Deficits are always a

spending problem, because receipts are, by nature, cyclical and volatile, while

spending becomes untouchable and increased every year—Daniel Lacalle

In this issue

Debt-Financed Stimulus Forever? The Philippine Government’s Relentless Pursuit of "Upper Middle-Income" Status

I. Changes in Tax

Collection Schedules Distort Philippine Treasury Data and Highlight Fiscal Cycles;

Spending’s Legal Constraints

II. Stimulus Forever?

The Quest for "Upper Middle-Income" Status and Credit "A" Rating,

Rising Risks of a Fiscal Blowout

III. 10-Month Public Revenue

Growth Deviates from PSEi 30’s Activities

IV. Q3 2024: 2nd Highest

Revenue to NGDP, Headline GDP Weakens—The Crowding Out Effect?

V. Record 10-Month Expenditure:

The Push for "Big Government"

VI. 10-Month Debt Servicing

Costs Zoom to All-Time Highs!

VII. Rising Foreign Denominated

Debt Payments!

VIII. Despite Slower

Increases in Public Debt, Little Sign of the Government Weaning Off Stimulus

IX. Q3 2024: Public Debt

to GDP rises to 61.3%

X. Conclusion: The Relentless Pursuit Of "Upper Middle Income" Status Resembles a Futile Obsession

Debt-Financed Stimulus Forever? The Philippine Government’s Relentless Pursuit of "Upper Middle-Income" Status

Improvements in the 10-month fiscal balance have fueled the Philippine government’s unrealistic fixation on achieving 'Upper Middle Income' status—here's why.

I. Changes in Tax Collection Schedules Distort Philippine Treasury Data and Highlight Fiscal Cycles; Spending’s Legal Constraints

Inquirer.net, November 28: A double-digit revenue growth helped swing the government’s budget position back to a surplus in October, keeping the 10-month fiscal deficit below the 2024 ceiling set by the Marcos administration. The government ran a budget surplus of P6.3 billion in October, a reversal from the P34.4- billion deficit recorded a year ago, figures from the latest cash operations report of the Bureau of the Treasury (BTr) showed.

Most media outlets barely mention that recent changes in tax collection schedules have distorted the Bureau of the Treasury’s reporting data.

As noted in September, these adjustments significantly impact the perception of fiscal performance.

That is to say, since VAT payments are made at the end of each quarter but recorded in the first month of the following quarter, this quarterly revenue cycle inflates reported revenues for January, April, July and October, often resulting in a narrowed deficit or even a surplus for these months.

Therefore, we

should anticipate either a surplus or a narrower deficit this October.

(Prudent Investor, October 2024)

Figure 1

For instance, October’s surplus of Php 6.34 billion underscores how the quarterly revenue cycle boosts collections at the start of every quarter, often leading to either a surplus or a narrowed deficit. Surpluses were observed in January, April, and October this year. (Figure 1, topmost chart)

However, as the government pushes to meet its year-end 'budget execution' targets in December, a significant spike in the year-end deficit could emerge from the remaining spending balance.

Based on the budget allocation for 2024 amounting to Php 5.768 trillion, the unspent difference from the ten-month spending of Php 4.73 trillion is Php 1.038 trillion.

Notably, in contrast to previous years, 2024 has already experienced three months of public spending exceeding Php 500 billion, with December still underway. (Figure 1, middle image)

On the other hand, this could indicate a potential frontloading of funds to meet year-end targets.

While spending excesses are constrained by law, the government has consistently exceeded enacted budget allocations since 2019. (Figure 1, lowest diagram)

Consequently, this trend, shaped by political path dependency, suggests that the remaining Php 1.038 trillion could likely be surpassed.

According to the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), budget adjustments are permissible under specific conditions: (DBM, 2012)

1. Enactment of new

laws,

2. Adjustments to

macroeconomic parameters, and

3. Changes in resource availability.

These provisions may provide political rationales to justify increases in the allocated budget.

