Regional Financial Weakness Spreading

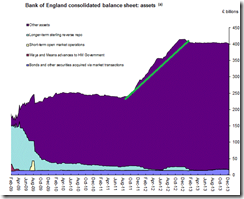

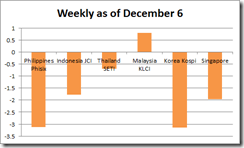

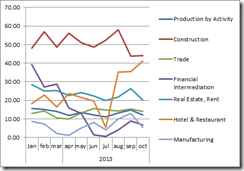

Except for Malaysia, ASEAN equities have mostly been losing ground.

This week’s biggest losers were spearheaded by the Philippine Phisix (-3.12%) and surprisingly Korea’s Kospi (-3.15%) along with Singapore’s Straits Times (-1.96%) in apparent sympathy

And what appear as more disconcerting have been signs of renewed weakness in most ASEAN currencies with the exception of Malaysia’s ringgit.

As a reminder the last time the USD-rupiah set September highs ASEAN stocks endured the second phase of the meltdown after June. So instead of a crash, the current infirmities seem to have evolved towards a more subtle or gradualist decline in the region’s equity markets…again with Malaysia as the outlier.

Malaysia’s Divergence: Leading or Trailing Indicator?

Perhaps part of Malaysia’s exceptional financial performance may have been due to the recent announced reforms as alleged by mainstream media. Given the fresh mandate from the recent elections, Prime Minister Najib Razak has targeted a reduction of the government’s 2014 budget deficit to 3.5% from earlier projections of 4% mainly due to a reduction in subsidy programs. The Malaysian government plans to trim spending on sugar and various fuel subsidies from 18% of government spending to about 15.6% in 2014[1]. This indeed should signify a welcome development.

But a decrease in subsidies should extrapolate to a one shot jump in CPI inflation. However Malaysia’s consumer price inflation has turned the corner since January 2013[2] and been inching up even prior to the elections and to the publicised reforms.

Credit rating agency Moody’s recently raised Malaysia’s credit outlook and foreigners were reported to have flowed back into Malaysia’s bond markets in October[3]

The share of holdings of Malaysian bonds has been at 42.8% in the 3rd quarter down from 46.8% in the 2nd quarter according to the same report. So which entity has been responsible for the bond liquidations? Have residents been shifting to stocks by selling bonds to non-residents or foreigners, ala in the US, thus rising stocks and appreciating ringgit as Malaysian bonds fall?

As pointed out above, foreigners own a significant share of Malaysian bonds. However in terms of equities, foreign exposure has been comparable with the Philippine Phisix (15-16%) which alternatively means significantly less relative to Indonesia (22%-23%) or Thailand (25%).

Have foreigners seen Malaysia as immune to inflation, currency, credit and contagion risks?

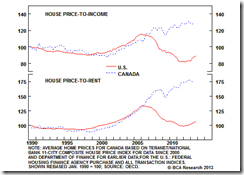

The irony has been that, at the close of November, another credit rating agency the S&P downgraded FOUR Malaysian banks “on concern that rising home prices and household debt are contributing to economic imbalances in the country”[4]

Since January of 2012 Malaysia’s loan to the private sector has ballooned by 21%[5], given that housing prices[6] have retreated in the 2nd quarter supposedly in part due to newly instituted curbs[7], has all these yield chasing been shifting to stocks?

The bottom line is that the actions in Malaysia’s stock market and currency market appear to have diverged from that of the domestic bond markets as well as financial markets in the region. Will such disparity last? Will Malaysia lead the region out of the languor? Or will Malaysia be the last shoe to drop?

Philippine Bubble Goes Mainstream; the Deposit Bubble

It’s is one thing where columnist/s of popular website/s or conventional media outlet/s make the case for a bubble and it is another thing when bubbles are reportedly casually as part of everyday news. The latter is what I would call as bubbles getting into the mainstream’s radar screen.

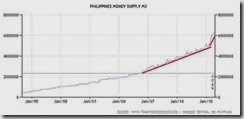

Recently in the economic section of the Wall Street Journal Blog, several mainstream economists raised concerns over the exploding money supply in the Philippines which raises the risks of a bubble.

Philippine M3, according to the report, rose 32.5% in October from a year earlier — the fourth straight month it has grown by more than 30%, and a possible warning sign of future asset bubbles[8]

The article points to the Special Deposit Accounts (SDA) as the culprit.

Since 2007, the rise in Philippine M3 has been accelerating faster compared to the previous years. This year M3 has gone nearly vertical[9].

