I noted last week, I find it unusual for timing of the Philippine government’s early release of the NSCB’s statistical growth data when the BSP publishes loans data a month ahead of the latter.

BSP data reveals that based on nominal peso, loans to the construction sector (right) as well as the real estate sector (left window, green line) has gone parabolic since 2010.

Meanwhile banking loans issued to the trade (wholesale and retail, blue line left window) and financial (red line; left window) industries has likewise accelerated over the same period.

A better perspective can be seen in year on year % change window, where the country’s credit boom can be seen accelerating from 2010, particularly for the real estate, financial, trade and construction sectors, as well as the banking system’s overall loans. For the trade and financials sectors, the boom peaked in 2012, where the loan growth astoundingly ballooned by 43% and 31.75% respectively. Yet despite the slowdown, trade and financial loans remain at 13.82% and 11% in 2013 respectively. The average growth for the past 6 years has been at 20.21% for trade and 13.3% for financials.

Loans to the real estate sector marginally slowed in 2013 but remains at 23.24% after a high of 25.64% in 2012. The average growth over the past 6 years has been at 20.34%.

Meanwhile the construction sector continues to sizzle where loan growth for 2013 skyrocketed by 51.36%. The average loan growth in the past 6 years has been at 19%

Such fabulous growth rates, which have been vastly above general statistical growth, divulge of the extent of leverage being amassed by the underdeveloped banking and financial system to (as I suspect) a few but big players of the abovementioned industries.

The mainstream defense says “low debt levels”. True, if we apply this to the general formal economy. False if this is seen in the prism of credit growth rates of specific industries. Yet the more the concentrated the credit exposure has been, the bigger the risks of a Black Swan.

As a side note, not every firm from the industries registering significant credit growth rates share the same degree of loan exposures or credit risks. Either a majority of the firms in the industry has significant credit exposure or that the issuance of large credit volumes has been tilted towards a few big firms. I suspect the latter than the former.

Now for the juicier aspect.

In the above table, NSCB’s growth data[21] has been shown side by side with BSP banking loan data in terms of % share and growth rates.

On the left section of the table is the % share of the industries, which I suspect, as having been plagued by a massive credit bubble.

Total contribution of these bubble sectors—specifically in trade (wholesale and retail or the shopping mall bubble), financial (bond and stock market bubble), real estate and construction, and hotel (casino bubble) industries to the Philippine gdp in 2013—accounts for 44.84% of the statistical economy. This compares with the 49.61% share of banking loans issued to these sectors.

If we add to the non-bubble manufacturing, share of gdp growth of the above mentioned sectors have been at 65.2% for gdp and 68% for banking loans.

The point of the above exercise is to show the size and scale of banking exposure on a significant critical segment of the statistical economy. In short, a bubble bust will tend to have a major direct impact on the statistical economy, aside from the potential contagion.

As reminder, bubbles are hardly about generalized credit exposure but on the malinvestments or misdirected investments towards the heavy capital goods industries such as construction, and titles to these capital goods, such as the stock market and real estate[22]. This is also the reason why I included the manufacturing sector which so far has shown little signs of credit boom.

The right side of the table has a very illuminating picture of how banking loans extrapolated to statistical growth.

I should be jumping in joy to say that growth in the loans to the financial sector at 11% produced 15.7% of statistical economic growth. This means that 70 cents credit produced 1 peso growth for the financial sector in 2013. The 30 cents should translate to productivity growth. But I would suspect that the numbers may not reveal its true dynamics considering that the financial intermediaries consist mostly of banks and non bank financials and to the lesser extent insurance.

The loan growth by the manufacturing sector at 7.6% relative to the supposed output at 8.6% explains why I don’t consider the domestic manufacturing a bubble. The manufacturing sector has been producing more than they have been borrowing.

Yet what appear as quite disturbing have been in the growth figures of the construction, real estate and hotel industries. For every 1.9 pesos of loans acquired by the real estate sector generated only 1 peso of additional growth. More staggering has been the proportionality of each peso growth for the construction and the hotel industry that has been financed by borrowings of 3.25 pesos and 2.7 pesos respectively.

Why such large discrepancies? Has costs of these projects ballooned faster than expected for developers to seek more financing? Or are the large gaps symptoms of deep inefficiencies of these industries? Or has politics played a role in the additional costs incurred by these sectors? Also have the money borrowed by these sectors been diverted into other ventures?

The figures indicate that growth in these industries have hardly been enough to finance current projects thus the recourse to more loans. This also means some companies may have resorted to ‘debt-in debt-out’ as a way to go around their routine activities. This also points to the increasing sensitivity by these sectors to the fluctuations in interest rates or particularly the deepening dependence on the perpetuation of zero bound rates.

Such developments reveal why the BSP officials have been hesitant to tighten monetary policies or why inflation data has caught them off guard.