Figure 2

Expenditures, while down from last month, remain within their growth trajectory, while revenues have so far outperformed expectations. (Figure 2, topmost graph)

Despite October’s 22.6% revenue growth contributing to a lower ten-month deficit—down from Php 1.018 trillion in 2023 to Php 963.9 billion—it remains the fourth largest on record.

II. Stimulus Forever? The Quest for "Upper Middle-Income" Status and Credit "A" Rating, Rising Risks of a Fiscal Blowout

What is seldom mentioned by mainstream media is that such deficits serve as "fiscal or automatic stabilizers," ostensibly for contingent or emergency (recession) purposes.

While authorities repeatedly propagate their intent to elevate the economy to "upper middle-income" status and attain a credit "A" rating soon, they fail to disclose that current political-economic conditions are still functioning under or reflect continued reliance on a "stimulus" framework.

In fact, as we keep pointing out, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP)’s reserve requirement ratio (RRR) and interest rate cuts represent monetary measures, while authorities have ramped up fiscal measures or "Marcos-nomics stimulus" for their political agenda—namely, pre-election spending and a subtle shift toward a war economy, alongside centralization through increased public spending and an enlarged bureaucracy or "Big Government."

Finally, while expenditures adhere to programmed allocations and revenues fluctuate based on economic and financial conditions as well as administrative efforts, they remain inherently volatile.

Any steep economic slowdown or recession would likely compel the government to increase spending, potentially driving the deficit to record levels or beyond.

Unless deliberate efforts are made to curb spending growth, the government’s ongoing centralization of the economy will continue to escalate the risk of a fiscal blowout.

Despite the mainstream's Pollyannaish narrative, the current trajectory presents significant challenges to long-term fiscal stability.

III. 10-Month Public Revenue Growth Deviates from PSEi 30’s Activities

Let us now examine the details.

In October, public revenue surged by 22.6%, driven primarily by a 16.94% growth in tax revenues, with the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) contributing 16.19% and the Bureau of Customs (BOC) 11.5%. Meanwhile, non-tax revenues soared by 87.7%, largely due to revenues from other offices, including "privatization proceeds, fees and charges, and grants."

These activities boosted the 10-month revenue growth from 9.4% in 2023 to 16.8% this year, largely driven by a broad-based increase, largely powered by non-tax revenues.

It is worth noting that, despite reaching a record high in pesos, the BIR’s net income and profit growth significantly softened to 8.3%, the lowest since 2021, remaining consistent with the 9-month growth rate. This segment accounted for 50% of the BIR’s total intake. (Figure 2, middle pane)

In contrast, sales taxes jumped by 30.6% over the first 10 months, marking the highest growth rate since at least 2017, and represents 30% of the BIR’s total revenues. Sales taxes vaulted by 31.6% in the first 9 months. (Figure 2, lowest chart)

The reason for focusing on the 9-month performance is to compare its growth rate with that of the PSEi 30, allowing for a closer understanding or providing a closer approximation of the BIR's topline performance.

Figure 3

Unfortunately, when using same-year data, the PSEi 30 reported a 9-month revenue growth of 8.1%, the slowest since 2021. This pattern is echoed in its net income growth of 6.8%, which is also the most sluggish rate since 2021. (Figure 3 upper window)

To put this in perspective, as previously discussed, the 9-month aggregate revenues of the PSEi 30 represent approximately 27.9% of the nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) for the same period.

IV. Q3 2024: 2nd Highest Revenue to NGDP, Headline GDP Weakens—The Crowding Out Effect?

In its September disclosure, the Bureau of the Treasury cited changes in the VAT schedule as a key factor boosting tax collections: " The increase in VAT collections in 2024 is partly due to the impact of the change in payment schedule introduced by the TRAIN law provision which allows the tax filers to shift from monthly to quarterly filing of VAT return" (Bureau of Treasury, October 2024) [bold added]

Once again, the adjustment in VAT schedules played a pivotal role in increasing revenues, helping to reduce the deficit and debt—a topic we discussed in September 2024 (Prudent Investor, September 2024).