The BSP recently reported that “Domestic claims grew by 11.6 percent in October from 10.9 percent (revised) in September due to the continued increase in claims on the private sector (by 16.2 percent), in line with the sustained growth in bank lending. Meanwhile, net claims on the central government rose slightly by 0.5 percent in October, largely as a result of the increase in credits to the National Government.”[10]

Combined claims on the private sector and claims on other financial corporations account for 78% of domestic claims, which implies that the gist of the jump from M3 comes from mostly credit expansion.

SDAs have been responsible for the recent spike in M3 but hardly have been main force behind sustained M3 growth over the last few years.

Introduced in 2006[11], SDAs have been designed as an instrument to mop up excess domestic liquidity.

Unfortunately, the BSP failed to anticipate the avalanche of deposits that accrued to SDAs, which has resulted to steep financial losses for the domestic central bank.

The BSP initially resorted to rate cuts below policy rates (see right window), but this has hardly dissuaded banks from parking funds in the SDAs (see left window)[12].

The BSP eventually banned “individual investments in SDAs” channelled through Investment Management Accounts (IMA) via the banking system; the deadline of which lapsed a week prior to December 2013. Although the BSP allows individual investments via unified investment trust funds (UITF) or other similar pooled instruments[13]

Nobody seem to be asking why deposits seem to be surging and where such has emanated?

The simple answer is that when the banking system underwrites a loan (issues money out of the thin air), which gets spent by the borrower, the fund flow from such transactions (with the suppliers or providers) or from other consequent transactions mostly ends back in the banking system as deposits.

[Note: these are transactions on the formal economy. As a reminder, only 21 out of 100 households have access to the formal banking sector. Although some of these transactions have spilled over to the informal sector]

As the great dean of the Austrian school of economics Murray N. Rothbard explained[14]

Now what happens when banks print new money (whether as bank notes or bank deposits) and lend it to business? The new money pours forth on the loan market and lowers the loan rate of interest. It looks as if the supply of saved funds for investment has increased, for the effect is the same: the supply of funds for investment apparently increases, and the interest rate is lowered. Businessmen, in short, are misled by the bank inflation into believing that the supply of saved funds is greater than it really is. Now, when saved funds increase, businessmen invest in "longer processes of production," i.e., the capital structure is lengthened, especially in the "higher orders" most remote from the consumer. Businessmen take their newly acquired funds and bid up the prices of capital and other producers' goods, and this stimulates a shift of investment from the "lower" (near the consumer) to the "higher" orders of production (furthest from the consumer)—from consumer goods to capital goods industries

In short, the Philippine banking system’s 5.730 peso deposit liabilities (as of September) have been a manifestation of expansionary banking credit.

3rd quarter’s peso deposit liabilities which accounts for 83.31% of the banking system’s deposit liabilities, also represents 9.45% growth from the second quarter and 22.6% jump from the 1st quarter.

The huge jump in deposits nearly squares with the growth of banking loans. In 2013, the average quarterly growth of deposits has been at 15.5% while average monthly growth rate for banking loans has been at 13.4%

The BSP recognized this dilemma way back in 2006 and so has been the reason why the Special Deposit Account came into existence: to “absorb excess liquidity”.

Unfortunately in the face of concerns over M3 growth the BSP chief Amando Tetangco sidesteps on the issue and replied with abstract responses such “trust” on the banking system who are making “very deliberate choices” in issuing loans or that “banks will continue to be discriminating”. Also the BSP chief has so much confidence regulatory responses “The BSP stands ready to deploy appropriate measures as needed to ensure that liquidity conditions to be in line with the BSP’s objective of maintaining price and financial stability”

Yet the BSP chief didn’t even bother to explain why the SDA program went against the “BSP’s objective”

In addition, following a surge in September loans to the banking sector mainly from the "higher" orders of production or capital goods industries which delivered the mainstream’s expectations[15] of “transformational”[16] statistical growth, rate of loan growth in October slumped, based on BSP’s latest data[17].

This looks like a similar pattern in July where the banking system’s loan growth went into a reprieve but eventually bulged at the end of the quarter. It looks as if banking systems loans have been programmed for an unstated reason. But should the rate of growth of banking loans continue slowdown this will be reflected on the statistical economic growth.

BSP’s Inflation Model Sees M3 as Operating in a Black Hole

Putting statistics aside, in the real world Liquidified Petroleum Gas (LPG) prices jumped by about 20% which media blamed on foreign dynamics (hardly an accurate account as global energy prices have been either moving down or sideways[19]) and to domestic power plant maintenance shutdown.

LPG is part of the array of energy and fuel costs that are about to rise.