In a latest interview with the CNBC[23], the good BSP governor declares a ‘this time is different’ dynamic which allegedly will bring about renewed interest in the Philippine economy. He says that investors will “wake up to the fact that the Philippines is different” and that “investors will focus on the fundamentals again and come back to countries like the Philippines”

I believe he is correct in a sharply contrasting sense. When investors focus on the real fundamentals, and not just ‘shouting’ statistics, they will “wake up to the fact” that the Philippine economy, like most of the economies in the world today, has been in operating in an unsustainable bubble backed by a severely maladjusted economy (weighted heavily to those with access to the banking sector), vastly mispriced assets and the obstinate refusal by policymakers to calibrate their policies to reflect on the current developments in the hope to perpetuate a quasi-permanent boom.

Conclusion and recommendations

-Expect wild gyrations in the global and local financial markets (be it in stocks, bonds and or currencies). The outsized volatility will come in both direction but eventually the downside bias will reassert dominance.

-The extent of volatility is a manifestation of a toppish process and underscores amplified risks which hardly is a bullish environment

-Technically and factually, the Phisix is in a bear market. Therefore until proven wrong, the path of least resistance should be on the downside.

-Emerging markets and the Phisix are all tied to the actions of US monetary policies or bond markets. The nasty side effects of both US and domestic policies are being felt in the local arena.

-Domestic officials will continue to resist adjustments in policies in the hope that boom days will return. The substantial fall in January's forex reserves is an example of such resistance to change. However the more officials resist, the more volatility will occur.

-Price inflation seems now a real concern. Deteriorating sentiment on the quality of life, sinking peso, rising bond yields across the curve and the BSP has been caught in a bind appear to be reinforcing this.

-Price inflation means redistribution of spending patterns. Considering that the Philippine consumer are highly sensitive to food, transportation and energy inflation a rise in inflation translates to diminished disposable income. This means consumer spending will be hobbled. This also means a slowdown on real economic growth.

-Use any rebound to decrease exposure on popular themed stocks, particularly those exposed to shopping malls, real estate, so-called consumer spending stocks and financials (banks and non-banks). Today’s high risk environment will hardly be an issue of return ON investment this will be an issue of return OF investment

-On the urge for stock market exposure. Again avoid popular issues. Choose issues with little or no debt. Choose issues eschewed by the public or by mainstream analysts. Or choose non-popular stocks that have been sold down heavily (more than 50% off the highs) or has flat lined through the boom. Should a black swan occur these stocks are likely to have limited downside. Avoid aggressive positioning.

-There is one reason to be in stocks. Should a global black swan occur in 2014 or 2015, I expect some if not many governments to use Cyprus bail-in or deposit haircut policy paradigm as a way out of the mess. It is not clear though which government/s will resort to them. The stock market can serve as safehaven from such bank deposit confiscation. But timing will be necessary here.

[1] See Asian Risk OFF Day: Japan's Nikkei Dives 4.2%, Singapore’s STI Breaks Support, Yields of Indonesian Bonds Soar, February 4, 2014

[2] See Phisix: A Bull Trap and the Switch to a Global Risk OFF Mode? January 25, 2014

[3] See Phisix: Don’t Ignore the Bear Market Warnings June 30, 2013

[4] Bloomberg.com Draghi Signals ECB Ready to Wait Until March for Action February 7, 2014

[5] Reuters.com U.S. trade deficit widens in December as exports fall February 6, 2014

[6] See Phisix: Will a Black Swan Event Occur in 2014? January 13, 2014

[7] Bloomberg.com U.S. Stocks Cap Best 2-Day Rally Since October on Economy February 8, 2014

[8] Bloomberg.com Contagion Rejected as Biggest Bond Buyers Double Down on Junk February 6, 2014

[9] William Gross Most Medieval

[10] Bloomberg.com Investors Shift Record Amounts From U.S. Stocks to Bonds February 7, 2014

[11] Zero Hedge Triffin's Dilemma: The 2014 Edition February 5, 2014

[12] See EM Guru Mark Mobius changes outlook, says EM outflows will continue February 8, 2014

[13] Wall Street Journal Real Times Economic Blog As Prices Rise, Philippine Banker Fires Warning Shot on Rates February 5, 2014

[14] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas January Inflation Slightly Higher at 4.2 Percent January 30, 2014

[15] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, Domestic Liquidity Growth Slows Down in December January 30, 2014

[16] See Phisix: Will the Global Risk OFF Environment Intensify? February 3, 2014

[17] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas End-January 2014 GIR Stands at US$78.9 Billion February 7, 2014

[18] See Emerging Market Turmoil: The Fallacy of Foreign Currency Reserves as Talisman February 3, 2014

[19] See Phisix: The Convergence Trade in the Eyes of a Prospective Foreign Investor November 11, 2013

[20] Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Bank Lending Continues to Expand in December January 30, 2014

[21] National Statistical Coordination Board. Philippine Economy Grew by 7.2 percent in 2013; 6.5 percent in Q4 2013 January 30, 2014

[22] Murray N. Rothbard, 15. Business Fluctuations Chapter 11—Money and Its Purchasing Power (continued) Man, Economy and State

[23] CNBC.com Investors will wake up to Philippines 'pretty soon': Central bank February 6, 2014