2013 turned out to be a very interestingly volatile and surprising year. It was a year of marked by illusions and false hope.

Mainstream’s Aldous Huxley Syndrome

The Philippine Phisix appears to be playing out what I had expected: the business cycle, or the boom-bust cycle. Business cycles are highly sensitive to interest rate movements.

At the start of 2013 I wrote[1],

the direction of the Phisix and the Peso will ultimately be determined by the direction of domestic interest rates which will likewise reflect on global trends.

Global central banks have been tweaking the interest rate channel in order to subsidize the unsustainable record levels of government debts, recapitalize and bridge-finance the embattled and highly fragile banking industry, and subordinately, to rekindle a credit fueled boom.

Yet interest rates will ultimately be determined by market forces influenced from one or a combination of the following factors as I wrote one year back: the balance of demand and supply of credit, inflation expectations, perceptions of credit quality and of the scarcity or availability of capital.

The Philippine Phisix skyrocketed to new record highs during the first semester of the year only to see those gains vaporized by the year end.

During the first half of the year, I documented on how Philippine stocks has segued into the mania phase of the bubble cycle backed by parabolic rise by the Phisix index (for the first four months the local benchmark rose by over 5% each month!) and the feting or glorification of the inflationary boom via soaring prices of stocks and properties by the mainstream on a supposed miraculous “transformation[2]” of the Philippine economy backed by new paradigm hallelujahs such as the “Rising Star of Asia”[3], “We have the kind of economy that every country dreams of”[4], underpinned by credit rating upgrades, which behind the scenes were being inflated by a credit boom. This romanticization of inflationary boom is what George Soros calls in his ‘reflexivity theory’ as the stage of the flaw in perceptions and the climax[5].

While I discussed the possibility of a Phisix 10,000 as part of the inflationary boom process, all this depended on low interest rates.

But when US Federal Reserve chairman suddenly floated the idea of the ‘tapering’ or reduction of Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP) global equity markets shuddered as yields of US treasuries soared. Yields of US treasuries have already been creeping higher since July 2012 although the ‘taper talk’ accelerated such trend.

Since June 2013, ASEAN equity markets have struggled and diverged from developing markets as the latter went into a melt-up mode.

Just a week before the June meltdown I warned of the escalating risk environment due to the rising yields of Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) and US treasuries[6].

However, if the bond vigilantes continue to reassert their presence and spread, then this should put increasing pressure on risk assets around the world.

Essentially, the risk environment looks to be worsening. If interest rates continue with their uptrend then global bubbles may soon reach their maximum point of elasticity.

We are navigating in treacherous waters.

In early April precious metals and commodities felt the heat. Last week that role has been assumed by Japan’s financial markets. Which asset class or whose markets will be next?

Anyone from the mainstream has seen this?

Since the June meltdown, instead of examining their premises, the consensus has spent literally all their efforts relentlessly denying in media the existence of bear market which they see as an “anomaly” and from “irrational behavior”.

They continue to ‘shout’ statistics, as if activities of the past signify a guaranteed outcome of the future, and as if the statistical data they use are incontrovertible. They ignore what prices have been signaling.

My favorite iconoclast and polemicist Nassim Nicolas Taleb calls this mainstream devotion on statistical numbers as the ‘Soviet-Harvard delusion’ or the unscientific overestimation of the reach scientific knowledge.

He writes[7], (bold mine)

Our idea is to avoid interference with things we don’t understand. Well, some people are prone to the opposite. The fragilista belongs to that category of persons who are usually in suit and tie, often on Fridays; he faces your jokes with icy solemnity, and tends to develop back problems early in life from sitting at a desk, riding airplanes, and studying newspapers. He is often involved in a strange ritual, something commonly called “a meeting.” Now, in addition to these traits, he defaults to thinking that what he doesn’t see is not there, or what he does not understand does not exist. At the core, he tends to mistake the unknown for the nonexistent.

English writer Aldous Huxley once admonished “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” Thus I would call mainstream’s rabid denial of reality the Aldous Huxley syndrome

Mainstream pundits like to dismiss the massive increase in debt which had supported the current boom. They use superficial comparisons (as debt to GDP) to justify current debt levels. They don’t seem to understand that debt tolerance function like individual thumbprints and thus are unique. They treat statistical data with unquestioning reverence.

I’ll point out one government statistical data which I recently discovered as fundamentally impaired. What I question here is not the premise, but the representativeness of the data.

The Philippine Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) recently came out with 2012 Flow of Funds report noting that the households had been key provider of savings for the fifth year[8].