Or, whether by design or as an unintended consequence, a critical factor in the slower deficit has been a shift in government tax collection and accounting procedures.

But what will happen if, under the same economic conditions or with only slight improvements, the effects of such transient changes wear off? Will the deficit soar again?

Moreover, it is important to note that all this is occurring while bank credit expansion and public debt are at record highs.

What will happen to credit and liquidity-fueled demand once household and corporate balance sheets become saturated with leverage?

It’s also noteworthy that, even as the share of revenue to nominal GDP (NGDP) reached its highest level in Q2 and Q3 of 2024, real GDP continues its downward trend—a dynamic that has persisted since 2016 and reemerged in 2021. (Figure 3, below graph)

Are these not symptoms of the "crowding-out effect," where the increasing share of government interventions, measured by expenditures, debt, and deficits, translates into diminished savings and capital available for private sector investments?

V. Record 10-Month Expenditure: The Push for "Big Government"

But what about expenditures?

Local Government Unit (LGU) spending surged by 11.97%, and national disbursement growth reached 14.3%, powering an overall increase in October expenditures of 11.1%. Interest payments, on the other hand, fell by 6.1%. The former and the latter two accounted for shares of 18.1%, 66.64%, and 11.9% of the total, respectively.

For the first 10 months of the year, expenditures grew by 11.5%, reaching a record-high Php 4.73 trillion, driven by LGU spending, National disbursements, and interest payments, which posted growth rates of 9.1%, 11.9%, and 23.03%, respectively.

As noted above, these record expenditures are primarily focused on promoting political agendas: pre-elections, a subtle shift towards a war economy, and an emphasis on centralization through infrastructure, welfare, and bureaucratic outlays.

Figure 4

One notable item has played a considerable role: 10-month interest payments not only outperformed other components in terms of growth but also reached a record high in peso terms. (Figure 4, topmost graph)

Additionally, their share of total expenditures rose to levels last seen in 2009.

That said, the ratio of expenditures to NGDP remains at 23.98% in Q2 and Q3 and has stayed within the range of 22% to 26%—except for two occasions—since Q2 2020. (Figure 4, middle chart)

Over the past 18 quarters, this ratio has averaged 23.4%.

As mentioned above, despite all the hype about achieving "upper middle income" status and attaining a "Class A" credit rating, the Philippines continues to operate under a fiscal stimulus framework, which has only intensified with recent policies which I dubbed as "Marcos-nomics stimulus."

In the timeless words of the distinguished economist Milton Friedman, "Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program."

Current conditions also validate the "Big Government" theory articulated by the economist Robert Higgs, particularly regarding what he termed "The Ratchet Effect." This concept refers to the "tendency of governments to respond to crises by implementing new policies, regulations, and laws that significantly enhance their powers. These measures are typically presented as temporary solutions to address specific problems. However, in history, these measures often outlast their intended purpose and become a permanent part of the legal landscape." (Matulef, 2023)

The push towards "Big Government" is evident, with approximately a quarter of the statistical economy deriving from direct government expenditures.

This figure does not include the indirect contributions from private sector participation in government activities, such as public-private partnerships (PPPs), suppliers, outsourcing and etc.

As a caveat, the revenue and expenditure-to-NGDP ratio is derived from public revenue and spending data and nominal GDP—an aggregate measure where government spending is calculated differently—potentially leading to skewed interpretations of its relative size.

In any case, as the government grows, so too does its demand for resources and finances—all at the expense of the private sector, particularly micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), as well as the purchasing power of the average Filipinos, represented here as Pedros and Marias.

While government fiscal health may provide some insights into its size, there are numerous hidden or immeasurable costs associated with its expansion: compliance costs, public sector inefficiencies, regulatory and administrative burdens, policy uncertainty, moral hazard, opportunity costs, reduced incentives for innovation, deadweight losses, productivity costs, economic distortions, social and psychological costs, and more.