What media fails to account for is that since the Philippine President declared a “state of calamity” last November[20] in the aftermath of Typhoon Yolanda, where LPG has been covered by “automatic price controls” under Republic Act No. 10623 or the law amending certain provisions of the Price Act (RA 7581) for 15 days[21], price controls always leads to shortages.

With soaring M3, which has been a symptom of excessive banking credit growth that has artificially been boosting demand for the first recipients of banking loans and for the initial beneficiaries of government spending in combination with mandates that induce supply imbalances, e.g. price controls, the Philippine government has put into place key ingredients for greater risks of stagflation regardless of what statistics say.

The BSP attributes[22] the current run-up in domestic CPI to “temporary supply-side factors at play”, although such figures have supposedly been “in line with the BSP’s assessment of a benign inflation environment over the policy horizon” which the means the BSP is in a self-congratulatory mode despite the uptick in CPI: “affirms the appropriateness of the current monetary policy stance”.

The BSP’s M3 data apparently has been vaporized in the BSP’s inflation model.

San Miguel Corporation’s Debt In-Debt Out Accelerates

Publicly listed San Miguel [PSE:SMC] seems as a wonderful example of whether domestic financial institutions have been making “very deliberate choices” in extending loans

Before I proceed first a reminder, as I previously noted[23]

The following doesn’t serve as recommendations. Instead the following has been intended to demonstrate the shifting nature of business models by major firms particularly from organic (retained earnings-low debt) growth to aggressive leveraging or the increasing use of leverage to amplify or squeeze ‘earnings’ or returns, the deepening absorption of increased risks in the assumption of the perpetuity of zero bound rates, and how accrued yield chasing by the industry induced by zero bound rates has pushed up property prices

I have noted how San Miguel’s finances looked vulnerable last September. With the sale of San Miguel’s entire Meralco holdings I expected improvements on SMC’s financial conditions.

SMC was supposed to raise something like Php 100 billion pesos from the Meralco sale. But it seems that this has barely been reflected on her 3rd quarter financial conditions

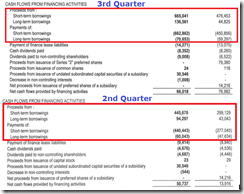

Based on the latest SMC investor briefing[24] compared with the 2nd quarter[25], while cash balance of SMC increased by Php 45.5 billion, interest bearing debt likewise swelled by Php 25.4 billion, albeit less than the gains in cash. The former probably accounts for part of the proceeds of the Meralco sale.

It’s nice to see improvements in SMC’s business conditions. This has been manifested in free cash flows particularly in cash flows from operating activities. For the third quarter, SMC’s cash position has ballooned by 102.6% to Php 36.189 billion from the same period last year at Php 17.867 billion and by 234.74% as against the 2nd quarter at Php 10.811 billion.

But despite the splendid improvements in operations, unfortunately SMC’s free cash flows have hardly been enough to cover her debt financing, whether interests or principal amortizations.

To the contrary, SMC’s 3rd quarter[26] short term and long term borrowings which totalled Php 801.602 billion represents a stunning 48.45% jump in borrowing relative to the 2nd quarter[27] at Php 539.975. Note that in both the 3rd and 2nd quarters, the amount that SMC borrowed ended up paying almost what she owed + morsels in terms of dividends and etc…

The 3rd quarter shuffling of debt has nearly reached the entire 2012[28] operations where SMC raised Php 812.628 billion in short and long term borrowings to pay for nearly a symmetrical debt.

The 3rd quarter update only means SMC will likely close the year with far larger debt than in 2012.

In the race to close debt gap, SMC’s businesses will need to see an explosion in productivity growth to keep in pace with soaring debt levels, a task that increasingly seems improbable with the rate of debt increases.

San Miguel’s recourse to ‘debt in and debt out’ increasingly exhibits the neo-Keynesian Hyman Minsky’s symptoms of “Ponzi financing”[29] where debt strapped firms borrow to pay interest or sell assets to pay interest (and even dividends). Unfortunately such actions “lowers the equity of a unit, even as it increases liabilities and the prior commitment of future incomes”. In short for debt holders, “Ponzi finances lowers the margin of safety that it offers the holders of its debts.”

Mr. Minsky’s germane and keen observation appears to have initially been realized as SMC’s equity prices seem as in a downdrift even as debt in- debt out operations continues, and importantly, has been immensely expanding.

[A side note, even if stock markets rally, this won’t be enough to offset the deepening use of debt in-debt out which only magnifies the risks of a credit event. Dramatic fundamental changes are required to neutralize such risks]

The next burden will fall on the creditors.

What concerns me though has been the contagion risk, as I wrote in September (bold original)[30]

While San Miguel looks like a fragile company highly sensitive to changing conditions, what matters for me is the risk of a contagion; particularly the companies, banks and entities whom are creditors to SMC’s 400+ billion loans.