Going through the BSP’s “technical notes”[9] or the methodology for construction of the flow of funds for the households, the BSP uses deposits based on the banking sector, loans provided by life insurances, GSIS, SSS, Philippine Crop Insurance and Home Development Mutual Fund, Small Business Guarantee and Finance Corporation and National Home Mortgage and Finance Corporation. They also include “Net equity of households in life insurances reserves and in pension funds”, “Currency holdings of the household” and estimated accounts payable by households, as well as “entrepreneurial activities of households” and “other unaccounted transactions in the domestic economy”[10]

But the BSP in her annual report covering the same year says that only 21.5 households are ‘banked’[11]. Penetration level of life insurance, according to the Philam Life, accounts for only 1.1% of the population[12]. SSS membership is about 30 million[13] or only about a third of the population. GSIS has only 1.1 million members[14]. These select institutions comprise the meat of formal system’s savings institutions from which most of the BSP’s data have been based.

Yet even if we look at the capital markets, the numbers resonate on the small inclusion of participants—the Phisix has 525,085 accounts as of 2012[15] or less than 1% of the population even if we include bank based UITFs or mutual funds and a very minute bond markets composed mainly of publicly listed entities.

So no matter how you dissect these figures, the reality is that much of the savings by local households have been kept in jars, cans or bottles or the proverbial “stashed under one's mattress”.

In the same way, credit has mostly been provided via the shadow banking sector particularly through “loan sharks”, “paluwagan” or pooled money, “hulugan” instalment credit or personal credit[16].

In short, the BSP cherry picks on their data to support a tenuous claim.

In fairness, the BSP has been candid enough to say, at their footnotes, that the database for the non-financial private sector covers only “the Top 8000 corporations” and that for the “lack of necessary details” their “framework may have resulted to misclassification of some transactions”.

But who reads footnotes or even technical notes?

The Secret of the Philippine Credit Bubble

This selective data mining has very significant implications on economic interpretation and analysis.

This only means that many parts of the informal economy (labor, banking and financial system, remittances[17]) has been almost as large as or are even bigger than their formal counterparts.

We can therefore extrapolate that the statistical economy has not been accurately representative of the real economy.

Yet the mainstream has been obsessed with statistical data which covers only the formal economy.

And in theory, the still largely untapped domestic banking system and capital markets by most of the citizenry hardly represents a sign of real economic growth for one principal reason: The major role of banks and capital markets is to intermediate savings and channel them into investments. With lack of savings, there will be a paucity of investments and subsequently real economic growth.

In short, the dearth of participation by a large segment of the Philippine society on formal financial institutions represents a structural deficiency for the domestic political economy.

Any wonder why the mainstream pundits with their abstruse econometric models can’t capture or can’t explain why Philippine investments[18] have remained sluggish despite a supposed ‘transformational’ boom today?

This also puts to the limelight questionable efforts or policies by the government to generate growth via “domestic demand”.

Yet the mainstream hardly explains where “demand” emanates from? Demand may come from the following factors: productivity growth, foreign money, savings, borrowing and the BSP’s printing money.

With hardly significant savings to tap, and with foreign flows hobbled by rigid capital controls, the corollary—shortage of investments can hardly extrapolate to a meaningful productivity growth or real economic growth.

So in recognition of such shortcoming, the BSP has piggybacked on the global central bank trend in using low interest rates (then the Greenspan Put) to generate ‘aggregate demand’.

As a side note; to my experience, a foreign individual bank account holder can barely make a direct transfer from his/her peso savings account to a US dollar account and vice versa without manually converting peso to foreign exchange and vice versa due to BSP regulations.

The BSP anticipated this credit boom and consequently concocted a policy called the Special Deposit Accounts (SDA) in 2006, which has been aimed at siphoning liquidity[19]. Eventually the SDA backfired via financial losses on the BSP books even as the credit boom intensified.

The BSP imposed a partial unwinding of the SDA which today has only exacerbated the credit boom.

Given the insufficient level of participation by residents in the banking sector and the capital markets, thus the major beneficiaries and risks from the zero bound rate impelled domestic credit boom meant to generate statistical growth have been concentrated to a few bank account owners, whom has accessed the credit markets. This in particular is weighted on the supply side, e.g. San Miguel

The credit boom thus spurred a domestic stock market and property bubble.

This has been the secret recipe of the so –called transformational booming economy.

Yet, the large unbanked sector now suffers from the consequences of a credit boom—rising price inflation.

Well didn’t I predict in 2010 for this property bubble to occur?

Here is what wrote in September 2010[20]

The current “boom” phase will not be limited to the stock market but will likely spread across domestic assets.

This means that over the coming years, the domestic property sector will likewise experience euphoria.

For all of the reasons mentioned above, external and internal liquidity, policy divergences between domestic and global economies, policy traction amplified by savings, suppressed real interest rate, the dearth of systemic leverage, the unimpaired banking system and underdeveloped markets—could underpin such dynamics.