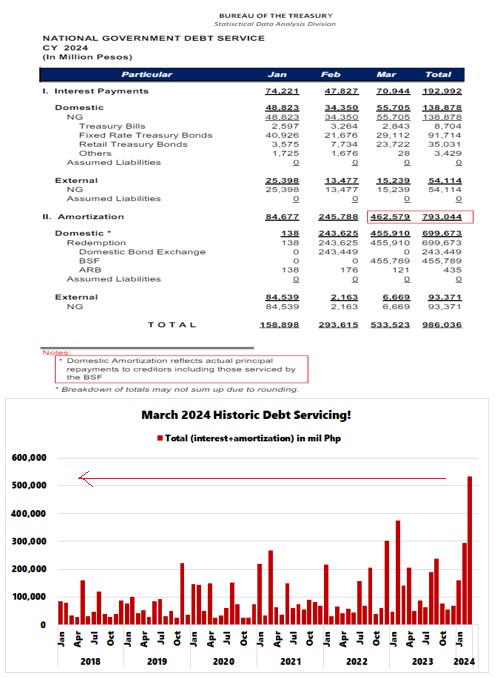

VI. 10-Month Debt Servicing Costs Zoom to All-Time Highs!

Rising interest payments represent some of the symptoms of "Big Government."

What’s remarkable is that, in just the first 10 months of 2024, the cost of servicing debt (amortization plus interest) soared to an all-time high of Php 1.86 trillion—16% higher than the previous annual record of Php 1.603 trillion set in 2023. And there are still two months to go! (Figure 4, lowest visual)

Amortization and interest payments exceeded their 2023 annual figures by 25.3% and 1.65%, respectively.

Notably, amortization payments surged by a staggering 760% in October alone, reaching Php 161.5 billion.

As a result, amortization and interest payments have already surpassed their full-year 2023 totals. However, because the government categorizes amortizations (or principal payments) as financing rather than expenditures, they are not included in the budget.

VII. Rising Foreign Denominated Debt Payments!

There's more to consider.

Figure 5

Payments (amortization + interest) on foreign-denominated debt in the first 10 months of 2024 increased by 52%, reaching a record high. This brought their share of total payments to 21.9%, the highest since 2021. (Figure 5, topmost chart)

Unsurprisingly, the government borrowed USD 2.5 billion in the end of August, likely to refinance existing obligations. Adding to this, authorities reportedly secured another $500 million loan from the Asian Development Bank last week in the name of "climate financing."

Nonetheless, these serve as circumstantial evidence of increased borrowing to fund gaps, reflecting the "synthetic dollar short" position discussed last week.

VIII. Despite Slower Increases in Public Debt, Little Sign of the Government Weaning Off Stimulus

Here’s where mainstream narratives often place emphasis: a slower deficit translates into slower growth in public debt. (Figure 5, middle graph)

In other words, a decrease in financing requirements or a reduction in the rate of increase in public debt decreases the debt/GDP ratio.

Authorities are scheduled to announce public debt data next week.

The apparent gaslighting of fiscal health suggests that authorities are employing tactical measures to improve macroeconomic indicators temporarily. These efforts seem aimed at buying time, likely in the hope that the economy will gain sufficient traction to mask structural weaknesses.

Still, while public debt continues to rise—albeit at a slower pace—bank financing of public debt through net claims on the central government (NCoCG), which began in 2015, appears to have temporarily plateaued. At the same time, the BSP's direct financing of the national government seems to have stalled. (Figure 5, lowest image)

However, none of these emergency measures have reverted to pre-pandemic levels.

The government shows no indication of weaning itself off the stimulus teats.

IX. Q3 2024: Public Debt to GDP rises to 61.3%

Unfortunately, the record savings-investment gap underscores a troubling reality: the GDP is increasingly propped up by debt.