While 400+ billion pesos seems like a drop in a bucket in a system flushed presently with 5.7 trillion pesos of liquidity, the domino effect from a potential SMC credit event may in a snap of finger—the bang moment—turn abundance into scarcity.

From San Miguel’s viewpoint we can note of the escalating systemic risks in the domestic financial system which puts into a tenuous spot claims that banks and financial institutions has made “very deliberate choices”

Behavioral Objections to the Shopping Mall Bubble

This leads us to the second systemic risk: the shopping mall bubble

In January of this year[31], I wrote a controversial article which seems to have upset what seems as an entrenched belief by the consensus. Particularly I pointed to the deepening imbalances between supply side growth along with demand side, the former having been funded by a credit boom.

Basically the objections I receive fall into two categories: sentiment and habit.

Sentiment.

The sentiment based objection has been to equate ‘crowd traffic’ with ‘revenues’. They essentially assume that what they see in malls in terms of throngs of crowd as equivalent to implied spending power.

Such objections essentially fall for psychological errors based on Sensory testing[32], particularly expectations error, the halo effect and logical error.

You see it is easier to make an observation and discern according to crowd traffic from within a mall in general than to add to the mental burden by going out and assess the crowd traffic in other malls and of malls under construction. Even from within the mall it is easier to assume general crowd traffic than to evaluate crowd traffic per store.

Expectations error is where people judge according to their previous or exiting knowledge. The Halo effect is when people judge according to their overall impression. Logical error is the error of association, particularly in the case of shopping malls where crowd equals revenues.

We have already seen how such errors played out when the consensus justified skyrocketing technology stocks with ‘eyeballs’ or where the number of page views or audience traffic was assumed as monetizing websites. The concept of eyeballs, in Wikipedia[33] definition, was popularized during the Dot com boom as an indicator of how much revenue potential a company would have for the future.

Psychologist, Nobel Prize winner and author Daniel Kahneman in his latest book observed of how people have been hardwired to think less[34]

A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs. Laziness is built deep into our nature.

We know in fait accompli how this turned out, boom morphed into bust. Reality exposed on the bubble outlook and laziness mentality.

Let us give the benefit of the doubt where ‘crowd traffic equals revenue’, if we consider the population growth rate of the Philippines (1.7% 2012) relative to conservatively shopping mall growth rate at 10% per annum, one would realize that the extensive growth in shopping mall supply will eventually reduce crowd traffic in shopping malls.

For instance let us assume that NCR has a population of 15m where 10 malls exists and where crowd traffic are dispersed evenly or 1.5 million per mall (ceteris paribus-all things held constant). Let us further assume that growth in malls double while population remains constant, this means for 20 malls crowd population will diminish to 750k per mall and so forth.

Of course hardly anything is constant. Growing supply relative to demand could mean marginal malls (new or less strategically located malls or malls with fewer regular patrons) will suffer most from diminished crowd traffic than from the established counterparts. Or an overall downsizing of crowd on each mall but on a relative scale could even be an outcome.

Crowd traffic equals revenues while seemingly plausible can hardly stand the rigors of basic math and common sense

Habit

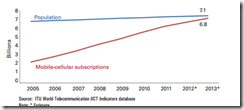

Twenty years ago, how many people in the world has mobile phones? The ITU mobile phone-population data shows how mobile phone subscriptions have closed the gap between population and mobile subscriptions[35] even from 8 years back.

And as testament to this penetration level of mobile phones relative to the Philippine population has reached 100% in 2012 according to reports[36].

The point here is that there is nothing constant but change.

Internet penetration has been spreading throughout the world and through Asia[37]. In the Philippines, internet connection has reportedly reached 36% penetration level[38].

Of course growing internet penetration levels are likely to deepen e-commerce.

In the US there is a new retail trend called as “showrooming” where showrooming is the practice of examining merchandise in a traditional brick and mortar retail store without purchasing it, but then shopping online to find a lower price for the same item[39].

In other words, showrooming combines the features of e-commerce with traditional physical retailing but more at the expense of the latter

My daughter is partly a practitioner of showrooming. What she sees in shopping malls she searches in the web, and according to her, when she finds the equivalent, goods are a lot cheaper from the internet. She cited me an example where she bought a bag that was 29% less than the list price at a domestic retail outlet net of shipping costs.

The “cheap” advantage of the web should come as natural. First e-commerce have been covered by lesser taxes. In the Philippines, the E-Commerce Law, R.A. No. 8792, according to Punong Bayan & Araullo[40] lacks specific provisions for the treatment of internet taxation in the Philippines.