My point is that these bubbles have been a product of the policy induced business cycle.

Also these can hardly represent real economic growth without structural improvements in the financial system via a financial deepening or increased participation by the population in the banking sector and in the capital markets.

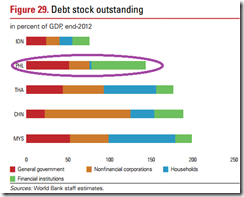

The chart from a recent World Bank report[21] represents a wonderful depiction of the distinctiveness of the distribution credit risks of ASEAN and China.

From the Philippine perspective, households indeed have very small debt exposure basically because of low penetration levels in the Philippine financial system. Whereas most of the insidious and covert debt build up has been in the financial, nonfinancial corporations and the government.

Ironically, Indonesia whom has very low debt levels has been one of the focal point of today’s financial market stresses which I discuss in details below.

This only shows that there are many complex variables that can serve as trigger/s to a potential credit event. Debt level is just one of them.

Why a Possible Black Swan Event in 2014?

I say that I expect a black swan event to occur that will affect the Phisix-ASEAN and perhaps or most likely the world markets and economies.

The black swan theory as conceived by Mr. Taleb has been founded on the idea that a low probability or an ‘outlier’ event largely unexpected by the public which ‘carries an extreme impact’ from which people “concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact”[22]

The Turkey Problem signifies the simplified narrative of the black swan theory[23].

A Turkey is bought by the butcher who is fed and pampered from day 1 to day 1000. The Turkey gains weight through the feeding and nurturing process as time goes by.

From the Turkey’s point of view, the good days will be an everlasting thing. From the mainstream’s point of view “Every day” writes Mr. Taleb “confirms to its staff of analysts that Butchers love turkeys “with increased statistical confidence.””[24]

However, to the surprise of the Turkey on the 1,001th day or during Thanksgiving Day, the days of glory end: the Turkey ends up on the dinner table.

For the Turkey and the clueless mainstream, this serves as a black swan event, but not for the Butcher.

For me, the role of the butcher will be played by rising interest rates amidst soaring record debt levels.

Global public and private sector debt from both advanced economies and emerging has reached $223 trillion or 313% of the world’s gdp as of the end of 2012[25]. This must be far bigger today given the string of record borrowings in the capital markets for 2013, especially in the US (see below).

Moreover, recent reports say that there will be about $7.43 trillion of sovereign debt from developed economies and from the BRICs that will need to be refinanced in 2014. Such ‘refinancing needs’ account for about 10% of the global economy which comes amidst rising bond yields or interest rates[26].

While I believe that the latest Fed tapering has most likely been symbolical as the outgoing Fed Chair’s Ben Bernanke may desire to leave a legacy of initiating ‘exit strategy’ by tapering[27], the substantially narrowing trade and budget deficits and the deepening exposure by the Fed on US treasuries (the FED now holds 33.18% of all Ten Year Equivalents according to the Zero Hedge[28]) may compel the FED to do even more ‘tapering’.

Such in essence may drain more liquidity from global financial system thereby magnifying the current landscape’s sensitivity to the risks of a major credit event.

And unlike 2009-2011 where monetary easing spiked commodities, bonds, stocks of advanced and emerging markets, today we seem to be witnessing a narrowing breadth of advancing financial securities. Only stock markets of developed economies and of the Europe’s crisis afflicted PIGS and a few frontier economies appear to be rising in face of slumping commodities, sovereign debt, BRICs and many major emerging markets equities. This narrowing of breadth appears to be a periphery-to-core dynamic inherent in a bubble cycle thus could be seen as a topping process.

Meanwhile the Turkey’s role will be played by momentum or yield chasers, punters and speculators egged by the mainstream worshippers of bubbles and political propagandists who will continue to ignore and dismiss present risks and advocate for more catching of falling knives for emerging markets securities.

And the melt-up phase of developed economy stock markets will be interpreted by mainstream cheerleaders with “increased statistical confidence”.

The potential trigger for a black swan event for 2014 may come from various sources, in no pecking order; China, ASEAN, the US, EU (France and the PIGs), Japan and other emerging markets (India, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa). Possibly a trigger will enough to provoke a domino effect.

I will not be discussing all of them here due to time constraints

Bottom line: the sustained and or increasing presence of the bond vigilantes will serve as key to the appearance or non-appearance of a Black Swan event in 2014.

As a side note: the dramatic fall on yields of US Treasuries last Friday due to lower than expected jobs, may buy some time and space or give breathing space for embattled markets. But I am in doubt if this US bond market rally will last.

[update: I adjusted for the font size]

[24] Nassim Nicolas Taleb Op. cit p93