While mainstream narratives highlight the prospect of a lower public debt-to-GDP ratio, they often fail to mention that public debt does not exist in isolation.

In the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis, the Philippine economy underwent a cleansing of its balance sheet, which had been marred by years of malinvestment. When the Great Financial Crisis struck in 2007-2008, the Philippine economy rebounded, aided by the national government’s automatic stabilizers and the BSP's easing measures.

However, during that period, the BSP mirrored the Federal Reserve's policy playbook, prompting the private sector to absorb much of the increased borrowing. This reduced the economy’s reliance on deficit-financed government spending and shifted the debt burden from the public to the private sector, enabling a decline in the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

Today, however, this is no longer the case.

Figure 6

Following the pandemic-induced recession, where bank credit expansion slowed, the government stepped in to take the reins, driving public debt-to-GDP to surge. As of Q3, it remained at 61.3%—the second highest level since 2021’s peak of 62.6% and the highest since 2004.

Currently, despite high-interest rate levels, both public borrowing and universal commercial bank lending have been in full swing—resulting in a systemic leverage ratio (public debt plus universal commercial bank credit) reaching 108.5% of nominal GDP in 2023.

This means that the government, large corporations, and many households with access to the banking system are increasingly buried in debt.

In any case, debt is perceived by consensus as a "free lunch," so you hardly ever hear them talk about it.

X. Conclusion: The Relentless Pursuit Of "Upper Middle Income" Status Resembles a Futile Obsession

In conclusion, while current fiscal metrics may appear to show surface-level improvements, the government remains addicted to various free-lunch policies characterized by easy money stimulus.

The government and elites will likely continue to push for a credit-driven savings-investment gap to propel GDP growth, leading to further increases in debt levels and necessitating constant liquidity infusions that heighten inflation risks.

The establishment tend to overlook the crowding-out effects stemming from government spending (and centralization of the economy), which contribute to embedding of the "twin deficits" that require more foreign financing—ultimately resulting in a structurally weaker economy.

The relentless pursuit of "upper middle income" status resembles a futile obsession—a "wet dream" driven more by the establishment’s obsession with benchmarks manifesting social signaling than substantive progress.

For distributional reasons (among many others), the GDP growth narrative does not reflect the true state of the economy.

Persistent self-rated poverty and hunger, widening inequality, elevated vacancies in the real estate sector, low savings rates, and stagnating productivity are clear indicators that GDP number benefits a select few at the expense of many. This, despite debt levels soaring to historic highs with no signs of slowing.

Even the Philippine Statistics Authority’s (PSA) per capita consumer and headline GDP trendlines contradict the notion of an imminent economic or credit rating upgrade.

While having the U.S. as a geopolitical ally could offer some support in the pursuit of cheaper credit through a potential credit upgrade, it is important to acknowledge that actions have consequences—meaning the era of political 'free lunches' are numbered.

And do authorities genuinely believe they can attain an economic upgrade through mere technical adjustments of tax schedules and dubious accounting practices, akin to the "afternoon delight" and 5-minute "pre-closing pumps" at the PSEi 30?

Yet because the political elites benefit from it, trends in motion tend to stay in motion, until…

___

References

Prudent Investor, September 2024 Fiscal Deficit Highlights the "Marcos-nomics Stimulus"; How Deficit Spending Drives a WEAKER Philippine Peso October 28, 2024

Department of Budget and Management, THE BUDGETING PROCESS, March 2012, dbm.gov.ph

Bureau of Treasury, September 2024 Budget Deficit at P273.3 Billion Nine-Month Deficit Narrowed to P970.2 Billion, October 24, 2024, treasury.gov.ph

Prudent Investor, Philippine Government’s July Deficit "Narrowed" from Changes in VAT Reporting Schedule, Raised USD 2.5 Billion Plus $500 Million Climate Financing, September 1, 2024

Michael Matulef Beyond Crisis: The Ratchet Effect and the Erosion of Liberty, August 18, 2023, Mises.org