Second and most importantly web based commerce requires reduced overhead costs via physical spaces.

This means that if the showrooming trend becomes the next fashion in retailing, retail outlets would likely be redesigned as showrooms that need lesser space for “phasing” or merchandise display and for inventories.

This will reduce demand for large brick and mortar retail spaces thereby putting pressure on real estate and shopping mall supply.

In short, e-commerce may cannibalize on brick and mortar retailing.

This is further proof that there is no such thing as habit especially in the face of technology changes.

Excessive Corporate Debt and Stagflation as Pricks to the Shopping Mall Bubble

Let us proceed to systemic risks

Can you identify what is wrong with the two graphics above?

There are essentially three variables here: namely sales (black bar), Finance or Debt (blue bar) and Earnings before taxes interest depreciation and amortization or EBITDA (orange bar).

I don’t even need to argue of an industry wide shopping mall bubble to reveal of the growing risks shown above.

Essentially these two companies have been borrowing far faster than the rate of growth of sales and EBITDA. The rapidly ascending derivative ratio which represents the leverage in terms of debt/ebitda has been evidence of this. The red rectangle represents projection for 2014 and 2015.

Even if we assume that the law of economics will be suspended, where both companies will see a sustained rise in sales and ebidta in perpetuity, at the rate of the borrowing binge, debt levels will eventually become a self-imposed burden that will impact on earnings and profitability, expansion of projects, put a kibosh on management flexibility and lastly increase credit risks.

This also means that eventually the companies may resort to SMC’s model of debt in and debt out.

If we factor in the demand-supply imbalance then like many highly leveraged firms they will become even more vulnerable to changes in interest rates (domestic and or foreign), foreign currency (for companies with foreign debt), inflation and competition.

Before I forget the above companies are SM Primeholdings[41] [PSE: SMPH], the largest mall operator in the Philippines and Filinvest Land[42] [PSE: FLI], one of the largest horizontal developers who also operate a mall: Filinvest Festival Mall in Alabang.

SMPH’s long term debt has ballooned by about 39% from Php 49.647 billion at the close of 2012 to Php 69.066 billion at the 3rd quarter’s close[43].

SMPH’s debt issuance has doubled through the third quarter of this year from the end of 2012

If the competition driven imbalance will reveal of what I expect then things will always move in the margins or from periphery to core.

For shopping malls, the “periphery to the core” would start from the mall areas with the least traffic and from marginal malls or arcades.

Surpluses amidst a boom which implies high rents, high cost of operations such as wages, electricity and other inputs prices, would place pressure on profits of retail tenants competing for consumers with limited purchasing capacity.

Periphery to the core would mean initially fast turnover from retail tenants on stalls of lesser traffic areas and of marginal malls. Then the length of vacancy extends and the number of vacancy spreads.

Leveraged malls and arcades thus will suffer from the same vicious cycle of cash flow problems and eventual insolvencies that will impair creditors and will spread to many sectors of the economy.

Additionally as I noted above the populist outrage over rising energy and fuel costs represents a threat to the highly touted Filipino consumer.

Rising prices of basic goods will extrapolate to a redistribution of consumer spending. This means that given that fuel light and transportation costs have been key factors in the household budget[45], add to this rising rents, and eventually food prices, a diversion of spending to basic goods means lesser disposable income and consequently demand.

Moreover, such factors will also impact retail outlets as rising input prices put a squeeze in profits which will be further aggravated by diminishing purchasing power of consumers.

Of course, not only the above, rising inflation expectations will translate to higher interest rates. If this should occur then the convergence trade will likely be exposed and unravel, thereby putting extra burden on highly leveraged companies or firms, as well as, increasing credit risks of the property related industries.

So rising CPI will likely have a trifecta impact on the shopping mall bubble via reduced consumer demand, squeezed earnings for retailers which should spillover to mall operators and to creditors, and that higher interest rates that are likely to increase credit risks of such industries.

All told, aside from excessive corporate debt and competition, stagflation could likely be another potential prick to the shopping mall bubble.

Again any slowing of demand will not only impact the retail and shopping mall industry but likewise all other property sector related businesses.

In the 1997 vacancy rates in Thailand hit 15% that sparked a regional crisis[46]. The Philippines then even had only 1%. This is not to suggest of a parameter threshold for a crisis, everything will depend on the prevailing conditions and the degree of confidence of creditors.

Nonetheless this is to say that the massive scaling up of debt on major industry players signifies in and on itself the escalating degree of risks, especially in the face of the global bond vigilantes.

Simply said, the prospects of reward look hardly appealing to override the growing scale of risks.